Permitting procedures for energy infrastructure projects in the EU

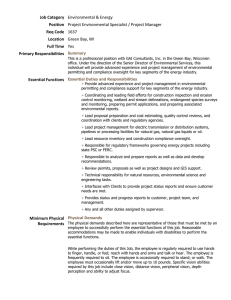

advertisement