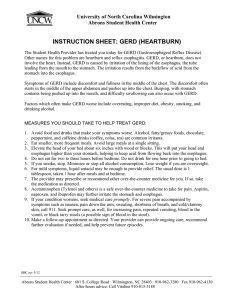

Dr Louie - Treatments for Benign Esophageal Disorders

advertisement

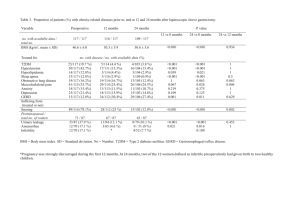

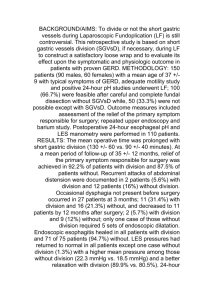

New and Emerging Treatments for Benign Esophageal Disorders Brian E. Louie MD, FACS, FRCSC, MHA, MPH Director, Thoracic Research and Education Co-Director, Minimally Invasive Thoracic Surgery Program Asst. Program Director, MIS Thoracic and Foregut Fellowships Division of Thoracic Surgery Swedish Cancer Institute and Medical Center Seattle, Washington Missoula Medical Conference September 11, 2015 Disclosures Medical Advisory Board – Torax Medical Objectives • To compare and contrast the outcomes with antireflux surgery and PPIs in the treatment of GERD • To list the newer treatment options for GERD • To review the construct and data related to magnetic sphincter augmentation (LINX) • To propose a new paradigm for GERD management What is GERD? …the passage of fluid and/or ingested material from the stomach backwards into the esophagus …normal individuals experience some GERD on a regular basis The Reflux Barrier Simple Concept • allow passage of ingested material into the stomach • prevent retrograde movement of stomach contents into the esophagus over a variety of bodily positions and pressure changes Image Courtesy of Dr. Tom DeMeester Fundamental Abnormality of GERD Loss of an effective sphincter Composition of the refluxed gastric juice Slide Courtesy of Dr. Tom DeMeester Scope of the Problem • 18.6 million Americans suffer from GERD • Nearly 10 million office visits per year • $5.8 billion in drug costs • $3.5 billion in hospital and office costs • $14.6 billion in lost productivity American Gastroenterological Association, 2001 Scope of the Problem • 40 – 50% of western populations have heartburn monthly; 10% daily • 50 million Americans have nighttime heartburn at least once per week • 65% of heartburn suffers had daytime and nighttime symptoms • 72% were taking prescription medications • 45% reported the current treatments do not relieve all of their symptoms Gallup Poll for the American Gastroenterology Association, 2003 Typical Symptoms of GERD Heartburn • Burning sensation in the upper abdomen that radiates toward the head and felt beneath the breast bone • Made worse by meals, fatty foods, caffeine containing foods • Often made better with antacids (Tums) or medications (Zantac, Prilosec) Regurgitation • Effortless return of acid or bitter stomach contents into the chest, throat or mouth • Worse when lying down, bending over • Worse with bigger meals, fatty meals • Reduced volume with medications Atypical Symptoms of GERD Respiratory Chest Pain • Chronic bronchitis • Most commonly and appropriately related to heart problems • 50% of severe chest pain with normal heart tests related to GERD • Asthma and wheezing • Also related to meal size • Bronchiectasis • Often pressure sensation • Chronic cough • Pneumonia • Pulmonary fibrosis • Difficult to define Atypical Symptoms of GERD ENT • Hoarseness • Sore or burning throat • Globus – lump in throat • Throat clearing • Trouble swallowing • Ear pain • Dysphonia Other • Dental erosions Other Symptoms of GERD • Dysphagia – the sensation that food or liquid stick or do not pass from mouth to stomach • Bloating – the sensation of fullness or distension of the upper abdomen • Nausea and Vomiting • Belching and hyperflatulence The Spectrum of GERD Type I Normal NERD Hiatal Hernia Type II Type III Healable Esophagitis Persistent Esophagitis Type IV Barrett’s Stricture (Schatzki to Fibrotic) Shortened Esophagus 2 to 16 years Adapted from Lord et al. J Gastrointest Surg 2009;13:602-610 GI Medicine Surgical Reconstruction > Utilization of PPIs and H2RA 50 45 Rate per 1000 visits 40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 GERD Dx 2000 2001 PPI Use Friedenberg et al. Digestive Disease and Science 2010; 55:1911-1917 2002 2003 H2RA Use 2004 2005 2006 Rise and fall of antireflux surgery Finks Surg Endosc (2006) 20:1698-1701 Wang and Richter Diseases of the Esophagus (2011) 24:215-23 Continued (5-Year) Followup of a Randomized Clinical Study Comparing Antireflux Surgery and Omeprazole in Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease L Lundell, MD, P Miettinen, MD, HE Myrvold, MD, SA Pedersen, MD, B Liedman, MD, JG Hatlebakk, MD, R Julkonen, MD, K Levander, MD, J Carlsson, BSc, M Lamm, BSc, IWiklund, PhD BACKGROUND: The efficacy of antireflux surgery (ARS) and proton pump inhibitor therapy in the control of gastroesophageal reflux disease is well established. A direct comparison between these therapiesis warranted to assess the benefits of respective therapies. STUDY DESIGN: There were 310 patients with erosive esophagitis enrolled in the trial. There were 155 patients randomized to continuous omeprazole therapy and 155 to open antireflux surgery, of whom 144 later had an operation. Because of various withdrawals during the study course, 122 patients originally having an antireflux operation completed the 5-year followup; the corresponding figure in the omeprazole group was 133. Symptoms, endoscopy, and quality-of-life questionnaireswere used to document clinical outcomes.Treatment failure was defined to occur if at least one of the following criteria were fulfilled: Moderate or severe heartburn or acid regurgitation during the last 7 days before the respective visit; Esophagitis of at least grade 2; Moderate or severe dysphagia or odynophagia symptoms reported in combination with mild heartburn or regurgitation; If randomized to surgery and subsequently required omeprazole for more than 8 weeks to control symptoms, or having a reoperation; If randomized to omeprazole and considered by the responsible physician to require antireflux surgery to control symptoms; If randomized to omeprazole and the patient, for any reason, preferred antireflux surgery during the course of the study. Treatment failure was the primary outcomes variable. Continued (5-Year) Followup of a Randomized Clinical Study Comparing Antireflux Surgery and Omeprazole in Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease • starting dose 20 mg, but 10% started at 40 mg/d • mostly Nissen, some partial fundos • dose escalation to 40 mg, but could go up to 60 mg Continued (12-Year) Followup of a Randomized Clinical Study Comparing Antireflux Surgery and Omeprazole in Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease • starting dose 20 mg, but 10% started at 40 mg/d • dose escalation to 40 mg, but could go up to 80 mg BUT – a gradual deteriorations in the proportion of patients in remission in both groups ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTION CLINICIAN’S CORNER Laparoscopic Antireflux Surgery vs Esomeprazole Treatment for Chronic GERD The LOTUS Randomized Clinical Trial Jean-Paul Galmiche, MD, FRCP Context Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a chronic, Jan Hatlebakk, MD, PhD Stephen Attwood, MD, PhD Christian Ell, MD, PhD Roberto Fiocca, MD, PhD Stefan Eklund, MD, PhD JAMA. 2011;305:1969-1977 relapsing disease with symptoms that have negative effects on daily life. Two treatment options are long term medication or surgery. Objective To evaluate optimized esomeprazole therapy vs standardized laparoscopic antireflux surgery (LARS) in patients with GERD. Design, Setting, and Participants The LOTUS trial, a 5-year exploratory randomized, open, parallel-group trial conducted in academic hospitals in 11 European countries between October 2001 and April 2009 among 554 patients with well established chronic GERD who initially responded to acid suppression. A total of 372 patients (esomeprazole, n=192; LARS, n=180) completed 5-year follow-up. Interventions Two hundred sixty-six patients were randomly assigned to receive esomeprazole, 20 to 40 mg/d, allowing for dose Treatment for chronic gastroesophageal reflux (GERD) = 1 Lundell et al. Clin Gastro Hep 2009 2 Galmiche et al. JAMA 2011 Continued Followup of a Randomized Clinical Study Comparing Antireflux Surgery and Omeprazole in Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Belching/Vomiting Patterns of Fundoplication Failure Richter, Clin Gastro Hep 2013 Effectiveness of PPIs for GERD • AGA sponsored telephone survey • • • • Oct – Nov 2010 N = 687/1004 on PPIs 55.3% continued to have disruptions from GERD felt like nothing else could be done to control GERD • felt it difficult to get MD to understand symptom severity Gupta and Inadomi, DDW Abstract 1154. Gastro 2012 Symptom responsiveness to acid suppression Kahrilas et al. Clinical Gastroenterology And Hepatology Vol. 10, No. 6 Impact of PPIs on # of Reflux Episodes 300 261 254 250 217 200 Total 150 100 Acid 119 98 Non-acid 50 7 0 No RX Vela et al. Gastroenterology 2001; 120:1599-1606 On PPIs Long Term Safety of PPIs C-difficile Associated Disease2 Community Acquired Pneumonia1 10 Odds Ratio Odds Ration 2 1 8 6 4 2 0 0 H2RA Use Past Use H2RA Use PPI Use Odds Ratio 3 2 1 0 PPI, < 1.75 Antibiotic use Absorption of Vitamin B124 Risk of Hip Fracture3 H2RA, H2RA, < 1.75 > 1.75 PPI Use PPI > 1.75 1. Lehaj JAMA 2004; 2. Dial, CMAJ 2006; 3. Yang, JAMA 2006 4. Corley, JAMA 2013 Recent FDA response to PPI petition Therapy Gap in GERD PPI Therapy Anti-reflux Surgery GERD PATIENT POPULATION 100% “invasiveness” durability side effects eg flatus, reproducibility Opportunity for new treatments 60% 40% <1% Satisfied with PPI Therapy Incomplete response to PPI Therapy Reflux Surgery Therapy Gap Slide Courtesy of Dr. Tom DeMeester Objectives • To compare and contrast the outcomes with antireflux surgery and PPIs in the treatment of GERD • To list the newer treatment options for GERD • To review the construct and data related to magnetic sphincter augmentation (LINX) • To propose a new paradigm for GERD management New Treatment Options Stretta • Endoscopic balloon mounted with prongs used to delivery radiofrequency energy to the GEJ • Theory: energy remodels the LES and gastric cardia and results transient LES relaxations • Neural mediated vs tissue fibrosis? Stretta • Indications: • • • • • hiatal hernia < 2 cm normal motility LESP 5 to 10 mm Hg esophagitis < LA class B no Barrett’s • Technique: • • • • EGD to measure to GEJ Catheter positioned 2 cm proximal to GEJ Inflate to place electrodes 1 min, rotate 45 degrees, repeat x 6 Stretta 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 Pre Stretta Post Stretta 50 45 40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 PreStretta PostStretta Stretta 50 45 40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 • 30% still required PPIs • 11.9% required additional treatment Pre Stretta Post Stretta • • Nissen Repeat Stretta • Minimal complications • • • chest pain dyspepsia bleeding Transoral Incisionless Fundoplication • Over the scope device • Theory: creates a partial, anterior fundoplication • Uses “H” fasteners made of permanent suture • Indications: • • • • Reducible hiatal hernia < 3 cm Hill grade II or III BMI < 35 kg/m2 No stricture, ulcer, Transoral Incisionless Fundoplication • Technique: • Complex • 2 endoscopists • Uses a “screw” to grasp tissue • Uses a “spatula” to push and hold tissue • Stylets used to pierce tissue for “H” fastener placement 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Pre TIF Post TIF Enbright et al. Annals of Thoracic Surgery 2014 Transoral Incisionless Fundoplication 40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 • 30% still required PPIs • 13.5 to 37% required additional treatment Pre TIF Pre TIF Post Post Stretta TIF • • Nissen reports of increased complications • Significant complications • • esophageal perforation bleeding Objectives • To compare and contrast the outcomes with antireflux surgery and PPIs in the treatment of GERD • To list the newer treatment options for GERD • To review the construct and data related to magnetic sphincter augmentation (LINX) • To propose a new paradigm for GERD management Sphincter Augmentation Device (LINX™ System) Titanium wire Titanium case Magnetic core Highest resistance when closed (0.39N) Roman Arch Design assures that the device is non-compressive when closed Lowest resistance when expanded (0.07N)) Shortening of LES due to gastric distension Ayazi and DeMeester. Annals of Surgery 2010;252: 57–62 Transient -LES- Shortening Distension Nissen prevents LES shortening 30 LES Length, mm 25 20 15 10 5 0 Mason, RJ et al., Arch Surg 1997; 132:719-726 0 200 400 600 800 Infused gastric volume (mL) 1000 A loose ligature prevents LES opening Samelson, Bombeck, Nyhus. Annals of Surgery (1983) 197:254 The LINX Sphincter Augmentation Device A loose ligature of expanding magnetic beads Distension Magnetic sphincter implantation Use of a magnetic sphincter for the treatment of GERD: a feasibility study Robert A. Ganz, MD, FASGE, Christopher J. Gostout, MD, FASGE, Jerry Grudem, BS, William Swanson, BS, Todd Berg, BS, Tom R. DeMeester, MD Plymouth, Rochester, Maple Grove, Minnesota, Los Angeles, California, USA Background: The success of fundoplication surgery varies widely; furthermore, complications after fundoplication can be common. We introduced a new device to treat GERD: biomechanical augmentation of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) by use of a magnetic reinforcing appliance. Objective: The aim was to determine whether a magnetic appliance could safely increase LES pressure, maintain a closed sphincter except during swallowing and belching, and increase the gastric yield pressure in a porcine model. Design: Ex vivo work-assessed design variables that would augment the reflux barrier yet still preserve swallow function. Porcine acute and chronic (44 weeks) postimplant studies were also performed. A single animal underwent planned device removal. Main Outcome Measurements: Gastric yield pressure, animal behavior, endoscopy, barium studies, balloon expansion studies, esophageal manometry, and histology. Results: Gastric yield pressure correlated with increasing magnetic forces (R2 Z 0.5608, P!.001). The sphincter augmentation device was safe in all animals, with no observed effect on eating behavior and normal weight gain. The mucosa of the esophagus appeared normal at all intervals, and there was no device migration or Ganz et al. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 67:287-97 2008 Feasibility Trials Bonavina et al. Annals of Surgery 2010 The NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL o f MEDICINE ORIGINAL ARTICLE Esophageal Sphincter Device for Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Robert A. Ganz, M.D., Jeffrey H. Peters, M.D., Santiago Horgan, M.D., Willem A. Bemelman, M.D., Ph.D., Christy M. Dunst, M.D., Steven A. Edmundowicz, M.D., John C. Lipham, M.D., James D. Luketich, M.D., W. Scott Melvin, M.D., Brant K. Oelschlager, M.D., Steven C. Schlack-Haerer, M.D., C. Daniel Smith, M.D., Christopher C. Smith, M.D., Dan Dunn, M.D., and Paul A. Taiganides, M.D. From ABSTRACT BACKGROUND Patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease who have a partial response to proton-pump inhibitors often seek alternative therapy. We evaluated the safety and effectiveness of a new magnetic device to augment the lower esophageal sphincter. METHODS We prospectively assessed 100 patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease before Ganz et al. N Engl J Med 2013;368:719-27 Components of pH Measurements Baseline No. of Median Patients Value 1 Year No. of Median Patients Value P Value pH < 4 Total %age of time Percentage of time upright Percentage of time supine 100 100 98 10.9 12.7 6.0 96 96 96 3.3 4.3 0.4 < 0.001 < 0.001 < 0.001 Total no. of reflux episodes 100 161.0 96 67 < 0.001 No. of reflux episodes lasting > 5 min 99 12.0 96 4.0 < 0.001 Longest reflux episode (min) 99 29 96 13.0 < 0.001 DeMeester score 97 36.6 96 13.5 < 0.001 Ganz et al. N Engl J Med 2013;368:719-27 Secondary Outcomes after LINX Ganz et al. N Engl J Med 2013;368:719-27 One Hundred Consecutive Patients Treated with Magnetic Sphincter Augmentation for Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: 6 Years of Clinical Experience from a Single Center Luigi Bonavina, MD, FACS, Greta Saino, MD, Davide Bona, MD, Andrea Sironi, MD, Veronica Lazzari, MD BACKGROUND: This study was undertaken to evaluate our clinical experience during a 6-year period with an implantable device that augments the lower esophageal sphincter for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). The device uses magnetic sphincter augmentation (MSA) to strengthen the antireflux barrier. STUDY DESIGN: In a single-center, prospective case series, 100 consecutive patients underwent laparoscopic MSA for GERD between March 2007 and February 2012. Clinical outcomes for each patient were tracked post implantation and compared with presurgical data for esophageal pH measurements, symptom scores, and proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use. RESULTS: Median implant duration was 3 years (range 378 days to 6 years). Median total acid exposure time was reduced from 8.0% before implant to 3.2% post implant (p < 0.001). The median GERD Health Related Quality of Life score at baseline was 16 on PPIs and 24 off PPIs and improved to a score of 2 (p < 0.001). Freedom from daily dependence on PPIs was achieved in 85% of patients. There have been no long-term complications, such as device migrations or erosions. Three patients had the device laparoscopically removed for persistent GERD, odynophagia, or dysphagia, with subsequent resolution of symptoms. CONCLUSIONS: Magnetic sphincter augmentation for GERD in clinical practice provides safe and long-term reduction of esophageal acid exposure, substantial symptom improvement, and elimination of daily PPI use. For candidates of antireflux surgery who have been carefully evaluated before surgery to confirm indication for MSA, MSA has become a standard treatment at our institution because control of reflux symptoms and pH normalization can be achieved with minimal side effects and preservation of gastric anatomy. (J Am Coll Surg 2013;-:1e9. 2013 by the American College of Surgeons) Diseases of the Esophagus (2014) ••, ••–•• DOI: 10.1111/dote.12199 Original article Safety analysis of first 1000 patients treated with magnetic sphincter augmentation for gastroesophageal reflux disease J. C. Lipham,1 P. A. Taiganides,2 B. E. Louie,3 R. A. Ganz,4 T. R. DeMeester1 1Department of Surgery, Keck Medical Center of USC, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California, Community Hospital, Mount Vernon, Ohio, 3Division of Thoracic Surgery, Swedish Medical Center and Cancer Institute, Seattle, Washington, and 4Minnesota Gastroenterology, Abbott-Northwestern Hospital, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA 2Knox SUMMARY. Antireflux surgery with a magnetic sphincter augmentation device (MSAD) restores the competency of the lower esophageal sphincter with a device rather than a tissue fundoplication. As a regulated device, safety information from the published clinical literature can be supplemented by tracking under the Safe Medical Devices Act. The aim of this study was to examine the safety profile of the MSAD in the first 1000 implanted patients. We compiled safety data from all available sources as of July 1, 2013. The analysis included intra/perioperative complications, hospital readmissions, procedure-related interventions, reoperations, and device malfunctions leading to injury or inability to complete the procedure. Over 1000 patients worldwide have been implanted with the MSAD at 82 institutions with median implant duration of 274 days. Event rates were 0.1% intra/perioperative complications, 1.3% hospital readmissions, 5.6% endoscopic dilations, and 3.4% reoperations. All reoperations were performed non-emergently for device removal, with no complications or conversion to laparotomy. The primary reason for device removal was dysphagia. No device migrations or malfunctions were reported. Erosion of the device occurred in one patient (0.1%). The safety analysis of the first 1000 patients treated with MSAD for gastroesophageal reflux disease confirms the safety of this device. Short-Term Outcomes Using Magnetic Sphincter Augmentation Versus Nissen Fundoplication for Medically Resistant Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Brian E. Louie, MD, Alexander S. Farivar, MD, Dale Shultz, BSc, Christina Brennan, CCRP, Eric Vallières, MD, and Ralph W. Aye, MD Division of Thoracic Surgery, Swedish Cancer Institute and Medical Center, Seattle, Washington Background. In 2012 the United States Food and Drug Administration approved implantation of a magnetic sphincter to augment the native reflux barrier based on single-series data. We sought to compare our initial experience with magnetic sphincter augmentation (MSA) with laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication (LNF). Methods. A retrospective case-control study was performed of consecutive patients undergoing either procedure who had chronic gastrointestinal esophageal disease (GERD) and a hiatal hernia of less than 3 cm. Results. Sixty-six patients underwent operations (34 MSA and 32 LNF). The groups were similar in reflux characteristics and hernia size. Operative time was longer for LNF (118 vs 73 min) and resulted in 1 return to the operating room and 1 readmission. Preoperative symptoms were abolished in both groups. At 6 months or longer postoperatively, scores on the Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Health Related Quality of Annals of Thoracic Surgery 2014;98:498-504 scale improved from 20.6 to 5.0 for MSA vs 22.8 to 5.1 for LNF. Postoperative DeMeester scores (14.2 vs 5.1, p [ 0.0001) and the percentage of time pH was less than 4 (4.6 vs 1.1; p [ 0.0001) were normalized in both groups but statistically different. MSA resulted in improved gassy and bloated feelings (1.32 vs 2.36; p [ 0.59) and enabled belching in 67% compared with none of the LNFs. Conclusions. MSA results in similar objective control of GERD, symptom resolution, and improved quality of life compared with LNF. MSA seems to restore a more physiologic sphincter that allows physiologic reflux, facilitates belching, and creates less bloating and flatulence. This device has the potential to allow individualized treatment of patients with GERD and increase the surgical treatment of GERD. Quality of Life QOLRAD 7 GERD-HRQL 45 25 6 LINX 20 Nissen 5 40 35 ** 30 15 4 Swallowing 25 20 10 3 15 2 5 10 1 5 0 0 Pre Op Post Post Op 6 Op 6 wks mths Pre Op Post Op 6 wks LINX: N=23/34;mean follow up 6 m Nissen: N=17/32; mean follow up 10 months Post Op 6 mths 0 Pre Post Post Op Op 6 Op 6 ** p=0.023 wks mths Objective Measures of GERD DeMeester Score 60 % time pH < 4 16 14 50 12 40 10 30 LINX Nissen 20 } 10 0 14.7 p = 0.000 8 LINX Nissen 6 4.9 4 } 2 0 Pre Op Post Op 6 mths LINX: N = 16/34; Nissen: N = 22/32 Pre Op Post Op 6 mth p = 0.000 LINX – More physiologic? Total # refluxes # refluxes - post prandial Bloating/Belching 180 100 18 160 90 16 140 80 14 70 120 104 100 LINX 80 Nisse n 60 50 40 30 40 20 20 10 0 0 Pre Op 12 60 Post Op 6 mths LINX 10 Nisse n 8 ** * p = 0.059 ** p = 0.000 6 4 * 2 Pre Op Post Op 6 mths 0 Bloat/Gas Belching Multi Institutional Outcomes Using Magnetic Sphincter Augmentation Versus Nissen Fundoplication for Chronic Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Heather F Warren, MD; Jessica L Reynolds, MD; Jody Mickley RN; John C Lipham, MD; Paul A Taiganides, MD; Joerg Zehetner, MD; Nikolai A Bildzukewicz, MD; Ralph W Aye, MD; Alexander S Farivar, MD; Brian E Louie, MD Division of Thoracic Surgery, Swedish Cancer Institute; Seattle, WA Keck Medical Center, University of Southern California, Los Angeles CA Knox Community Hospital, Mount Vernon OH Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons Nashville Tennessee April 18, 2015 Methods Antireflux Surgery (N=455) Allocation Comparative Analysis Propensity matched Magnetic Sphincter (N=201) (N=214) MSA Nissen N=169 N=185 MSA Nissen N=114 N=114 Nissen GERD-HRQL after 1 year (N=331) • MSA median follow up 12 months (0-57months) • LNF median follow up 12 months (0-58 months) 20 21 19 15 10 5 0 P < 0.01 P < 0.01 3 MSA (N=153) Baseline 4 LNF (N=178) Follow up Outcomes after 1 year (N=350) MSA N=169 NF N=185 P Value Postoperative PPI (Daily) (%) 19 14 0.18 Ability to Belch (%) 96 69 <0.01 Ability for Emesis (%) 95 43 <0.01 No Gas Bloat (%) 53 41 0.03 No Dysphagia 42 53 0.04 Propensity Matched Results (N=228) MSA NF N=114 N=114 P Value Postoperative PPI (Daily) (%) 24 12 0.02 GERD-HRQL 6 5 0.53 Ability to Belch (%) 97 66 <0.01 No Gas Bloat (%) 53 41 0.03 No Dysphagia 42 53 0.04 Patient satisfied 88 89 0.61 Would have procedure again 93 83 0.01 Objectives • To compare and contrast the outcomes with antireflux surgery and PPIs in the treatment of GERD • To list the newer treatment options for GERD • To review the construct and data related to magnetic sphincter augmentation (LINX) • To propose a new paradigm for GERD management The Spectrum of GERD Type I Normal NERD Hiatal Hernia Type II Type III Healable Esophagitis Persistent Esophagitis Type IV Barrett’s Stricture (Schatzki to Fibrotic) Shortened Esophagus 2 to 16 years Adapted from Lord et al. J Gastrointest Surg 2009;13:602-610 When you have a hammer… GI Medicine Surgical Reconstruction Indications for Antireflux Surgery • Patient wishes to control symptoms without medication • Medical therapy is no longer effective • GERD with prominent regurgitation component • Paraesophageal hiatal hernia • Complications of reflux – Esophagitis – Bleeding – Stricture – Mucosal ulceration Heitmiller and You. GERD in Cameron’s Current Surgical Therapy 10th ed, 2010 Proposed Indications for Antireflux Surgery – GI view point Vakil. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 25, 1365–1372, 2007 ACG – GERD Guidelines Katz et al. AMJG, 2013 Management Decisions by Primary Care “A patient with typical GERD symptoms experiences partial but incomplete relief with a PPI given once daily. He/she still heartburn in the late evening and at night. What 1. Increase dose or switch PPI (15%) 2. Increase dose to bid (40%) 3. Add H2RA qhs (31%) would be your preferred course of action? Chey and Inadomi. Am J of Gastro 2005 4. Refer to GI (14%) Management Decisions by Primary Care • 73% referred patient to GI before surgeon • 83% referred to surgery for lack of response to medical therapy • 11% referred to surgery b/c patient refused long term PPIs Chey and Inadomi. Am J of Gastro 2005 Indications for Surgery Surgery reserved for medical failure • erosive esophagitis • Patient wishes to control symptoms without medication • peptic esophageal ulcers • Medical therapy is no longer effective • stricture • GERD with prominent regurgitation component • Barrett’s esophagus • Paraesophageal hiatal hernia Individualized and Tailored GERD Treatment PPI Normal NERD MSA Healable Esophagitis NF Persistent Esophagitis Barrett’s Conclusions • PPIs and antireflux surgery are BOTH effective in treating GERD • PPIs and antireflux surgery BOTH have side effects and issues with durability • LINX is one of 4 new technologies for GERD that appears to control GERD and minimize side effects • The addition of LINX allows for individualized treatment of GERD New and Emerging Treatments for Benign Esophageal Disorders Brian E. Louie MD, FACS, FRCSC, MHA, MPH Director, Thoracic Research and Education Co-Director, Minimally Invasive Thoracic Surgery Program Asst. Program Director, MIS Thoracic and Foregut Fellowships Division of Thoracic Surgery Swedish Cancer Institute and Medical Center Seattle, Washington Missoula Medical Conference September 11, 2015 Swedish Digestive Health Network The Swedish Digestive Health Network provides patients and their hometown physicians seamless access to quality providers who specialize in the medical and surgical treatment of various digestive disorders. For consults, referrals and patient resources. Debra Cadiente, RN, BC Nurse Navigator digestivehealth@swedish.org 1-855-411-MYGI (6344) Fax: 206-215-3525 We believe the best outcomes can only occur when highly complex care at Swedish is supported by local expertise and knowledge.