Effects of the 1982-83 el Nino Event on Blue

advertisement

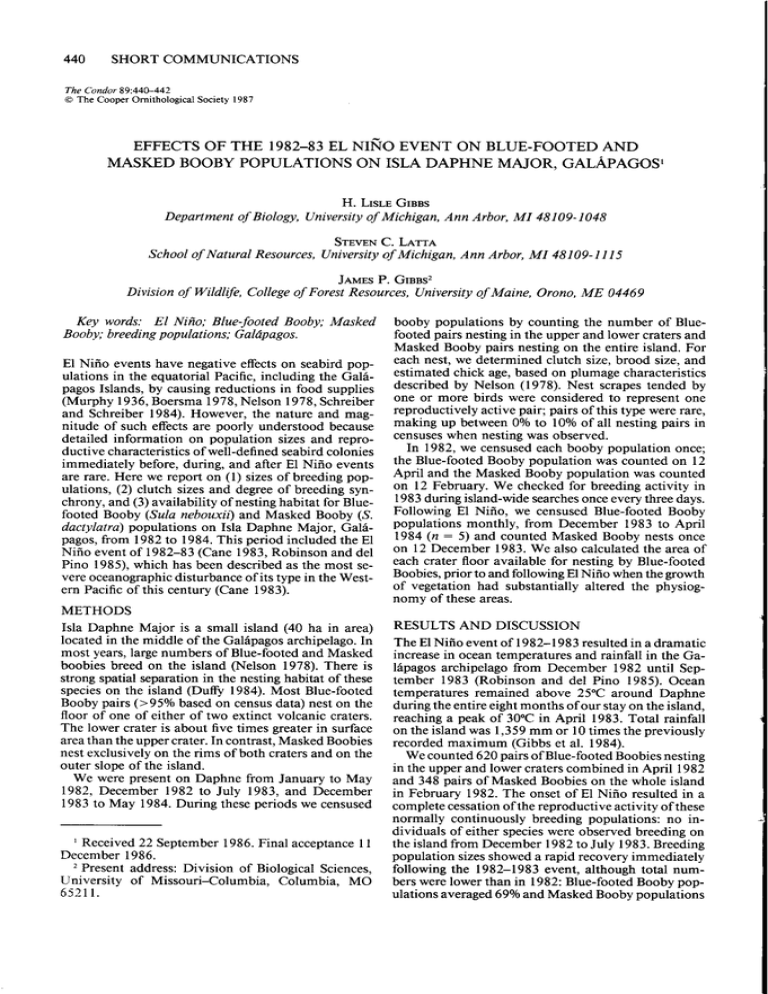

440 SHORT COMMUNICATIONS The Condor 89:440-442 0 The CooperOrnithologicalSociety1987 EFFECTS OF THE 198243 EL NIAO EVENT ON BLUE-FOOTED AND MASKED BOOBY POPULATIONS ON ISLA DAPHNE MAJOR, GAL&‘AGOS H. LISLE GIBBS Department of Biology, Universityof Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1048 STEVEN C. LATTA Schoolof Natural Resources,Universityof Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109- 1I1 5 JAMES P. GIBBS~ Division of Wildlife, Collegeof Forest Resources,Universityof Maine, Orono, ME 04469 Key words: El Niiio; Blue-footedBooby; Masked Booby;breedingpopulations:GalrIpagos. booby populations by counting the number of Bluefooted pairs nestingin the upper and lower cratersand Masked Booby pairs nesting on the entire island. For El Niiio events have negative effects on seabird pop- each nest, we determined clutch size, brood size, and estimated chick age, basedon plumage characteristics ulations in the equatorial Pacific, including the Gal& pagosIslands, by causingreductions in food supplies described by Nelson (1978). Nest scrapestended by (Murphy 1936, Boersma 1978, Nelson 1978, Schreiber one or more birds were considered to represent one and Schreiber 1984). However, the nature and mag- reproductivelyactive pair; pairs of this type were rare, nitude of such effects are poorly understood because making up between 0% to 10% of all nesting pairs in detailed information on population sizes and repro- censuseswhen nesting was observed. In 1982, we censusedeach booby population once; ductive characteristicsof well-defined seabirdcolonies immediately before, during, and after El Nifio events the Blue-footed Booby population was counted on 12 are rare. Here we report on (1) sizes of breeding pop- April and the Masked Booby population was counted ulations, (2) clutch sizes and degree of breeding syn- on 12 February. We checked for breeding activity in 1983 duringisland-widesearchesonceevery three days. chrony, and (3) availability of nestinghabitat for Bluefooted Booby (Sula nebouxii)and Masked Booby (S. Following El Nifio, we censusedBlue-footed Booby populations monthly, from December 1983 to April dactylatra) populations on Isia Daphne Major, caia1984 (n = 5) and counted Masked Booby nests once nagos.from 1982 to 1984. This Deriod included the El Ni?~oevent of 1982-83 (Cane 19‘83, Robinson and de1 on 12 December 1983. We also calculatedthe area of Pino 1985), which has been describedas the most se- each crater floor available for nesting by Blue-footed vere oceanographicdisturbanceof its type in the West- Boobies,prior to and followingEl Nifio when the growth of vegetation had substantially altered the physiogem Pacific of this century (Cane 1983). nomy of these areas. METHODS Isla Daphne Major is a small island (40 ha in area) RESULTS AND DISCUSSION located in the middle of the Galapagosarchipelago.In The El Niiio event of 1982-l 983 resultedin a dramatic most years,large numbers of Blue-footed and Masked increasein ocean temperaturesand rainfall in the Gaboobies breed on the island (Nelson 1978). There is lspagos archipelago from December 1982 until Sepstrongspatialseparationin the nestinghabitat of these tember 1983 (Robinson and de1 Pino 1985). Ocean specieson the island (D&y 1984). Most Blue-footed temperatures iemained above 25°C around’Daphne Booby pairs (>95% basedon censusdata) nest on the duringthe entire eight months of our stayon the island, floor of one of either of two extinct volcanic craters. reaching.a neak of 30°C in April 1983. Total rainfall The lower crater is about five times greater in surface on the iilanh was 1,359 mm 0; 10 times the previously areathan the uppercrater. In contrast,Masked Boobies recorded maximum (Gibbs et al. 1984). nest exclusivelyon the rims of both cratersand on the We counted620 pairsof Blue-footedBoobiesnesting outer slope of the island. in the upper and lower craterscombined in April 1982 We were present on Daphne from January to May and 348 pairs of Masked Boobies on the whole island 1982, December 1982 to July 1983, and December in February 1982. The onset of El Nifio resulted in a 1983 to May 1984. During these periods we censused completecessationof the reproductiveactivity of these normally continuously breeding populations: no individuals of either specieswere observed breeding on I Received 22 September 1986. Final acceptance11 the island from December 1982 to July 1983. Breeding December 1986. population sizesshoweda rapid recovery immediately * Present address:Division of Biological Sciences, following the 1982-1983 event, although total numUniversity of Missouri-Columbia, Columbia, MO bers were lower than in 1982: Blue-footed Booby pop65211. ulationsaveraged69% and Masked Booby populations . ; SHORT COMMUNICATIONS 441 TABLE 1. Numbers of Blue-footed and Masked booby pairs on Isla Daphne before, after, and during the 198283 El Nifio event. Periodof observation BeforeEl Niiio: Februaryand April 1982 Pairs of Blue-footed Boobies1 Pairs of Masked Boobies2 DuringEl Nifio: December 1982 to Julv1983 620 348 AfterEl Nifio: December 1983 to Mav 1984 425 f 663 135 ’ Numberof pairsin theupperandlowercrater i Numberof pairsontheentireisland. ’ Mean+ SE. 39% of pre-Niiio levels in late 1983 and early 1984 (Table 1). Clutch sizes of both booby specieswere smaller in post-Niiio populations. We estimated frequencies of different clutch sizes for Blue-footed Boobies in 1984 by combiningdata from December,February,and April censusesto avoid recounting the same nests in consecutivemonths. A significantlygreater proportion of Blue-footedBoobyne& had large; clutch sizesin 1982 (clutch size 1%total nestsl: 1 117%1:2 175%1:3 18%1: i = 446 total nests) than-in 1984 il [40%];?! [60%]: n = 110;G = 22.9, df= 2, P < 0.001). Masked Boobies showed a similar pattern. In both years, all clutches consistedof one or two eggs.In 1982, 53% of all nests had two eggs(n = 36 total nests)while only 27% had clutchesof two in 1984 (n = 34: G = 5.1. df = 1. P = 0.024). Clutch sizes may have been smaller in ‘1984 becausea Nifio-induced changein the age structureof both populations resulted in more young, inexperiencedbirds breedingin 1984 or becausefood supplies remained low following the 1982-1983 event. The degreeof breedingsynchronywassimilar in preand post-Nifio populations of both speciesalthough most pairs were at different stagesof the breedingcycle when censuseswere made in 1982 and 1984. For example, in April 1982 77% of all Blue-footed Booby pairs had eggswhile in December 1983, 85% of all pairs had chicks six weeks old or younger. Masked Boobies showed a similar pattern of synchrony: 64% had eight- to 12-week-oldyoungin February 1982while 67% had chickssix weeksold or voungerin December 1984. Therefore, becausea high-degreeof synchrony alreadyexistsin normal populations,the uniform onset of breeding following a Nifio event may not increase synchronyfurther. The increasein vegetative cover following El Nifio had a demonstrable effect on the availability of nest sitesto Blue-footed Boobiesin the large crater. Due to the heavy, sustainedrainfall during 1982-1983, a large proportion of the lower crater floor was covered in thick vegetation from July 1983 onwards. This vegetation covered 3,595 m2or 46% ofthe crater floor used by nesting boobies in 1982 and consisted mainly of annual plant speciesincluding Cacabusmiersii, Heliotropium angiospermum, Merremia aegyptica, Ipomoea linearfolia, and Chamaesyce amplexicaulis. Plants, previouslyabsent,also grew on the floor of the upper crater; however, they were sparselydistributed and did not decreasethe availability of nest sites. The differencein cover between the cratersprovided a natural experiment with which to examine the effect of the growth of vegetation on breeding populations of Blue-footed Boobies.In the upper crater, the numbers of nesting pairs, hence bird density, were remarkably similar in the two years (1982: 104 pairs; 0.061 pairs per m*; 1984: 101.5 pairs i 7.2 [mean + SE]; 0.063 pairs per m*). In the lower crater, there were fewer breedingpairs in 1984 than in 1982 (1982: 5 16 pairs; 1984: 323.3 ? 22.9) but the density of pairs in the nonvegetatedarea of the crater floor remained almost constant(1982: 0.062 nairs ner mZ: 1984: 0.069 uairs per m2).Thus, the reductionin the breedingpopulation of Blue-footed Boobiesin 1984 was apparently due to nest site limitation causedby changesin the cover of terrestrial vegetation during the 1982-83 El Nifio. Although quantitative data on changesin nest site availability are lackingfor Masked Booby populations, the dramatic increasesin vegetativecover on the outer slope of the island (Gibbs and Grant, unpubl.) may also account for the post-Niiio reduction in breeding populationsof this species.In 1984, Masked Boobies were not seennesting in newly-vegetatedareas,where they had previously bred in 1982 (H. L. Gibbs, pers. observ.). In conclusion,the 1982-1983 event had important short-term effects (cessationof breeding) and potentially long-term effects (smaller clutch sizes and reduced availability of nestinghabitat) on booby populations nesting on Daphne. Interruptions in breeding activity have also been reported for other Galapagos seabirdsduring this (Valle 1985) and other (Boersma 1978) El Nifio events. The vegetationin the lower crater has continued to limit thenesting habitat available to Blue-footedBoobiesun to Januarv1986(H. L. Gibbs, pers. observ.). Further studiesshould considerthe im: portance of such long-term indirect effectsof El Nifio on seabird populations nesting in arid regions of the equatorial Pacific. We thank Malcolm Coulter, Anne Wilson Goldizen, and Peter Grant for commentson the paper.This work wascarried out in conjunctionwith P. R. Grant’s studies of Galapagosfinches;we thank him for his assistance. Permissionto do this researchwas given by the GalapagosNational Park Service.The CharlesDarwin ResearchStation provided logistical support. LITERATURE CITED BOERSMA,P. D. 1978. Breedingpatternsof Galapagos Penguins as an indicator of oceanographicconditions. Science200:1489-1493. 442 SHORT COMMUNICATIONS CANE,M. 1983. OceanographiceventsduringEl Niiio. Science222:1189-l 195. Durrv, D. C. 1984. Nest site selection by Masked and Blue-footed boobies on Isla Espanola, Galapagos.Condor 86:301-304. GIBBS, H. L., P. R. GRANT, AND J. WEILAND. 1984. Breedingof Darwin’s finchesat an unusuallyearly age in an El Niiio year. Auk 101:872-874. Muar&, E. C. 1936. -Oceanic birds of South America. American Museum of Natural History, New York. NELSON, J. B. 1978. The Sulidae.Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford. ROBINSON, G., AND E. M. DELPINO. 1985. El Niiio The Condor 89:442-443 0 ne Cooper Ornithological in the Galapagos:the 1982-83 event. CharlesDarwin Foundation, Quito, Ecuador. SCHREIBER, R. W.. AND E. A. SCHREIBER.1984. Central Pacific seabirdsand the El Niflo SouthernOscillation: 1982 to 1983 perspectives.Science225: 713-716. VALLE,C. A. 1985. Alteracibn de las poblacionesde1 cormoran no volador, el pinguino y otras aves marinasen Galapagospor efectode El Niiio 198283 y su subsecuenterecuperation, p. 245-257. In G. Robinson and E. M.-de1 Pino [eds.], El Niiio in the Galapagos:the 1982-83 event. CharlesDarwin Foundation, Quito, Ecuador. Society 1987 CANNIBALISM IN AMERICAN COOTS INDUCED BY SEVERE SPRING WEATHER AND AVIAN CHOLERA’ DAVID G. PAULLIN U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service,MaNzeurNational Wildlife Refuge,P.O. Box 245, Princeton,OR 97721 Key words: American Coot;Fulica americana;cannibalism;feeding behavior;avian cholera;Pasteurella multocida. The food habitsofAmerican Coots(Fulica americana) havebeenwell documented(Jones1940;Stollberg1949; Eley and Harris 1976, Ivey 1987). These studieshave shown that plant food is the primary component of American Coot diets, althoughinvertebratesare commonly taken. However, coots may occasionally attempt to eat larger vertebrates(McCurdy 1983). Bent (1926) reported that coots have been known to pluck and partially eat dead ducks. Cannibalism includesboth the killing and eating or scavengingof conspecificsand in birds is most commonly reportedamong raptors,where younger,weaker nestlingsare sometimeskilled and eaten by siblingsor parents to reduce fratricidal strife (Newton 1979). I know of no recordsof cannibalismin American Coots, although, Cawston (1983) reported it for the closely related Common Moorhen (Gallinula chloropus). On 21 February 1984 at 14:37 I observedtwo American Coots eating a fresh carcasson ice adjacent to a small open water area on Malheur National Wildlife Refuge (NWR), Hamey County, Oregon. Closer examination (from a distance of approximately 25 m) 1Received 15 October 1985. Final acceptance 19 November 1986. revealedthe carcasswas a fresh coot. The sternum and ribs were completely exposedand most of the pectoral muscle tissue had been removed. The causeof death was unknown but sincethe carcasswasbeneatha powerline it was assumedthat death had resulted from a collisionwith the overheadwires. The two feedingcoots were immediately joined by four others, and the six beganvigorouslytearingand consumingthe remaining muscletissueand viscera. I returned to the site within 1 hr to continue observations;however, strong winds had broken the ice and the carcasshad sunk.The feeding coots had dispersed. By 22 February the number of dead coots had increased to seven and by 23 February there were 15 dead coots, all near the powerline. I observedno cannibalistic behavior on 22 February but on 23 February I observedtwo cootsseparatelyfeeding on two mostly intact coot carcasses.Throughout Februaryand March American Coots continued to die in the few areas of open water. I observedAmerican Coots cannibalizing coot carcasseson five occasionsduring this period. By late February it was apparent that not all dead coots could be attributed to powerline collisions because of the widening distribution of carcassesaway from the powerline. On 11 March five fresh coot carcasseswere collectedand sent to the National Wildlife Health Laboratory in Madison, Wisconsin for necropsy. All five birds were diagnosedas dvinn from avian cholera (Pasteurella mult&ida). Before the epizootic subsidedfollowing ice breakupin late March, 3 17 dead cootswere picked up and disposedof. Sixty additional