young me. nightingale.

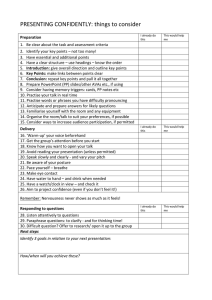

advertisement

STOIQ^QE • Qll£V:.ireES -.f^pll-Yl^^E^ " ^ ^

CONDUCTED-BY

s

WITH WHICH IS llsiCOi\POf^TED

.^ JIo JSEHOLD'VOHDS " ^

• r

—m

all

^ ^ > — • « • . .

in«

M i-^

SATURDAY, JUNE 7, 1873.

YOUNG ME. NIGHTINGALE.

• X THB AVTHOB OF "BOBSOM'S CUOICI," ftC.

•

CHAPTER VIII. MR. BTGRAVE.

PuREiNGTON Opinion was unfavourable to

the plan that had been adopted for my

education. I t was viewed as absurd and

even somewhat presumptuous. I t was certainly nnprecedented. " What be neighbour Orme thinking about ?" Mr. Jobling,

of the Home Farm, had been heard to

inquire. " Is he going to make a passon

of his nevvy ? Where be tho good of

hiring Passon Bygrave to stuff" his head

gilt Jut

wi* lAtton and Greek and such like ? He'll

ruin the boy. Bettor by half teke and

ailBs send un out to scare the craws or learn to do

snmmut useful. No good won't come on't.

I'd learned to plough a straight furrow, and

Tii)lit>> to handle a prong like e'er a man on my

&rm, long avore I was his age. Besides,

• o n ' * lirho wants a passon coming in and out of

a farm-house day arter day, like an old

woman ? It's quito ridic'lous. I'm surprised at neighbour Orme. But, there, 'tis

no use telking aboot it, I suppose. He

seems main bent on it. But I'm none so

terrible fond of passons myself; except on

Sundays of course."

Sentiments of this kind were so generally

if pan?

expressed that I could not help hearing

them. And I, too, Avas inclined to think

that the education Mr. Bygrave Avas engaged to impart was in the nature of a

vain and valueless thing. Why should I

be teught so much moro than my neighof,!

\ \ bours? It seemed to me rather foolish,

lore

and, what was even worse, feminine, to be

instructed in accomplishmente they had

never felt the lack of. It was like learning

to sew or to hem; useful arts in their Avay,

no doubt, but uuAA'orthy of a male creaturo's

VOU X.

acquiring. Happily, Mr. Bygrave did his

duty, so far as he could, as my instructor.

To the young child education is much as

medicine; even if he believe in the draught's

power to benefit him, yet he knows that ite

teste is disagreeable. Or if he begius to

quaff" it eagerly, his appetite soon fails. He

does not yet appreciato the pleasures of

duty; wisdom is weariness, and ignorance

still blissful to him. He finds it hard to

love the preceptor, who plucks him from

idle delighte, tethers him to school-books,

and expects him to enjoy the change,

I fear I did not do Mr, By grave justice.

Decidedly I did not love him. There Avas,

indeed, a certein lack of sympathy between

us. He was not, I think, intentionally unkind or Impatient, but he was unable to

teke account of my childishness. He seemed

to fancy that my small weak legs could keep

pace with his long strides, as we trod together the highways of wisdom. He knew

so much himself that he could not credit

the Ignorance of others. He often texed

me with trying to be stupid, AvhIch certainly Avould have been a supererogatory

effort on my part. And my boyish inability

to value duly the treasures of classical literature, ho estimated as somethiug amazing

in ite grossness and inanity.

If the authors of the remote past Avere

to me but unappetising food, they Avere as

meat and drink to Mr. Bygrave. The very

thought of them always seemed to bring

him new support and enjoyment. Ho

lingered fondly over long quotations from

them, smacking his lips after his utterances,

as though the flavour of fiue old wine bad

rejoiced his palate. He could deliver prodigious speeches from Greek plays, as easily

as I could pour out beer. He Avas, indeed.

In love Avith the dead, and especially with

the dead languages, and appeared to havo

^30

\

N>.

122

(JuneT. iBTD.]

ALL THE YEAR ROUND.

no heart or hope for the living Avorld of

lo-day. I remember the jilmust painful

a-stonishnunl it occaaioned ine w h e n l o n c e ,

by mere chance, discovered tliat he—so wise

a ni.ui—had neA-er reiid the Vicar of Wakefield, and was entirely nninfiirnied as to the

Avorks of Smollett. H e ])Iainly intimated

thathedes])i.'-ed such ^iroductions. I t often

c'»c<'ni!('d to Die, after thi.<, that Mr. Bygravi- had been b o m some two thousand

years too lale. How ho would have enjoyed, I thought, the .society of the ancient

]»oets and hist^riiins ! As to the opinion

they would haA'e entertained of hira I could

neA'cr quite make up my mind. I decided,

however, that he Avould not have looked

Avell in a toga.

H e Avas a tall, gaunt, long-necked,

j.:;no\v-cliested man, AAiih round shoulders,

: nd thin, unstable legs. H e had a habit

( f yawning frequently, stretching his limbs

until his muscles cracked noisily like dry

1 ranches in a gale of wind, and opening

Avide his large mouth to close it again Avitli

." crash. H e Avore always a hungry look,

iMS(miuch that my mother Avas wont to insist

that he suflx'rcd from insufficiency of food,

."ud invariably provided hiiU witb substential refreshment on bis A'isits to the Down

Farm Hou.se. His health did not appear

to be infirm, although his complexion Avas

jiallid and his frame attenuated ; he had a

loud harsh voice and a barking method of

s]>eech. I often likened myself to one of

Reube's lambs driven Into classical folds or

]iastures by the barking of my tutor—acting as a sheep-dog for the occasion.

Mr. Bygrave Avas respected at Purrington. because, time out of mind, it had been

t he Avay at Purrington to respect the clergy.

It Avas true that he only filled our pulpit

and reading-desk in consequence of the

extreme incapacity of our rector, old Mr.

Gascoigne; and that he did not reside at

the parsonage, but occupied apartments

f'A'cr the wheelwright's, " up-street," Purrington—it being, by the way, a firm conviction of my mother's that the wheelwright's

ju'emises Avere quite nuAvorthy of Mr. By*: i-ave's tenancy, and that Mrs. Munday, the

"^vheelAvright's Avife, in the way of providing

and cooking for a gentleman, and generally

iu looking after his comfort, was but " a

poor creature." Still, by reason of his

ofliciating in ^Ir. Gascoigne's place, and of

his biing in his own right a clergyman,

3fr. Byurave was generally viewed with

def'ror.ce and regard throughout the parish;

it being always understood, however, that

he was not to be likened to the rector,

P^

[CoadwHil^

but was .•ilto^rether a priest of inferior laoh;

if not, indeed, of a distinct species. l a h b

y(7«ngerd»ys M r . Ga.scoignc hadbeeanolid

fbr his skill in field-sports, and I n u d ai a

huntsman and a shot. Ho farmed kisomi

glebe, and bis boAA'ling waa a tiling qf!

Avhich elderly ciicketers of t h e Purriaglaji

Club—an institution he had originiSed^f

and for some time mainly supported—fH

spoke Avith enthusiasm. Mr. Bygrave

wholly without gifts of this k i n d ; he '

nothing of farming; he could neither ride

nor shoot; and although ho had upon nquest kept the score during the aanmL

cricket mateh between Purrington amb'

Bulborough, be bad not been intmstedi

with tbat office a second t i m e ; his in-,

efficiency was too glaring. That he

competent, howeA^er, to perform

pensable clerical duties in the way

marrying, christening, and burying

parishioners, could not be disputed; nor]

Avas much fault found with the sermons hel

Avas accustomed to deliver on Sunday afte^

noons thi'oughout the year.

Purrington

did not criticise sermons ; viewing them as

Avliolesome performances which were rather

to be endured, like surgical operations,

than enjoyed, or indeed understood. It

was thought, hoAvcA'er, that they did good

upon t h e whole; although this estimation'

of them regarded them somewhat in the

light of the incantetions of a wizard of

good character. I t m u s t be said that Mr.

Bygrave's discourses were not perhaps veiy

well calcolated for a rural congregatioB.

One special effort of his, however, in the

course of which he ventured upon certain

Hebrew quotations of considerable length,

won particular favour from his andittaf.'

I t was freely observed in the churchyai^

after service t h a t Mr. Battersby, the vicar

of Bulborough, the adjoining parish, conld

never have come u p to t h a t achievement

And that Mr. Bygrave, although a much

younger man, possessed " a zight more

learning."

Mr. Bygrave's position was not perhi

a very happy one. H i s means were

limited, and he was wholly without aiqi*'

thing like congenial companionship. Insnfl^i

society as P u r r i n g t o n could furnish, he

certainly not seen to advantege. Not thl^

he was shy or apparently ill at ease; buth#

was without power of speech upon mattaf

that did not Interest him, and was unabll

to sympathise, or to affect sympathy withthf

subjects that formed thesteple of PurringtflU

converse. W h a t were to him the conditiai

of the crops, the prices of barley, of sheep, or

H I HCbaries Dickens.]

YOUNG MR. NIGHTINGALE.

of wool ? Even the state of the weather was

as nothing to him. H e never seemed to

know if the sun were shining or not, the

wind blowing, or t h e rain falling. I had

seen him on most bitter days, leisurely

crossing the down, studying as he went

the pocket Horace he always carried with

him. Yet he was not perhaps to be pitied.

H e was happy after his own way.

His

studies were veiy dear to him, if they

Iwought little tangible profit to him or to

any one else. And he performed his duty

&.irly to the parishioners ; although he was

chaiged with reading from the Greek Testament, in lieu of the authorised version, to

old Betty Heck, the shepherd's mother,

during her long confinement to her bed

with rheumatism, asthma, and other complainte. Still Betty had alleged that Mr.

Bygrave's reading had done her " a power

of good," although as a matter of choice

she admitted her preference for the visits

of old Mr. Gascoigne.

To Mr. Bygrave I feel that I owe much,

and that acknowledgment of my obllgarions

has been too long delayed.

H e compelled

my acquaintance with a course of literature, concerning which I should have remained without Information b u t for bis

labour and painstaking. I t was no fault

of his that I was but an idle and indifferent pupil, even though something might

be said regarding his defects as a preceptor of extreme youth. But I am sure

tliat he did bis best; I wish I could think

^ e same of my own endeavours.

Our lessons concluded, I often walked

back with Mr. Bygrave part of the way to

the village.

Not that my society was any

boon to him. But I was charged to carry

eertain little gifts of farm produce bestowed upon him by my mother—strong

in her faith that the cui*ate incurred the

perils of starvation from the reckless incapacity and improvidence of his landlady,

ihe wheelwright's Avife. She had been in

times long past, it appeared, a servant at

the DoAvn Farm, and had undergone summaiy dismissal for outrageous neglect of

duty.

There Avas not usually much conversation between Mr. Bygrave and myself

during these walks of ours. H i s notion of

a pleasant topic would have related to the

eonjugation of some Greek verb of a distressingly Irregular pattern, existing only

for the confusion and torture of youthful

students. But I held that such matters

were quito unsuited to discussion out of

school houre. Eor some time I Avalked

[June-. l>:i:

123

silent beside him, carrying a basket of eggs

with rather a boyish longing to upset them,

or to ascertain hoAv far the basket could be

tilted without danfjer to its contents. Proscntly I addressed him upon a subject t h a t

still much occupied me.

" jMr. Bygrave," I said, " did you ever

see Lord Overbury ?"

I t was some time before he seemed to

understond me. H e had to descend, as it

were, from lofty regions of thought to m y

lowly level.

" Overbury, Overbury," he m u r m n r e d ;

" I seem to have heard the name."

Of course he had heard the name. Why,

nearly the whole of Purrington parish belonged to Lord Overbury, Surely everybody had heard the name,

" Overbury, Overbury ? Ah, I remember. No, I never saw him. I t was before

my time, some years. But I heard of It at

the university. I t was a disgraceful affair,

I believe. But I never knew the particulars, nor Avished to know them. H e only

avoided expulsion by teking his name otf

the books. So ended his academical career

—unhappy m a n ! "

W h a t was I to make of this ? Of what

was he talking ?

" I mean Lord Overbury," I explained.

" / mean Lord Overbury," he said.

" No, I never saw him. Nor should I care

to see him."

" He's gone to the great house — the

hall."

" H a s ho ? I don't know that his movements need concern you or me."

And be faA'^oured me with a Latin quotation, which 1 did not quite follow.

Thereupon we parted, for we had arrived

near the wheelwright's. I handed over tho

eggs, none of them broken, and turned

towards home again.

Then I bethought me that I wa.s no

great di.stance from the Dark Tower. W h a t

if I were to steal up the gloomy avenue

once more, and look about m e ?

Surely

no great harm would be done.

I had no plan in view. I was only

moved by a vague and idle curiosity. I

did not look for another adventure, nor to

see tho satyr again. I rather hoped not

to see him ; or 1 should not so much have

minded seeing him provided he did not

see mo. I could not count upon his mood

being so favourable as when wo had met

before. And be might reasonably object

to my Aisiting him again so soon. I t b »rc

a prying look, as I felt.

1 crept furtively up the avenue, stertling

A

124-

[.luno 7, 1873.]

ALL T H E YEAR ROUND.

a cluster of i-abbits tbat I came upon suddenly ; but hardly stertling them more

than they startled me. All Avas wonderfully still otherAvise.

Soon I was close to the great house. I

left the path and bid myself in the shrubbery, peering through a tangle of branches.

The Dark ToAver was dead again. The

windoAV of the room I bad previously

entered Avas UOAV like all the other wlndoAvs ; the shutters were fast closed. It was

as though my adventure had never been.

The house had resumed ite old aspect of

emptiness, neglect, dreariness, death.

I turned to depart, for there was nothing

to induce me to stay, when I heard a footstep close beside me on the moss-coated

gravel walk. Old Thacker confronted me.

I knew old Thacker of course, and rather

feared him. He was rough of speech and

manner, and his temper was sometimes

violent, I had learned to estimate his condition of mind by the colour of his nose,

AvhIch hoisted, as it were, storm signals

Avhen there was peril in approaching him,

A crimson hue proclaimed some cheerfulness of disposition ; but when his nose was

of a deep purple, then he was certainly to

be dreaded ; at such times he was capable

of anything. At least that was my conviction. In the present instence his most

prominent feature wore a rosy glow that

bespoke the dawn of intoxication. It was,

so to speak, in the sunset of ebriety that

tlie deeper tones lowered upon his face and

manifested his descent into wrathful gloom.

He might safely be addressed, therefore,

" I hope you're well, Mr, Thacker," I

said In my politest way.

" Thankee, I be terblish middlin'," he

answered ; meaning me to understand that

bis health was in a tolerable steto. As he

spoke he rattled the contents of a flowerpot he carried under his arm, and furnished

a sort of Castanet accompaniment to his

speech. The flower-pot was full of snails.

I had never before seen any evidence of

his industry as a gardener. " Where bist

ga-ing?" he demanded.

" His lordship said I might fish in the

lake."

" Fish ? There's narra fish there, but

an old jack as big as me a'most. He's eat

up all the rest. He'd eat you if you was

to fall In. He'd eat hisself I do think if

a' could only catch hold of a's tail. Tain't

no mor.sel of use fishing there, lad. So

you caught sight of 's lordship, eh ?"

" Y e s , " I said, " I saw him."

" Well, he be gone agen, now."

" Gone r"

ST

iCondaci«4|y

" Ees ; what a' como vor, there, I danna*,

nor Avhy a's gone, nor Avhcre. 'Tis no »«"

asking, nor thinking. Tain't no bisnesgi

mine, I suppose. Nor no one's else's, moit

like. A' comes and a' goes just when aV]

a mind to."

" You've known him a many years, }b,

Thacker ?"

" Ever since a' was a clytenish (pale)

chit of a child. And I knew a's vather

avore un. Times was diflferent then. But

'tis no use telking. If Farmer Orme's got

a few taters he could spare me, there, I'd bi

grateful.

Mine be uncommon pooriA,

somehows, to bo sure. We be all in ^i

caddie. The old ooman's bad with a coii|^ ^

She took a chill and it pitched, I'm thinking. I be getting these snails for her."

" Snails ?"

" Ees; bile *em in barley water, drink

'em up hot, and they'll cure most u j l

mortel thing."

With this I left old Thacker. I had'

rarely found him in so amiable and communicative a mood.

CHAPTER IX. A STRANGER.

I T seemed clear that I had seen thai

of Lord Overbury, and that my adventum

at the Dark Tower had come to a some*

what tome and prosaic conclusion. Iti

disappointing, certeinly.

As, returned home, I entered the kit*

chen, I was surprised by the spectacle of a

strange figure seated comfortably beside

the fire. Faces one had not seen maaj

times before were rare at Purrington,

rarer still at the Down Farm, and in sndi

wise to be considered with fixed attentioB,

even with a measure of awe. And the fiw

and figure before me were not only new

to me, but presented characteristics that

verged on eccentricity.

I turned to Kem for an explanation. IJ

did not speak, but I was conscious that nf J

open eyes and mouth and startled attitude

had all the effect of intense interrogation.

" An accident," said Kem. "The—-"

she hesitated, I know, as to how she should J

describe the stranger; " gentleman" seemed

not wholly appropriate; she hit upon

pleasant compromise: " The good man"

hurt himself."

" That sounds suicidal," he interpose!

" Rather I have been hurt by a plot

share, I am told, left upon the down^

had missed my way. Night had *

Your roads here are somewhat indistine

Sheep tracks they might almost be called.!

Not being a sheep I was unfamiliar wilh

them, and their nature. I have heard »l

Charles Dickens.]

YOUNG MR, NIGHTINGALE.

^

[June 7. 1S73.]

125

phrase as to the cutting of sticks applied whiskers; his hair, dark, curly, and profuse,

to the movements of man's lower limbs, I was piled u p high above his head, falling

s did not think how literally it might refer upon his brow like a plume. A s I noted

to my own l e g s ; let me be correct—to this he made a circular movement with his

one of them, I was cut on the shin—a arm and passed his fingers through his

tender part as you may be aware—by what, locks, carelessly lifting them to a greater

I am given to understend, was a plough- elevation. H e smiled at me as he did this,

share."

and, I think intentionally, displayed a ring

" I t was t h a t gawney Josh Hedges as he wore upon his little finger. If the stone

IWii

left un there, I'll w a m d ( w a r r a n t ) , " said set in the ring was genuine, I judged that

it must have been, from its exceeding size,

Kem.

" Anyhow it wounded m y s h i n ; not of enormous v a l u e ; but I knew little of

severely, perhaps, b u t sufficiently," con- jewellery; such opinions as I entertained

tinued the stranger. " I fell. I think I upon the subject were derived mainly

&inted. I remained upon the doAvn through- from the histories of Aladdin and SInbad.

out the night. I n point of fact my lodging

I fear that I stared at the stranger with

QjU-jj! was upon the cold g r o u n d ; I will add, and rude persistency; his aspect somehow fasdamp. I have known snugger and less ' cinated m e ; lI louna

found a difficulty in avertpU^, draughty abodes. The bosom of Mother ing m y eyes from him. Not that this

J , Earth is a trifle deficient in natural warmth. seemed in the least to annoy or offend

" I was found by some labouring folks—tiUers him.

I decided, indeed, that he was

mv of the soil ? happy peasantry ? j u s t so. rather gratified than not by my gaze. H e

• u They brought me here, I have received expanded his chest, and leant back majeskindly attontion and succour. Such Is my tically in his chair with an air of exhibitbrief story. You will, I am sure, under all ing his proportions to the utmost advanguuai the peculiar circumstances of the case, ex- tege, and justifying my admiration of him,

or at least my curiosity concerning him.

cuse my rising,"

1

I then perceived that his left foot was Suddenly it struck me that he resembled

tbt IT

* bare, resting upon t h e kitchen fender. H e portraits I had seen somcAvhere—probably

1 ^^!- had been bathing his wound, which looked on market-days in Steepleborough shopw i n d o w s — of King George the Fourth,

WMlK^tliej. an ugly one.

attired

in the clothes of private life.

I- . " Y o u r m o t h e r , " he said, half inquiringly,

1 oteK"i,Qt }jg jjjjj QQ^ wait for an a n s w e r ; " j u s t

H e was scarcely so large in the girth,

lytkespgQ^ I had judged as much—has kindly gone however, as his majesty—judging from his

comloKin search of some further medicaments— effigies—although he was of full habit,

bid not %hat is called * poor man's plaster,' I under- and even corpulent; nor was his costume

are at Pmand. A very appropriate remedy. F o r comparable in point of quality aud fashion

1 FiTii^C hate disguise; I a m not rich, far from it. to the dress of the king. His fluffy Avhito

(fitlfciThus aided, I don't doubt that I shall do beaver hat, bent and battered about tho

ifa«. irery well." H e bowed to me as he lifted rim, and disfigured by many weather stains

vereE- o his lips a tumbler of hot brandy-and- and creases, stood beside him upon the

i\0X^a,ter.

kitchen-teblo. H e wore a blue dress-coat

^ There was a certain oddncss about his of SAvallow-tail pattern, rather Avhite about

)TjnOi^^*°d speech that struck me much. H e the seams, and buttoning with some diffi.jj jQHSCfJvas perfectly grave, and yet there was a culty, OAving to its being a trifle too small

jjijitfinsplclon of comicality underlying all he for h i m ; some of its bright buttons had

jgnstiiik^dand did. Upon my entrance he seemed evidently yielded to the severe tension

J gem '•** ^*^® discerned in me a sympathetic they had been subjected to, and altogether

jjtobo***^'****"* and had addressed to me all his disappeared ; here and there, especially

iigeDtla*^'^**^°°^» ^^^ ^^pt his eyes fixed upon high up on his chest, their places had been

, . jiiefci®'He had a deep fruity kind of voice, and supplied by pins. A rusty black silk ker„ ije frfpoke with a deliberation that was almost chief Avas wound round his neck. H i s lesrs

iboured, as though ho prided himself upon were cased In nankeen pantaloons, tight at

,. 1.) lie '^^ distinctness of his articulation. And as the ankle, but bulging freely, from long use,

hiirt ^ '* *P**^® ^® moved his eyebrows actively, at the knees. A soiled green ribbon Avith

ntii*^?^ waved his hand to and fro in the air. a copper seal and Avatch-key—at least, I

%v!it !>'* '.®®™®<i to gather from my looks replies AA'as convinced that they wero not gold—

his inquiries, nodding his head ap- depended from his fob. Dingy stockings

somf'

,ost^'°^°?'7» ^^^ at intorvals permitting a and very thin shoes—that had not recently

^'^' ki^^^^

Bmlle to flit across his lips. H o undergone blacking, and certeinly needed

repair—completed his altire. Beneath his

a large. round, fleshy face Avithout

\ ^

12C

[JutiP 7. 1873.J

ALL THE YEAR ROUND.

chair there rested a small bundle tied up

in a fadetl cotton handkerchief knotted at

the coniers, and attaidied to a rough Avalking-stiek. Avhich looked as though it had

been drawn from a hurdle.

I felt that 1 bad been staring at the

stranger quite long enough ; still I could

not depart from his presence.

1 had noA'er

before seen such a man, or such a method

of dress. But 1 now changed my position,

and for awhile studied the movements of

Kem and the condition of the kitchen fire.

Every now and then, hoAvever, 1 Indulged

in a furtive glance at the .stranger. When

1 did so, I found him still looking at me.

Our eyes met. I t Avas certeinly awkward.

And then my curiosity Avas newly stimulated. H e had produced from bis pocket

a pair of scissors and a scrap of paper.

And, Avhilc still looking at me, he was

snipping at this paper, holding it up to the

light, then snipping it again, after further

gjizo at mc. H e Avas a most extraordinary

man. H e had already been too much for

Kem. She was stricken dumb, and, as she

Avildly pared potetoes, her face wore almost

an In.sane expression.

" I call t h a t a fair portrait," said tho

stranger, and he held up a black shade of

myself, placed against a Avliite card for ite

better exhibition.

H e had been cutting

out my silhouetto. K e m was roused from

apathy, and as .soon as her amazement

permitteil her speech, she pronounced the

portrait perfect, said she .should have known

it anywhere, and evidently formed forthAvith a more faA'ourable opinion of our

visitor than .she bad previously entertained.

1 felt that the black shade resembled me,

though I was but indifferently acquainted

Avitli the conformation of my OAVU profile.

Still it exhibited a boy Avith a blunt nose,

a sharp chin, a mass of thick untidy hair,

and a patch of white to represent my collar.

I t Avas clearly my likeness.

" Y o u ' r e an artist, sir," I said, diffidently.

" I may call myself an artist," he anSAvered, Avith a grand yet not unkindly air.

" I really think I may. Not that this

trifliiifj is really to be called art. You like

the trifle r—keep it, my young friend. Keep

it, my friend. In memory of me. A touch

of gum or paste will make it adhere to the

card.

Slick it up over your mantelshelf.

Tell yonr friends, should they inquire, that

it is the work and the gift of F a n e Mauleverer. A trifle, yet of worth In its Avay.

I've known worse portraits executed by

artists of greater pretence.

But I am in

the habit of speaking modestly—if at all—

of my OAvn merits."

V

-/"

[Conducted by

I was deeply gratified; I tendered hiia

warm If incoherent thanks, which he r».

ceived with bland and sinlling deprecatioaj

I Avas even emboldened, boy-like, to ii

trude further upon his generosity,

begged further demonstration of his ai

endowments.

" Now do K e m ' s likeness; please, do^"

I pleaded. H i s kindness had banished my

timidity.

" I'm ashamed of you. Master Dnka^f

said Kem, the natural crimson of her face

deepening greatly.

She objected to

portrayed.

She had even some a

stitious apprehension, I think, that enl

would come of it. She covered her fiw

with her apron.

B u t the stranger—Mr. F a n e Maulevewr

as he h a d announced bis name—with ia

amused expression, snipped a fresh acof

of paper, and not in the least deterred \^

her movemente and objection, achieved a

silhouette of Kem. I t h o u g h t it wondatf

fully like—much better t h a n my own, in^'

deed, of Avhich, perhaps, I was not so gooi

a j u d g e . H e r cap strings and frills w a i j

beyond praise.

" By special desire," said Mr. Manleverer,

exhibiting his work, " of tho young gentlaman Avhose name I gather to be Duke, i!

portrait of the exemplary lady whom t

have heard designated K e m — a curiona

appellation; b u t no matter. Here is F a »

Manleverer's tribute to the personal advwft^

tages of Mistross K e m . "

My mother entered the kitchen. She

was much distressed at the mischance that,

had befallen Mr. Manleverer. She wa»

about to apply her healing arts to BI

wound; the matrons of her time

practised in domestic medicine, and an

had long been consulted upon all accidenil,

happening upon the farm.

B u t Mr. '

leverer, Avitli exceeding politeness, decli

her aid. H e could not permit, he i

that she should attend upon him. Andl

called her " My dear m a d a m . " His

ner struck me as quite courtly.

" No, no," he said, " I a m not the

valier B a y a r d . " I t occurred to me that|

did not resemble greatly m y idea of

chivalric personage. " A n d my woi

but slight, and not received in

but ignobly, by Avandering from my

and tumbling over a useful, if _

agricultural appliance. A strip or tWfl

p l a s t e r — s o " — as be spoke ho wanned i

plaster at the fire, and then appHed it]

his h u r t — " and then, I am myself ag

may limp for a day or two. But wl

matter ? I can yet proceed upon my

A

Chariea Dickens.]

FAMOUS BRITISH REGIMENTS.

^.

" You were going to" To Lockport. I had left Dripford in

^ the morning. My trunks, I may mention,"

4 here Mr. Manleverer looked very grave and

ws- cleared his throat, " have been sent on beih fbre me. I was told that Lockport was a

walk of some twelve miles."

j'*

" Across the down."

lluiiL' " True. Across the down. But a stranger

to these parte—I was never before, indeed,

ke; in this delightfully open country—I missed

ionoii HiJ road. I t was not surprising, perhaps.

pk: Nor could I obtain directions. One meete

a m but few people hereabouts; habltetions are

Hint ^ scarce, and sign-poste are not frequent

jyaiis when once the highAvay has been quitted.

Bnt now, rested and refreshed—thanks to

^jBSJI^ yonr kind hospitality—and my trifling injjjf^ jury seen to, I think I may safely proceed.

jjljjj He rose, and took his fluffy white hat

l^^^firom the teble.

^^,^ " I t were best for you to remain," said

jjj.jj;j,my mother. " A night's rest, Mr.

"

^^^,8he paused.

I "j "Manleverer — F a n e Manleverer," he

igsaid, bowing over his hat Avhich he pressed

> against his chest.

,,[ jr " We have a room at your serArice, Mr.

'. Manleverer. All shall be done for your comfort. I t is not right t h a t you should set

'^ ..forth so soon—night will soon come on—

^ • and your hurt is too serious for you to think

•^'^of walking so great a distence."

tw "•' " Madam, you overpower me. But—let

iMpffi^me disclo.se myself. You may entertein

. mistaken notions in regard to me. I am

the 0!*ui actor, madam. Nothing more. A poor

the ci^layer on my Avay to Lockport, having an

nlere^ ingagement there during the race-week.

lealicz '^i have trod the boards of Covent Garden.

ot' li^ -But I am now, at your service, a strollmeditf'ng player—that Is the world's description

inpcD^tf me. I am content to accept it as suffi^ B<iiently accurate."

lOt

FAMOUS B R I T I S H

iltJ

-j^jjj iBB FIFTH FOOT ( " T H E

REGBfENTS.

FIGHTING

FIFTH.")

^k

THERE is an old militery tradition that

^j^i'he Fifth won from the French the fea^[oJhers which they UOAV wear, and that

I ji,f>bey dyed their tops red by dipping them

* y ' j j l the blood of their enemies. The true

•^jjiborv, however, is this. The " O l d Bold

^ ^ ^ ^ h " had tho distinction of wearing a

^ -J ji.fhite plume in the cap, when the similar

^ ^l^xnament in the other regiments of the

^ j^fiOrrice was a rod and white tuft. This

•P^ 2i;|Dnonrablo distinction Avas given to them

i ^^ J;ir their conduct at Morne Fortune, in the

I ^ ' iland of St. Lucia, whero they took from

[June 7,1S7:3.]

127

the French grenadiers Avhite feathers in

sufficient numbers to equip every man in the

regiment. This distinction was subsequently

confirmed by authority, and continued as

a distinctive decoration until 1829, when

a general order caused the white feather

to be worn by the whole army.

By a

letter from Sir H . Taylor, adjutant-general, dated July, 1829, the commanderin-chief, referring to the newly - issued

order, by which the special distinction was

lost to the regiment, states that, " As an

equivalent, the Fifth shall in future wear

a feather half red and half white, tho red

uppermost, instead of t h e plain white

feather worn by the rest of the army, as a

peculiar mark of honour."

The Fifth Regiment of Foot (or Northumberland Fusiliers) originated in a body

of disbanded Irish soldiers, who, on the

peace Avith Holland, in 1674, were allowed

to enter the Dutoli service. It had been

Intended to raise ten thousand men, and

place them under the chief command of

the Prince of Orange. Sir Walter Vane

was to haA'e been their leader, but he

being killed at the battle of Seneffe, the

command was handed over to Sir William Ballandyne, who Avas shot the same

year at the siege of Grave, in North Brabant. Colonel John Fenwick then took

up the dead man's SAA'ord, and led on

the " I r i s h " regiment to many Dutch

victories.

At tho great but unsuccessful siege of Maestricht, which Avas defended by Monsieur Calvo, a braA'c Catalonian, and eight thousand men, the

English brigade distinguished themselves

by repelling several hot .sallies, and capturing, after two bloody assaults, the

Dauphin Bastion, for Avhich the Prince of

Orange complimented the Irish corps, and

rewarded the men Avitli a special present

of a fat ox and six sheep to each regiment.

In this siege, raised at last by Marshal

Schomberg and a French army, the English brl2;ade had nearly half ite officers and

men killed or Avounded.

A t the defeat of the Prince of Orange

at Mont-Cassel iu 1677, the Irish bricrado behaved Avith its usual indomitable

spirit. In 1678, under the command ot

the Earl of Ossory, the regiment fought

in the Netheilands, and is particularly

mentioned on one occjision as encamping near Waterloo ; Avhile at the battio of

St, Denis, the British brigade Avas chosen

to lead the atteck on the French. The

regiment lost on this occasion about a dozen

ofliccrs, eighty men killed, and one hundred Avouuded. Tho peace of Nimegueu

=5*

I

^

i5=

128

[June 7. 1873.)

ALL T H E YEAR ROUND.

soon followed, and for a time tho brave

brigade hung up their ponderous mu.skete.

On the accession of James the Second,

the rebellions in Scotland and England

compelled the return of the English and

Irish regiments. They arrived too late to

be useful at Sedgemoor, and sailed back at

once to Holland, from Avhence, in 1687, they

refused again to return at the king's command. The prince then bestoAved the

colonelcy of the .subsequent Fifth on Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas Tollemache. Capteln Bernardi, of this regiment, was afterAvards Implicated in a plot to assassinate

King William; and, though never tried,

Avas cruelly detained in prison by that

usnally just king for thirty years.

When the Prince of Orange sterted for

the English throne in 1688, Tollemache's

regiment was the flower of the five thousand five hundred men Avho left Holland,

and It at once obtained rank as Fifth Regiment of Foot in the British line. They

Avere soon busy in Ireland, fought at the

Boyne and the siege oi Athlone, and cut

to pieces many troublesome packs of Rapparees. At Athlone the grenadier company

of the Fifth, under Major-General Mackay,

Avaded breast high through the Shannon,

the reserve following by planks laid over

the broken arches of a stone bridge. The

regiment afterwards joined actively in the

siege of Limerick, and the conquest of that

place terminated the war in Ireland.

It is a noteworthy fact that in 1694, during

William's wars in Flanders, the Fifth Averc

again encamped near Waterloo, and they

also helped to protect Ghent and Bruges,

in 1696, from tho French. In Queen

Anne's Avars they also had hard work cut

out for them. In the war of the Spanish

succession they fought a good deal in

Portugal; and at Campo Mayor, when the

Portuguese cavalry fled, and three of our

regiments, advancing too far unsupported,

Avero surrounded and taken prisoners, the

Filth and two other regiments made a

stubborn stand, killing nearly a thousand

Spaniards and effecting a brave and glorious retreat Avith a loss of only one hundred

and fifty men killed and wounded. After

this Portuguese campaign, the Fifth (five

hundred strong) went to garrison Gibraltar, and remained there fifteen years.

In 1726, they helped vigorously to defend

the tough old rock against the Spaniards.

In 1728, the Fifth proceeded to Ireland,

where it remained, with but a short interval,

for more than tAventy years. In 1755 it left

Ireland, and in 1758 Avas sent to effect a

landing on the coast of Franc.', Avbjn it

[CondoelMby

helped to burn the shipping and magazines

at St. Malo. In August of the same year it

helped to destroy the fort of Cherbourg, and

to capture and destroy one hundred and

eighty-five cannon, and, the month after, it

was sent to land in Brittany and destm

batteries.

In 1760, the Fifth fought under the Dnki

of Brunswick in Hesse Casscl. In 1761,

as part of the Marquis of Granby's corp^

the Fifth defended tho heights of Kirct

Denkern, and helped to take prisoners tbe

whole Rouge regiment, with its cannon

and colours. When Prince Frederick smw

prised the French camp at Groebenstei^p

the Fifth attacked Sterville, who had

throAvn his division into the woods ol

Wllhelmsthal, to cover the French !••

treat. Tho Fifth wormed through tint

Avoods, firing from tree to tree, while the

Marquis of Granby attecked the Frenok

rear to prevent tho retreat. The Fifth

took more than twice ite own number

prisoners, and finally helped to capton

the whole French diArision, except two

battelions. An officer of the Fifth, who hk

went up to take the French colours (tan

the standard-bearer, was shot dead by a

French sergeant, who stood near; but the

man was instently killed, and the colours

quickly seized. The Fifth earned so modi

credit for this dashing exploit, that tbe men

were allowed for the future to wear French

fusilier caps, instead of the hat then nsed

by tho regiments of the line; and in 1836^

William the Fourth allowed the regiment

to bear the word " Wilhclmsthal" on their

colours and appointments.

From 1764 to 1774 the regiment »•

mained in Ireland, where, from the cleafr

ness and trimness of the men, the soldien

of the Fighting Fifth became known as "flie

Shiners." Early in 1767, orders of merit

were instituted in this regiment with great -ui

success, as they served to insure good noncommissioned officers, and to rouse the

ambition of the privates. The first (seven

years' good conduct) earned a gilt mi *'

bearing on one side the badge of the

ment, " Saint George and the Dragon,"

with the regimentel motto, " Quo Fata vocant," and on the reverse, "¥'•» Foot,

merit;" the second medal (fourteen yean

merit) was of silver; the third, also silvff

(tAventy-one years), bore the name of thi

wearer. Those who gained the twenty-one *»;

years' medal had an oval badge of the

colour of the facings (green) on the rigW

breast, surrounded with gold and silv*

wreaths, and inscribed in the centre wiA 3;tiT

the Avord " merit," in gold letters.

•'^'h

^

Jh

"^

Chi

Chariea DIekens.]

FAMOUS BRITISH REGIMENTS.

ThePifiEh, in 1771 and 1772, served in

Ireland against the wild bands of Whiteboys, Hearte of Steel, and Hearte of Oak,

and in 1774 went to p u t down the so-called

rebellion in America. They fired the first

shot of the unfortunate war at Lexington,

where they came on some armed American

militiamen,

and were nearly surrounded at

i\

Concord, where they had destroyed some

ok' militery stores collected there by the socalled rebels. I n the attack on Bunker's

Hill, near Boston, the Fifth had hot Avork

for a June day. W i t h three days' provision

on their back, cartouch-box, &c., weighing one hrmdred and twenty-five pound.s,

ilkii

they tolled through grass reaching to their

jTr" knees, between walls and fences, in the face

I j ^ of a hot fire, and eventually got possession of the enemy's works on the hill near

tntr,

Charlestown, The Fifth also joined in the

reduction of Long Island, tho battle of

eat. Il

White Plains, the capture of Fort Washrj'J' ington, the reduction of NCAV Jersey, and

'P" a fight at German town, where they rescued

f"; ^ the Fortieth regiment from an American

[June 7, 187.3.]

129

on a place of no less importance than the

market-square, but Avhich, by the assiduity

of the enemy, had been transformed into a

species of citedel. Our gallant and highspirited officers fully coincided with the

major's views. W e had a sergeant with

us, George GoUand, who, I verily believe,

would have sabred the first man shoAving

symptoms of what he never felt—fear.

Such was our enthusiastic confidence in

our leader, that when, sword in hand, he

exclaimed, ' Now, my brave fellows, death

or victory,' onward we went, and on turning the first angle to the left, found ourselves in the street leading to the marketplace. Here we were exposed to a galling

tire, which, though It thinned the numbers

of our little band, did not impede our progress nor damp our ardour till AVC came to

the square at the end of the street. H e r e

a close, compact, and well-connected fire,

Avounding several of our officers and men,

whom was our noble major, comamong

pelled us to r e t r e a t ; and it Avas fortunate

that we Avere able to effect it

We,

however, managed to bring our wounded to

''^^

In the expedition against the French a church, converted into a hospital, Avhere

sl«"West Indian Islands in 1778, the Fifth they Avere put under the care of medical

wita took part. I t was at St, Lucia, as Ave have officers, protected by a sergeant's guard,

.''"'^already seen, that the regiment won its of whom, by turn of duty, I made one.

II OTBi ^hite plumes, helping to repulse three de- Sergeant Prior, of Captain Clarke's comploitta: termined rushes of seven thousand French pany, and Corporal Byron, were the nonSoon after the

BBKgent to save the island. The French lost commissioned officers.

theksfour hundred killed, and eleven hundred regiment was gone, some of the twelve

line; J:; wounded, while the English lost only men left on guard went into a wine store

ijtei lis'eighteen men, and one hundred and thirty close by, and tAvo of them, from want of

idas^ wounded—a disparity t h a t seems almost food and excitement, soon became intoxicated, and on attempting to cross the street

3. incredible.

tkRP In 1787, the regiment embarked for to return to us Avere shot dead. To pref^gti:-Canada, and in 1796 was employed against vent a similar disaster the sergeant directed

5 nenithe insurgent Canadians at Point Levi, and a sentry to be placed at the door of the

^^it^ctoaaed the St. Lawrence on the ice. In wine house; and he, too, soon shared the

;; (pjsl797, the officers aud sergeants returned to fate of his comrades from the fire of a con^^dBngland, and re-formed the regiment by cealed enemy. T h e sergeant then took his

Jiiistisirecruitlng in Lincolnshire. A kindly feel- sta,tion there ; in a few seconds he also was

ij to ing was from that time esteblished between a corpse. Night approaching, Byi'on and

, <^':^he Fifth and Lincolnshire people, that stilltiie rest of us began to think that our post

^jpjjOrings many recruite annually to the regi- was not tenable. W e shuddered at the

idea of leaving the wounded, and came to

yjfjaient from that county.

the

resolution that one of us should en' 1 ,i|,; After serving in the Duke of York's re(.(jjiiarkablo campaign in Holland in 1799, deavour to find the regiment and procure

' ihe Fifth went for two years to Gibraltar, assistence. I t was a dangerous adventure ;

' . ii^/etuming at the peace of Amiens, I n 1806, Ave cast lots ; and the chance fell upon me.

f^liii'^® l a m e n t had its share of the mortifying W i t h piece loaded and bayonet fixed I

1'^, jjiefeat at Buenos Ayres—a defeat Avhich ventured down the street, cleared it, and

Avith but one interruption succeeded in

r«j°^j^e Fifth did its best to prevent. After

making my way until ' W h o comes there'

iD^ l^^,utering tho treacherous toAvn our soldiers

announced that immediate danger Avas

of^ rt^'und themselves in a hive of riflemen.

over. I found Colonel Davie, Avith Avhom

?i^,', ^ "However, cheered by hope," writes ono

Avere Majors King and Watt, and most of

t h f / t h o Fifth, " w o assembled In a yard, the officers, and explained to them my

ill"' 'here our brave major proposed an attack

J* J-brigade.

I

v^

\ i

l "

130

[Junp7. 1H7.T]

ALL THE YEAR ROUND.

mission. The colonel replied, ' I t is too

late; the guard is disposed of; join your

comp:iny.' I did so, and to my utter a.stonishnient leai'ued (he issue of the dav's

adventure, namely, that the light brigade,

Avith Colonel Crawford, Averc prisoners;

this included onr light, or Captain G. B.

AV'ay's company; Captain Hamilton had

lost a leg."

The uniform of the regiment In 1804,

Avas a long-tailed coat, Avhite pantaloons,

and Ilesfiian boots; with hair tied and

powdered, and a cocked hat. This was the

dress of the officers, to which that of the

stafl-sergeants bore an affinity in the hat and

silver-laecd coats. The dress of tho men

when on fatigue was perfectly AvhIte, except

their stocks, queues, and shoes; but when

they were dressed for parade, their coats

Avere frog-laced, with facings of gosling

green, white breeches with gaiters, the hair

being tied, and well AA-bltened with flour !

In the summer of 1808, the first battalion,

under the comm.and of Lieutenant-Colonel

John ilackenzie, sailed for Portugal to join

the ai-my of Lieutenant-General Wellesley.

I t climbed the rocks of Rolela, gallantly

fought at Vimiera, and shared in the disastrous retreat of Corunna. A sergeant of

the Fifth, Avho was present at Roleia, has

left a pleasant picture of the gallant clamber

u p to the French. " O u r .staff officers," he

.says, " soon discovered certain chasms or

openings made, it should seem, by the rains,

n p Avhich AVC were led. As soon as we

began the ascent. Colonel Mackenzie, who

was riding on a noble grey, dismounted,

turned the animal adrift, and, sword in

hand, conducted us onwards until we

gained the .summit of the first hlU, the

enemy playing upon us all the time.

H a v i n g gained the crest, we rushed on

them in a c h a r g e ; whoever opposed us fell

by the ball or bayonet. W e then proceeded towards another hill, where the

enemy had formed again ; but as our route

lay through vineyards, we were annoyed

by a destructive fire."

A t Vimiera a curious artifice was resorted to by the Fifth to get into the battle.

" O u r situation," says one of t h e Fifth,

" was on the slope of an eminence; we saw

our people promptly advance against the

enemy's masses, which Avere formed in

column, and with which they boldly attempted to break the British lines. The

attempt was vain, although they were ably

assisted by their ordnance and howitzers,

from the latter of which we saw the balls

rise high in the air, and after describing

•2^

tCondndtety

many segments of a circle, generally JJJ

between our people Avho were adAraneioff

and ourselves. Dense smoke soon afiv

enveloped the belligerents.

I t was thai

Ave found our situation Irk.some, many of

our oflicens too high-spirited to be thru

shut out of tho glowing scene, actually left

us, and ran into the battle. Those who

remained contrived a scheme for the chanoa

offolloAAing them. W e heard our bngfci

sound the charge ; we heard, or fancied m

heard, tho enemy's fire growing strong^^

when from the right of us idlers arose flii'

cry, " The colonel is shot I" His ladyhefr

ing this rushed through every restraial

doAvn the bill, which was an excuse for monr

of our men to follow in protection. A l ^

pieces pointed at them from our picke|ii^

frustrated this ruse de guerre, for happOyB

was only a ruse to get Into the melee, the

colonel not being even wounded. Towwdl

the end of the day, t h e scene of aelaoa

having receded, we were directed to a (

vance, Avhen, coming u p with the regiment;

we had the pleasure of seeing the eneor

in full and unequivocal retreat."

A n eye-witness of the bravery of tba mw

Fifth at Salamanca says, " The light »

gade—the light infantry companies of eael

division—were soon entering into a deili

in our front, at about a mile dial

M:

These were followed by some

liiinoi

F i r i n g soon commenced. The troops

k:

to their a r r a s ; they advanced; we were 'btl

soon within range, when each parti

regiment, as its flank became un©

Hat?, lit

deployed into line, and advanced to tiiil

attack. A few minutes before this, Sergeants Taylor, Stock, Benson, Bernard,

Green, Watson, and myself, were ordered "litrai

to the centre, where we found ~

J a m e s B. Hamilton and another, who

the colours. The shock of the onset had

passed over, the men expeditiously firing,

and gradually gaining ground. We wir»

going u p an ascent on whose crest massK

of t h e enemy were stetioned; their firt

seemed capable of sweeping everything

before i t ; still we advanced; the fire ll>

came stronger—there was a panw-"*

hesitation.

H e r e I bltish; but I should

blush more if I were guilty of a felsehood.

T r u t h compels me to say, therefore, that««

retired before this overwhelming fire, Inrf

slowly, in good order, not far ; not a hundred

paces. Sergeants Stock and Taylor were

already killed, when General PakenhaB

a])proached, and very good-naturedly«

'Re-form,' and in about a m o m e n t "

vance,' adding, ' T h e r e they are, my

'A=

Chariea DUAtaK

REMEMBERED.

[June 7,1S73.]

131

just let them feel the temper of your bayo- Grant. For conspicuous devotion at Alumnete,' W e advanced, every one making up bagh, on the 2 k h of September, 1857, in

his mind for mischief.

Proceeding rather proceeding under a heavy and galling fire

slowly at first, the regiment of dragoons, to save the life of PriA'ate E. DeA'eney,

which had retired with us, again accom- whose leg had been shot away, and evenpanying us, at last we brought our pieces tually carrying him safe into camp with the

to the trail, the fire still as brisk as before, assistance of the late Lieutenant Browne

when the bugles along the line sounded the and

some comrades. — PriA'ate Peter

charge, Foi^'ard we rushed ; the scene was M'Manus. A party, on the 26th of Sepsoon closed, and aAvful Avas the retribution tember, 1857, Avas shut up and besieged

we exacted for our former repulse. . . J u s t in a house in the city of Lucknow by the

after. Ensign Hamilton was wounded ; we rebel Sepoys. Private M'Manus kept outhad lost Sergeant Watson and a n o t h e r ; side the house till he himself Avas wounded,

80 to prevent the colours falling, the officers and, under cover of a pillar, kept firing at

being wounded at nearly the same instant, the Sepoys, and prevented their rushing on

Sergeant Green and myself had the honour the house. H e also, in conjunction Avith

of bearing both colours for upwards of an Private John Ryan, rushed into the street

hour, a circumstance which served as a and took Captain Arnold, of the First

pretext for throwing away my pike, a useless Madras Fusilier.s, out of a dhooly, and

piece of militery furniture. W e continued brought him into the house in spite of a

to gain ground on the enemy until we heavy fire, in which that officer was again

arrived at the crest of a hill crowned by Avoundcd.—Private Patrick M'Hale. For

our own artillery, which Avas acting against con.spicuous bravery at Lucknow on the

that of the enemy on an opposite ridge, a 2nd of October, 1857, when he was the first

valley being between them. On arriving man at the capture of one of the guns at

with the artillery we paused for breath, ; the Cawnpore battery; and again, on the

when we were commanded to clear the hill 22nd of December, 1857, when, by a bold

on which the enemy's guns were planted. rush, he was the first to teke possession of

This required celerity of movement; we one of the enemy's guns, which had scut

ran down our hill exposed to the enemy's several rounds through his company,

fire, as well as for part of the distance to which was skirmishing up to it. On every

that of our own. Complete success crowned occasion of attack. Private M'Hale Avas the

our efforts; the enemy, routed, left their first to meet the foe, amongst whom he

guns, when the line, an extensive one, com- caused such consternation by the boldness

posed of several regimente, halted. Night of his rush, as to leave little work for those

r ^ j advancing, little more than a desultory tire Avho followed in his support. By his hawas mainteined, and soon after, it being bitual coolness and daring, and susteined

known that some of the commissariat had bravery iu action, his name became a

arrived close in the rear, I Avas ordered to household Avord for gallantry among his

take a sergeant of the company, and draw comrades."

•pirite for the regiment,

I Avent, the adMost true English soldiers are ready to

jntent accompanying me, when, having go Avhere the trumpet calls, " Quo Fate

.Jtaved in the head, I was so completely v o c a n t ; " but the Fates, as we have pretty

{^•''

^. overpowered with thirst, tliat I drank very clearly shown, have called few regimente

if^jiUearly a pint of rum without feeling its to hotter places than the Fifth, and few

ffgrtOt-^ itrength. Returning to my station in the

regiments have obeyed the call with more

n ''"*.'. centre, I learnt the result of this Avell- joyous alacrity.

5t»ti*J^ fought battle."

gwefp^'i' In the Indian campaign, the Fifth fully

jyjBce^:'.earned ^ ^ blazon of " LucknoAv" that still

re **•' adorns their flag. I n tbe full head of an

blisli'j Indian summer they faced the matchlock

.(foiitT'' fire of the Avhite-capped Sepoys, and the

ggy^tli^' sabres of the rebel so Avars; aud many a

^jjffktb^ blood-stelned " budmash " fell by their

ji(,(fir:'J fierce bayonets, Tho records of the Vic.^^tiC' toria Cross contain the names of several

(jgiifi* heroes of tho Fifth, as the following ex^•t«* tracte prove:

^^^itlf " F i f t h Regiment. — Sergeant Robert

-^

'

'

,

'

I

EEMEMBEKED.

OsLT a great green meadow, with an old oak-tree in the

hedge,

Wbc't' tliR bram1)l<'.s were first to ripen, the sparrow

was tirst to lledge ;

Oulj a bmad brown nvor that swept between willow

ranks,

Where the tansy tingled the bindweed fair that graced

tbe sandy bauks.

Just the meadow, and the river, and a Une that joined

thetwi>,

And ll marsh where marigold glistened, b j forget-i

nots' virgin blue,

y

^

A

132

(June 7,1S73.]

ALL T H E YEAR ROUND.

[Condnettdby

4

With the purple bills fcr a background, and a lark that j g o o d p l a i n way.

as tho old-fashioned

always sang.

cookery-books say—wc start from the

Till the bright keen air around it with the melody Roman rallAvay station close by the huge

trilled and rang.

pile of ruins knoAvn as the Baths of Diocle.

It is thirty weary years ago. Through many a lovely

tian, at half-past seven o'clock on a dascene,

Through many a fair and storied haunt my tired stepa licious spring morning.

httvo been,

Our felloAv-travellers arc not very nQ>

Yet, wlunever from life and its lessons I turn, a supmerous.

The hour is too early for

pliant guest,

To tbe land where memory shrines for us beauty and the majority of citizen holiday-makers.

joy and rest.

There are several parties of sportsmen

I know the scent of the tansy, crushed 'neath an eager armed AvIth guns for the slaughter of small

tread,

I know the note of the skylork as it soared from its birds, and attended by a dog in a leaah,

usually of a currish aspect. There are five

lowly bed,

I see the oak-tree's mighty boughs, I hear the willows or six shop-boys In a chattering groups

shiver,

I see the blue forget-me-nots that grew by the northern dressed like the wax figures in a cheap

clothier's AvindoAv, aud assuming great ain

river.

There are a few

Fancies have failed nrd hopes have fled, and the prize of fashion and dandyism.

but mocks the strife.

officers in uniform, a priest or two, and

Death aud .Sorrow with busy hands have altered the

some peasant Avomen Avitb empty baskets.

course of life,

Dut as fair and fresh as whendo^n its path the fearless These latter have, doubtless, been selling

foot^tep sprung,

garden produce In the capital, and are re.

Is the meadow beside the broad brown stream I loved

t u r n i n g to their homes to pass the festal

when all was young.

MODERN ROMAN MOSAICS,

A ROMAN HAMPSTEAD.

donkeys, plenty to eat and drink,

and a whole Sunday to enjoy them in !

Here be materials for a cockney holiday,

or I have never been within sound of Bow

bells!

But—there are hills and hills,

donkeys and donkeys, food and food ; one

must discriminate.

Dear old Hampstead, I am not going to

say a word against thee. Let those AVIIO

have no eyes to see, and no soul to enjoy

the Avonderful view from Hampstead Hill

Avhen the summer sun Is setting; and who

have no fibre of sympathy witb the holidaymaking toilers and moilers who trudge out,

men, Avomen, and children, to gratify their

intensely English longing for a glimpse of

rurallty—let such fine folks, I say, turn u p

their honourable noses at the humble enjoyments of the Londoner's familiar 'Amstead

'Eath, and search in their foreign guidebooks for leave to admire " by authority."

Not of such am I, nor would I be. F a r

be It from me to disparage thee, oh, thou

donkey-traversed Arabia Felix of my childhood 1 B u t still, as I began by observing,

there are hills and hills, and one must discriminate.

The holiday resort which we are to visit

on this bright Sunday at the end of March,

is a bttle townlet on a spur of the Alban

Mountains, and the great city Avhich it looks

at from its terraces and Avindows, is called

Rome

To begin a t the beginning—which is a

HILLS,

Cff

day.

I n Rome most things have a character

of their OAVU. W e live and move on a mere

crust of nineteenth centuiy, but immediately beneath it lies the solid foundation

of some two thousand and odd years aga

And one has but to scratch the soil a veiy

little, to scrape away every vestige of "t».

day," and come to the abiding traces of the

ancient Latins. Nay, in many places their

works still toAver by tbe head aud shonlden

above t h e soil ; although Time toils ceaselessly to heap the earth over them, and

bury them Avliere they stand. The steans

horse puffs and clatters along through I

breach In the city wall, past the ruins oft

great temple, said to have been dedicated

to Minerva Medica (or as a modern Bomn

might style the diArinity, Madonna delk

Salute, Our L a d y of Healing), pastths

tall arches of hoary aqueducte, past monndl

of immemorial antiquity, and crumbling

tombs, AvhIch have survived for so many

centuries the memory of their builders and

occupants.

The grass is brightly green

with the fresh life of the early y«ff'

W h i t e daisies cluster, by thousands and

j hundreds of thousands, over the meadowsrf

the Campagna. Siieep are grazing peace- i(l

fully, and do not t u r n their gentie, sIDy

heads as the train whirls noisily past them.

Some great huge-horned oxen lie resting

Avith their dove-coloured sides half buried

in the herbage, and their jaws moving

AvIth slow and regular motion as they cbe*

the cud and stare a t us contomplativeljBirds are tAvittering and piping cheerfoUji

restless aud swift of wing. Out yonder J»

OP

Charles Dickens.]

MODERN ROMAN MOSAICS.

the distance rise the shadowy blue mountoins, whither we arc speeding along the

iron way,

A journey of little over half an hour

brings us to the station of FrascatI,

which is about a mile from the town, and

three or four hundred feet below it. All

around us are dusky olives, and young

vines, and peach-trees in full bloom. H o w

exquisitely the vivid delicate colour of the

peach-blossom contrasts with the chocolatebrown of the ploughed earth, the purplish

tint of the still leafless branches, and the

green-grey of the olives ! B u t there is no

time now to stop and contemplate t h e

beauties of nature, A crowd of men and

boys driving a great variety of vehicles,

and saddled donkeys, make competing offers

for the honour of conveying us to FrascatI.

We j u m p into a high gig drawn by a short,

fat, black pony; the driver perches himself

partly on our knees, and partly on the

outer edge of the little vehicle, and off" we

jingle up the paved road among the olive

plantetions.

FrascatI has a large open piazza, and an

iigly big cathedral—built at the beginning

of the eighteenth century, and a good

specimen of the tastelessness of the period

—an inn, a fountain, some tolerable private

houses, and a labyrinth of evil-smelling

back slums. And of course there is the indispensable cafe with tebles and benches In

front of the door, and spindly oleanders in

tubs. The piazza is full. Men stand, and

lounge, and smoke, and chat, or remain Avith

their hands in their pockets, simply enjoying

in its literal significance the dolcefar niente.

The church is full, chiefly of women and

children; the trattoria (eating-house) is

full; Avorst of all, the inn is full.

" Beds ? Nossignore ! not a bed vacant

in the h o u s e ! B u t we will find you

quarters in a private dwelling, and you

can eat in the hotel. Non dubiti, don't be

a&aid, you'll do very well."

W e do find an apartment in the house

of the hairdresser ( I apologise to the other

capillary artists, if there be any other in

FrascatI, but truly I believe our host was

the hairdresser), where wo deposit our

travelling-bags, and then proceed to bargain for donkeys and a guide to convoy us

to tho sights In the immediate neighbourhood. Villas there are to be seen, and a

gfreat Jesuit monastery and school, and

above all, Tusculum! Tu.sculum the ancient,

mined, fortress-city, and tho villa, so-called,

of Cicero, scene of the Tusctdan disputations.

^^

[June 7,1373.]

V-i.)

This is a cockney excursion, and we aro

not going to be learned, and instructive,

and guide-bookish. B u t let us be never so

humdrum, and of the city citified, the fact

remains that we are treading on classic

ground, and cannot make a step without

arousing some echoes of the wonderful and

mighty past.

Nevertheless, our Roman Hampstead has

its banalites and vulgarities. You are

told to visit this villa, and that villa, and to

admire their painted ceilings, and waterworks, and marbles, and views. These

latter are, in truth, superb; being unspoilable by any combination of money and bad

taste. B u t of the rest, the less said the

better. The Aldobrandini Yilla, the most

celebrated of these, is finely situated, and

has some noble trees in its grounds, and an

abundance of clear delicious Avater."" The

beauty of the water is, however, greatly

marred by the hideous artificial cascade

down which it is made to pour, in the

centre of Avhat the guide-books call " a fine

hemicycle with two wings." The " liemicycle" is a crescent-shaped stone arcade, of

about as much architectural beauty as the

arcade yclept of Lowther in the Strand.

Once upon a time the Avater Avas made to

t u r n an organ, and perform other fantestic

t r i c k s ; but fortunately the works have

fallen out of repair, and AVO are spared

having to waste our time on that spectacle.

This it is, though, and such as this, that

our guide chiefly insists on our admiring ;

after the manner of guides everywhere,

indeed.

B u t I beg you particularly not to run

aAvay with the idea suggested by that last

phrase, that our guide was an ordinary

guide. I n some respects, no doubt, he

shared the usual characteristics of his

tribe; but his grand speciality and charm

consisted in an amount of jealous and

defiant self-sufficiency which I have never

seen equalled.

There are several categories of persons who are popularly supposed to be specially autocratic, and whoso

ipse dixit assumes an air of infallible authority ; of such are French cooks, Scotch

gardeners, and schoolmasters generally.

B u t compared with our Frascatlan cicerone—pooh, pooh, these all dAvindle Into

modest insignificance. Our man's conceit

reaches the border-land of sanity.

" Ou la vanitc va-t-elle so n i c h e r ? "

Look at the poor old fellow. H e is miserably

clad, not too abundantly fed, ignorant Avitli

the dense and stolid Iirnorance of a Roman

peasant born Avithin view of St. Peter's

iP

^^

t^-.

lot

[June 7. l!)7.l.]

ALL T H E Y E A R R O U N D .

^Conducted bi^

more than half a century ago. And yet his " Inglese, francese, italiano—tutte le lin.

faith in his own Avisdoni and acquirements gue !t "

" A h ! " exclaimed one of our party, of

is evidently all-suffieing to him. H e has got

himself uj) for Sunday in a .singular manner. a sceptical t u r n of mind, addressing him

H e has treated himself as if he Avere a frag- In Italian, " n o t much English I fancy,

ment of ancient statuary, and consisted eh ?"

cntiivl}' of torso, his head and extremities

" I speak English, yes ; but"—with a

being ignored altogether. His face Avould cunning twinkle in his eyes as he rapidly

bo almost the dirtiest object I have ever " took stock" of us to assure himself of our

seen, Avere It not that his hat is dirtier. nationality, lest he should tumble into the

But around his throat is a Avhitc shirt- pitfall of vaunting his knoAvledge of French

collar, a glimpse of clean linen is affi)rded to French people—" but—French I speak

by his wid( ly open Avaistcoat, and his coat excellently — excellently ! Gia, tutte le

has been brushed on the shoulders, and lin gue !"

down to a little below the waist. Beyond

NotAvithstanding our friend's unlimited

these points no effort at embellishment has lingual acquirements, we find It most conbeen made, either in an upAvard or down- venient to carry on our communications

ward direction. His boots look as if they with him in Italian : which language, he

were constructed of sun-dried mud, like an informs us condescendingly, he will talk

Irish cabin ; and his bands appear to have with us since we speak it well. The

been recently used as spades in the cultiva- inference, of course, being that had onr

tion of some rich soil.

Italian been a shade or two more barbarous,

Early in the proceedings his wrathful i he would have declined to allow us to consuspicions are excited by tbe production verse in it, but would have made use of

from the pocket of one of our party of the one or other of " all the other languages"

Avell-knoAvn red guide-book so familiar in which he knows.

On we go at a gentle pace, mounting

the hands of travellinor Entjlislimen. Our

cicerone eyes it askance.

H e evidently the hill, between sweet-smelling hedges of

considers Murray as his natural enemy. thickly-blossomed laurel, cyclamen, and

" H ' m , " he grunts out, with his bright " M a y " j u s t bur.sting into leaf. Wild

black eyes fixed scornfully on the red flowers of many kinds cluster in the grass

volume, " Ah, ecco !

The guide-book. beneath the hedge-rows, and the violets

Well, I have told you what there is to see embalm the air with their delicious odour.

here, haven't I ? H a ! The book. Y e s ; Owing to the number of evergreens—

oh yes. To be sure. I know it." Then laurel, bay, olive, ilex, and stone-pine—^the

with a sudden change of manner, raising landscape is not leafless, although the

bis voice to a tragic pitch, " I knoAV more deciduous trees are only budding as yet

than the book 1 I know more than the Presently we pass the iron gate leading

travellers ! ! I know more than anybody ! ! ! to a convent of Franciscan friars, and we

W h a t , I have been cicerone here for forty meet a Capuchin in his broAvn serge garb

years—more than forty years—and I don't coming down the hill. H e is a handsome,

know better than the book ? Che ! There middle-aged man, with a black beard and

is the Campagna, there is Rome, there is a blight eye. H e gives us pleasant greetthe Villa Ruffinella, Mondragone, Camal- ing, but observes smilingly on seeing that

doli, Mont' Oreste, the railway, Tivoli, one of our number is on foot, " A h a !

Monte Porzio," rattling out the names in You want yet another little donkey. Yes;

a breathless jumble, and turning round there is a somarello too few 1" I explain

as on a pivot, Avith outstretched arm, and t h a t our friend walks well, a n d prefers to

pointing finger, " don't I know them ? walk. " Aha !" cries the friar again, this

Are they in the book ?

Well, didn't time with a puzzled, incredulous look.

I tell you beforehand ? Che ! I know " He prefers to Avalk, does he ?" And

better than the book. I know better than goes on his way doAvn toward FrascatI,

anybody !"

doubtless adding one more eccentric and

incomprehensible

Englishman to the list of

Throughout the excursion we have to be

on the watch lest his susceptibilities should those whom h e has seen pass his convent

teke alarm at our appearing to know any- gates on their way to Tusctdum. To walk

thing before he tells it to us. On his first when one might ride I The t h i n g is not

introduction to us by his master, the oAvner conceivable by an Italian mind of that

of the donkeys, he slapped bis breast, a n d class.

announced that he spoke " a l l languages."

Our guide avails himself of this oppor-

^

A=

^

Chariea Di::ken8.]

MODERN ROMAN MOSAICS.

tunity to display his knowledge. " U n

cappuccino," says he in an explanatory

manner looking after the friar's retreating

figure. " A monk. They are Franciscans

in that convent. Oh, I know the monks !

I know everything. H a ! There were

pictures there

"

" Yes, a sketch by Guido," p u t s in the

sceptic, imprudently interrupting.

The guide pours out the rest of his sentence in a rush, and gives a defiant snort

at the end of It.

" U n Guide, un Giulio Romano, un

Paolo Brilli" (Paul Brill) ; " they've all

been carried away, away to Rome. Nothing

to seo there now. I know better than the

book. H ' m p h ! "

Prince Lucien Buonaparte at one time

occupied the Villa Ruffinella, which lies on

our way, and has left there a cockney reminiscence of his taste, the mention of

which ought not to be omitted from this

sketoh of a cockney holiday. There is in

the grounds of the villa a gentle slope

which the prince christened Parnassus, and

on which—to show that it was Parnassus—

he planted in box the names of various celebrated authors, ancient and modern. Our

old man stops the donkeys at this point,

throws himself into an attitude, and exdaims in a sonorous voice, " Ecco il Pernaso!" Which delicious paraphrase of

" il P a m a s s o " would have been somcAvhat

mystifying to us, had we not gleaned some

information about It beforehand from the

pages of tbe despised Murray.

A little

beyond " Il P e m a s o " stands by tbe wayside a weather-beaten, black-nosed, plaster

east on a cracked pedestal.

To this

work of art tbe cicerone calls our attention in passing, with tho announcement,

"Apollo Belvedere!" And adds after an

instant, with a sort of careless candour,

" Copia !" (a copy).

Lest AVC should

be misled into thinking that Ave saw before us the veriteble world-renowned antique :

the lord of the unerring bow,

The god of life, and poesy, and light.

Now we emerge on to a high, open down,

covered with fragrant turf.

There is a

flock of sheep on one hand, and on the other

—where the ground breaks away rather

precipitously—some goats are scrambling

among fragments of rock, and grazing on

the young sboote of the bushes. A little