THE GOOGLE BOOK SETTLEMENT AS COPYRIGHT REFORM

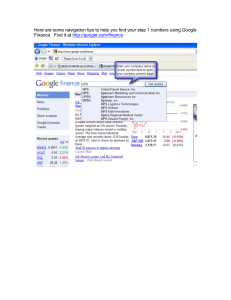

advertisement