A COMPILATION OF THE CANADIAN COPYRIGHT CASES

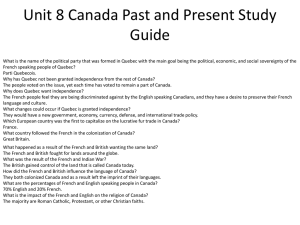

advertisement