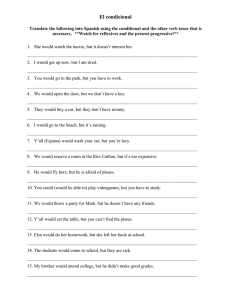

The Diamond as Big as the Ritz and Other Stories

advertisement