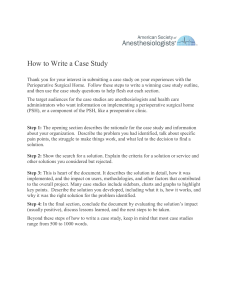

The Perioperative Surgical Home (PSH)

advertisement