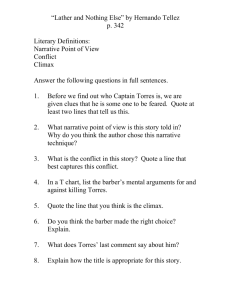

Joaquín Torres-García

advertisement