Community-Based Health Insurance and Social

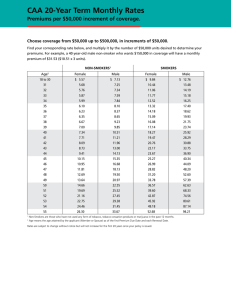

advertisement