Phase Noise in Microwave Oscillators and Amplifiers

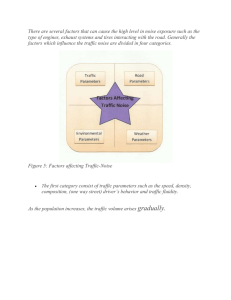

advertisement