The Liquidity Dilemma and the Repo Market: A Two-Step

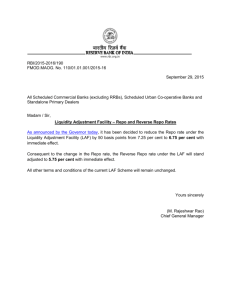

advertisement