Compensation for Contractors` Home Office Overhead

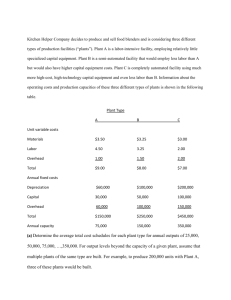

advertisement