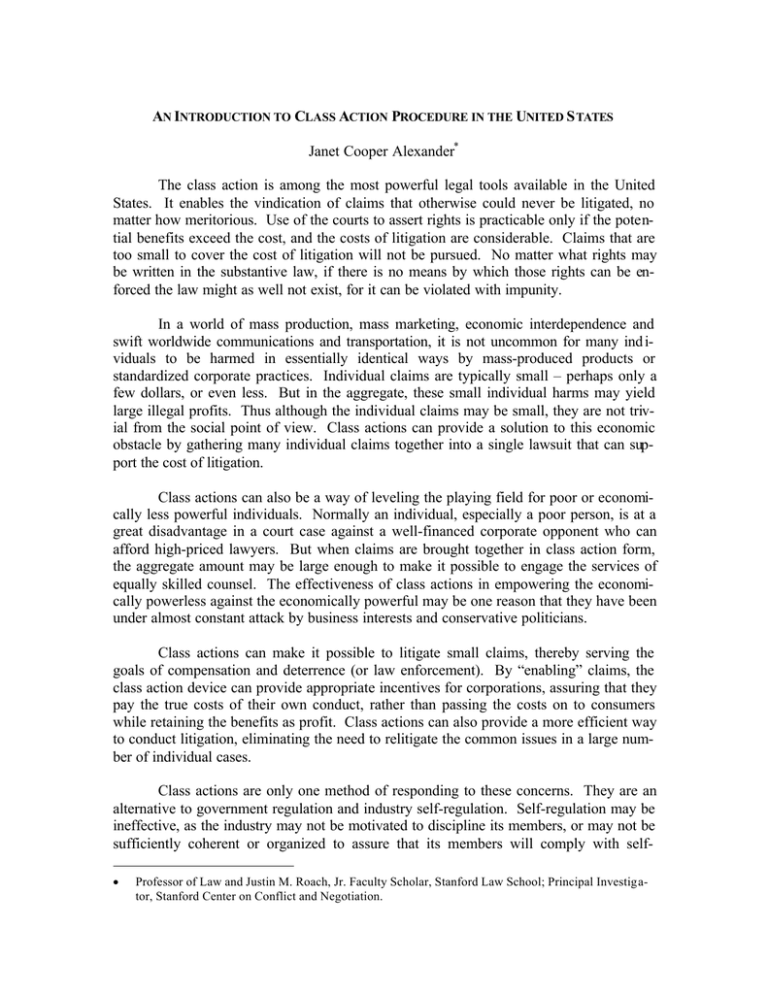

Janet Cooper Alexander The class action is among the most

advertisement