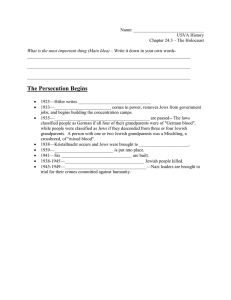

The development of the Myth of Jewish Ritual murder in England

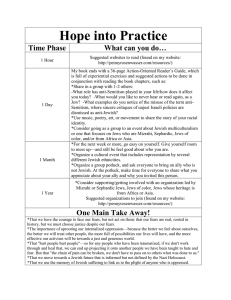

advertisement