Complex Social Skills: Tools for Assessment and Progress Monitoring

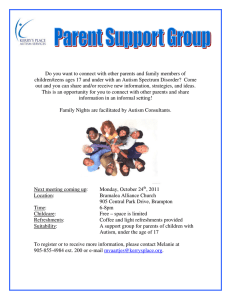

advertisement