The Criminologist - American Society of Criminology

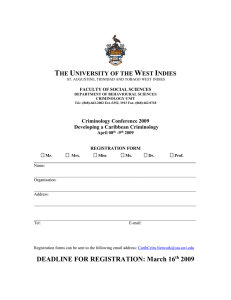

advertisement