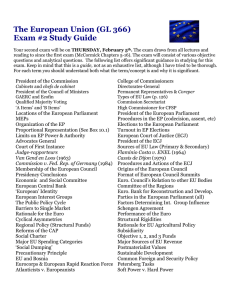

How the European Union works

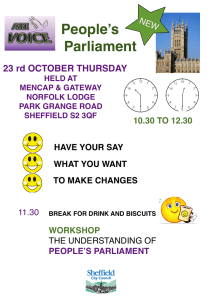

advertisement