Teaching Writing in Years 1–3 - Literacy Online

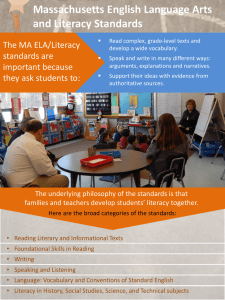

advertisement