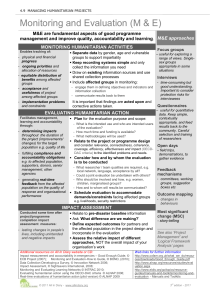

performance and effectiveness in the humanitarian sector

advertisement