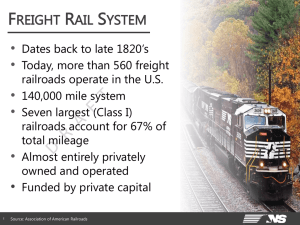

Freight Rail Transportation: Long

advertisement