Are you

in the

Mood?

It is now the office joke". Not one that all my

colleagues find amusing!

For a few years I was fortunate enough to act as

an expert assessor to a superb project funded by

the European Commission to change the lighting

LED in the Sistine Chapel* of the Vatican.

I spent months lording it up to all and sundry

about the prestige of such an engagement. The

delight of the environment and the aesthetic

impact of the project.

To maintain office harmony, I offered the next

consulting assignment to my colleague.

So when we received an enquiry from a customer

asking about lighting to create a certain ambiance for

a seductive mood, my colleague immediately

grabbed the assignment imagining that he was due to

be whisked away to Venice, the Taj Mahal or possibly

even St. Basil's Cathedral in Moscow.

Where he actually ended up was somewhat different.

Poulet Ferme in Derbyshire in fact. Yes you guessed it

a chicken farm.

A chicken farm with hundreds of squawking birds. It

transpired I misheard the request which was for

lighting to create a Productive mood

T: 01656 864618

info@lux-tsi.com

www.lux-tsi.com

(c) LUX-TSI. All rights reserved 2016

So this report is provided to you somewhat second

hand from the comfort of my office.

* Subject of a previous article

1

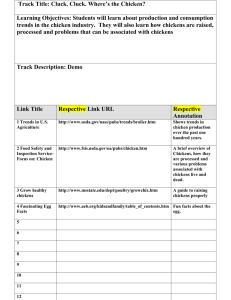

For readers of my previous column in Lux Magazine

know I have written to try to simplify much about

light. Lights in offices, lights when driving, lights

during the day, light at night, light in almost every

situation of human endeavour.

I have written about lumens, I’ve written about glare,

I’ve written about rods, cones, scotopic/ photopic

ratios. But what I have never written about was that

light suitable for humans was not necessarily good for

other creatures.

Although it’s really rather obvious. We all know about

an owls’ ability to see at night is far superior to ours or

a bees view in the black light of ultra-violet.

But what is not obvious is that the spectral sensitivity

of the eye of a chicken is far superior to ours. In fact

humans only see about 40 percent or so of what the

chicken actually sees.

Not that I want to turn this into an anatomical

lesson but it important to understand how

chickens see.

Chickens like humans have eyes comprising a

cornea and iris, which focus light onto nerve

endings in the retina at the back of the eyeball.

That’s where the similarities end as chicken’s

eyes evolved differently in four distinct ways.

First, chickens can see in the UltraViolet

spectrum. Whilst humans have tri-chromatic

vision (3 wavelengths - red, green and blue),

Chickens have tetra-chromatic (UV plus RGB).

The implications of which are astonishing. We as

humans we have no concept or experience of

what vision in this sector of the light spectrum

looks like.

Chicken eye is x25 times larger than a

human eye in proportion to head size

Everything they see looks different. We have no

description or vocabulary for how much UV is

reflected from any substance.

The 4 peaks of sensitivities of the

chicken eye.....they see UV light (grey

line), as well as all the colours we see

(c) LUX-TSI. All rights reserved 2016

2

To demonstrate this point, as far as it is possible, we

have a picture of cockatiel. Males and female

cockatiels look the same to us, but under UV light,

something else appears. The picture on the left is

human sight. The picture in the middle is the UV

spectrum only. The right hand picture is a rendering

that approximates how another bird would sense

that bird.

Second, chickens have different type of, and

different number of cones and rods. Rods enable us

to see light intensity and cones - colour. In humans

there are 2.5 rods to every cone.

Chickens have very few cones, and the ones they do

have are not especially sensitive, explaining why

chickens have poor night vision*

Left: bird and egg the way RGB eyes

see them….

Center: UV reflection of the same bird

and egg….

Right: What a chicken sees….

Bird’s colour vision is also different from ours due to

coloured filters mixed in with their nerve cells.

These are little coloured drops of oil which filter out

different wavelengths, acting in a similar manner to

wearing yellow goggles when skiing on a bright day;

the contrast is enhanced.

Imagine then wearing yellow and blue and red goggles

all at the same time. It increases contrast and brightness

and sensitivity, all at once, and we mammals can’t even

imagine what it might look like.

Third, chickens have a double cone structure in their

retina - given them a superior ability to sense

movement.

Fourth, chickens have not one but two fovea! A fovea is

a small pit in the back of retina which act as an image

enlarger.

You can see yours in action by looking at something out

of the corner of your eye, then looking at it directly in

front of you. It’s clearer in front of you. It explains why

you look slightly down at anything you are

concentrating on (the fovea is a little above the middle

of the retina).

Each of the chicken’s fovea have different jobs. One is

for seeing objects at distance; the other for objects up

close. In effect acting as built-in bifocals.

(c) LUX-TSI. All rights reserved 2016

This difference between rod to

cone ratio, and the light

sensitivities of cones in birds vs.

mammals is explained by

evolution.

When the asteroid hit our planet

mammals all but disappeared,

with those surviving being

nocturnal and insect eaters.

In the millennia that ensued,

Mammals re-developed colour

vision.

Birds, as a direct decent of

dinosaurs evolved their cones

from a different starting point

having never spent time buried

away.

3

They are also in different positions within the

cornea. The near distant one is oval shaped and

to the side. The far distant one more central.

This explains the bobbing motion of their heads.

When they get to the focal distance of about 24 feet, birds need to tilt their heads sideways to

get the image better lined up on the second

fovea.

This is what you look like to a chicken....or

at least a good guess

This explains why hens “spook” when

somebody makes a sudden movement, and why

one bird jumping from something can cause the

entire flock to take wing, even if they didn’t see

the offending stimulus.

Birds actually can’t reliably recognize flock

mates until they are within about 24 inches.

So given this biology lesson, what does it mean

for the light we need to provide to our fine

feathered friends?

Well essentially for years we got it all wrong.

Many poultry farmers today continue to do so.

Lighting using traditional incandescent or

fluorescent lighting causes large amount of

stress because the light optimized for our eyes is

not for theirs - for all the anatomical reasons

given above.

The optimal light conditions are especially hard

to achieve in poultry farming: too much light

causes stress, too little it encourages the birds to

lay eggs on the floor instead of nest boxes.

The first aspect to note is the flicker effect of

fluorescent lights. Fluorescent lights can flicker at

100-110hz and upto a few kHz – well above what

we see. But because of the combined action of

the chicken’s double cone and Fovea, this for

them is equivalent to a dance club with strobe

lights. It is exceptionally annoying. It drives them

nuts…literally.

Chickens ideally need a system operating at

50,000 hertz; with much higher frequency, there

is no risk of any flickering.

(c) LUX-TSI. All rights reserved 2016

4

The next aspect is the difficulty associated in

getting the colour is right. Chickens as

mentioned earlier see UV as well as visible light.

Under certain lighting conditions, chickens

mistake the comb on top of other chicken’s head

as food. They literally start pecking each other to

death! I mentioned earlier that chickens have

superior eyesight not intellect!

* actually even blind birds ‘see’

light.

Birds reproductive cycles are

controlled by their pineal gland,

which is located in the middle of

the bird’s forehead, just under the

skull.

Chickens need an environment where the light

spectrum that is much closer to that of sunlight

ideal for mimicking the natural influence that

daylight has on a hen's ability to produce an

egg.

The skull is thin enough that

reasonably bright light penetrates it

and will still stimulate the hormone

cascade that begins lay.

Even blind chickens can “see”

spring coming.

Chickens naturally lay eggs when they get 14

hours of light a day. So the trick is to ensure the

birds keep thinking it's spring and summer*

Armed with this knowledge and superior

‘tunable’ LED technology, such as ALIS from

Greengage Lighting, we are now in position to

deliver the right light for egg laying chickens.

Our colleague spent a wonderful time armed

with photometric meter measuring light at all

positions within the coup to ensure this was just

so. He can happily report he was not pecked

once!

Our scientists also predicted the efficacy of the

light not using the human lumen but the chicken

lumen to ensure it passed essential European

regulations.

Just remember, even if you and your

chickens can see eye-to-eye, you still won’t

see what they see.

Keep this in mind when you try to figure

out why they do what they do!

Additional contribution from:

John Matcham, Greengage Lighting Ltd

T: 01656 864618

info@lux-tsi.com

www.lux-tsi.com

(c) LUX-TSI. All rights reserved 2016

Dr Paul Miller, National Physical Laboratory (NPL)

Poultry farmer, Andrew Watson.

Mike the Chicken Vet

5