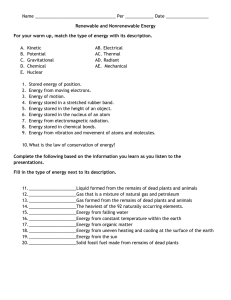

Energizing the Future - Office of the State Comptroller

advertisement