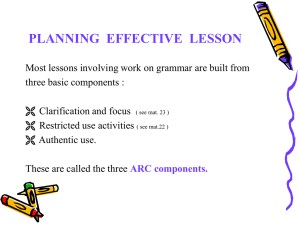

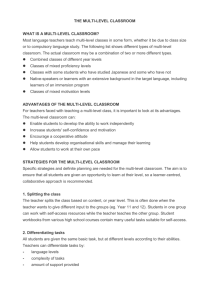

Authentic, Multi-level Teaching

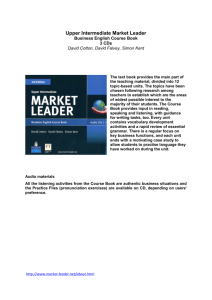

advertisement