From ordoliberalism to Keynesianism

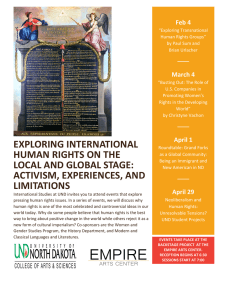

advertisement