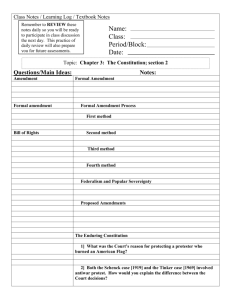

An Economic Analysis of the Constitutional Amendment Process

advertisement