tying funding to community college outcomes

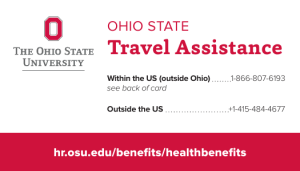

advertisement