Developing an Understanding of How College Students Experience

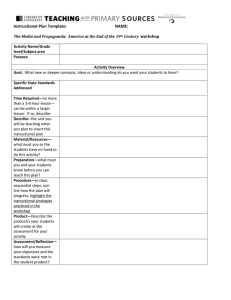

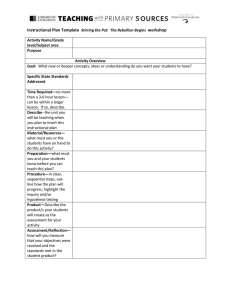

advertisement