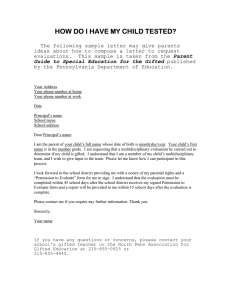

Policy and implementation strategie

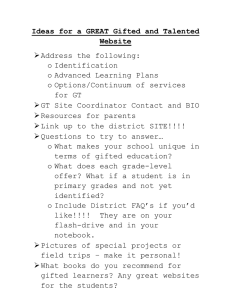

advertisement