KOREAN L2 WRITERS` PREVIOUS WRITING EXPERIENCE: L1

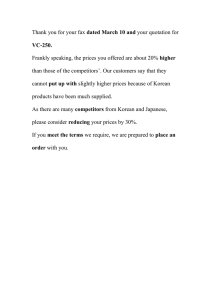

advertisement