National Framing Paper

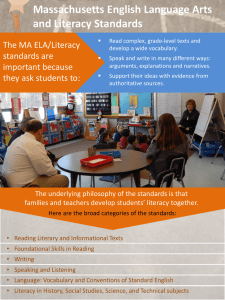

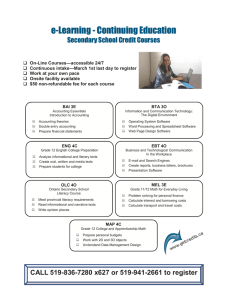

advertisement