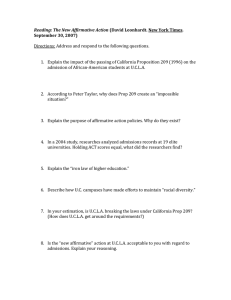

Have We Reached Grutter`s "Logical End Point?"

advertisement