A Clinical Exploration of Value Creation and Destruction in

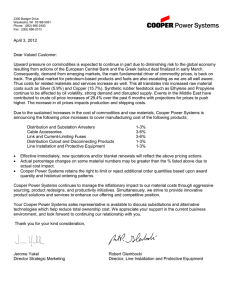

advertisement