CULTURAL POLICY AND CULTURAL DIVERSITY IN FINLAND

advertisement

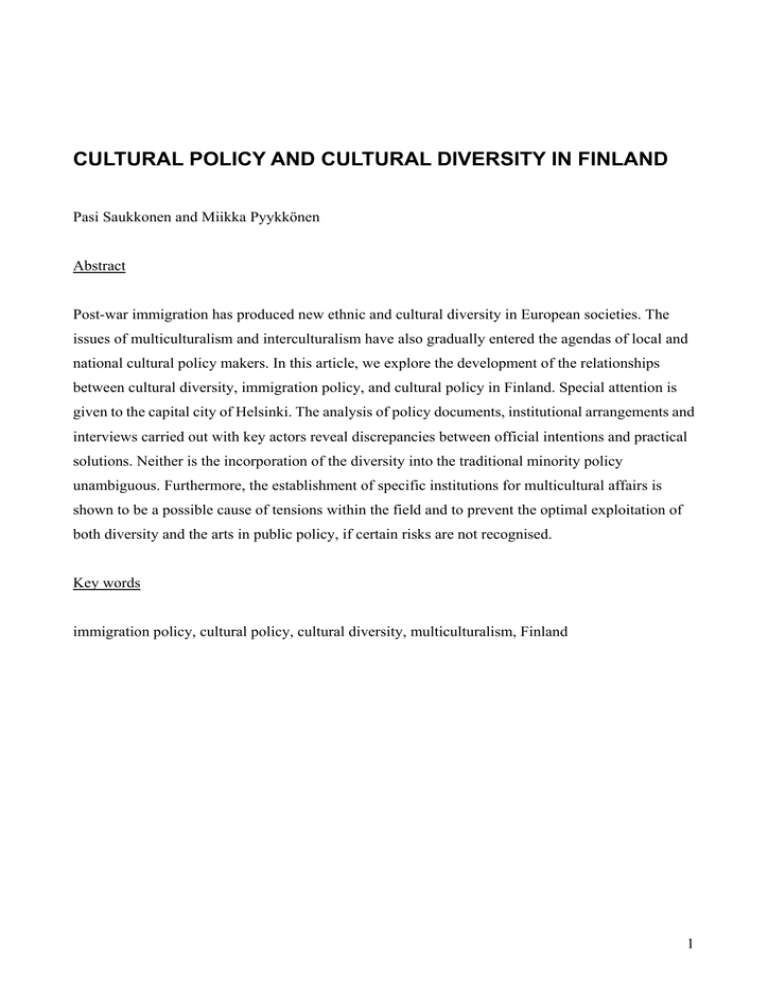

CULTURAL POLICY AND CULTURAL DIVERSITY IN FINLAND Pasi Saukkonen and Miikka Pyykkönen Abstract Post-war immigration has produced new ethnic and cultural diversity in European societies. The issues of multiculturalism and interculturalism have also gradually entered the agendas of local and national cultural policy makers. In this article, we explore the development of the relationships between cultural diversity, immigration policy, and cultural policy in Finland. Special attention is given to the capital city of Helsinki. The analysis of policy documents, institutional arrangements and interviews carried out with key actors reveal discrepancies between official intentions and practical solutions. Neither is the incorporation of the diversity into the traditional minority policy unambiguous. Furthermore, the establishment of specific institutions for multicultural affairs is shown to be a possible cause of tensions within the field and to prevent the optimal exploitation of both diversity and the arts in public policy, if certain risks are not recognised. Key words immigration policy, cultural policy, cultural diversity, multiculturalism, Finland 1 1 Introduction Ethnic and cultural diversity has become an indisputable reality in almost every European country. This “demographic multiculturalism” challenges the powerful notions of states consisting of a cultural community and of politics based on the shared values of members of the society in question. European countries, however, have relatively slowly recognised this change; this is due to the tenacious ideas of immigration as a temporary phenomenon and of immigrants as guest workers or asylum seeking refugees who will eventually return to their homelands. After the recognition of new ethnic and cultural communities as being more permanent, policy implications have been most apparent in fields directly related to the “integration” of newcomers, i.e. labour policies, education policies, social policies and housing policies. Interestingly enough, cultural policy in many countries has only relatively recently been adapted to the changing (multicultural) circumstances. However, new publications have provided evidence of the need for a change in perspective in policy making as well as in research orientations. The Council of Europe’s Cultural Committee started a transversal study on the theme of cultural policy and cultural diversity, from which three reports based on national and cross-national research have emerged (Bennett 2001; Ellmeier & Rásky 2005; Robins 2006). Several case studies have revealed the growing attention paid to ethnic and cultural diversity in national cultural policies (cf. de Jong 1999, 55-58; Skot-Hansen 2002, 201; Saukkonen 2006). The fact is that in many cases development at the national level is lagging behind what has already taken place at the local level, most obviously in large urban conglomerates where the immigrant populations are usually concentrated. Indeed, as Meinhof and Triandafyllidou point out: [C]ities provide better cognitive tools than nations for re-imagining the new interdependencies and flows in contemporary societies. They also provide empirical evidence for ways in which the possibilities arising from living with others can be seen as an opportunity for encounter rather than purely as a threat to security and dominant orders (2006, 13). 2 According to a recent study on diversity in urban cultural life, in metropolitan settings too, cultural activities aimed at culturally-diverse groups are still largely additions to the cultural landscape and there is in fact very little cultural policy proper as regards these groups and communities (Ilczuk & Raj Isar 2006, 13). However, urban studies show that there are cases where the point of contact between cultural policy and cultural diversity no longer exists exclusively in the form of political rhetoric, but has also gained some substantial practical shape (cf. Eurocult21 Stories 2005).1 2 Policy traditions, new challenges In this article, we explore the way that cultural diversity has been incorporated into cultural policy as well as the exploitation of arts and culture in Finnish immigration policy at both the national and local levels. In regard to cultural diversity, we focus on the ethnic and cultural plurality produced by immigration, which arguably poses more serious challenges to traditional cultural policies than other sources of diversity (cf. Bennett 2001, 20; for definitions of diversity e.g. Parekh 2000, 2-4; Bennett 2001, 17). The basic theoretical assumption in our approach is that the political organisation of difference has always been a central component in politics and political action (Saukkonen 2006; Koenis & Saukkonen, 2006). This is something which a nationalist assumption about the congruence between state and ethnic-cultural community has caused us to ignore. The management of plurality is thus not something that is forced upon societies by protracted ethnic conflicts, uncontrollable immigration flows or difficulties in the integration of newcomers, but, rather, something quite normal, an inherent feature of life in large human communities. Cultural policy is undoubtedly one important aspect in the political organisation of ethnic and cultural diversity. As a public policy, a cultural policy legitimises, restricts or prohibits forms of cultural self-expression, creates conditions for group-specific creative activities and self-understanding, and grants resources for specified forms of artistic and cultural activities. More symbolically, cultural policies also include and exclude forms of artistic or cultural self-expression from the recognised public sphere, constructs and maintains conceptions of normal and accepted cultural self-expression and artistic activity, and forms hierarchies between different forms of artistic or cultural self-expression (cf. Saukkonen 2006, 81). 1 Council of Europe’s and ERICarts’ Compendium of Cultural Policies and Trends in Europe (2007) is a good source for national approaches and good practices, especially the transversal issue databases on cultural diversity and intercultural dialogue. Http://www.culturalpolicies.net/web/transversal-issues.php 3 The main purpose of this article is to give a comprehensive description of the situation concerning cultural policy and migration policy and ethnic and cultural difference in the case of Finland in general and Helsinki in particular. More analytically, we shall pay attention to two distinct issues: 1) the relationship between new minorities and old minorities in a national policy context; 2) the relationship between arrangements and activities in different policy sectors in the city of Helsinki. The first research question can be formulated as follows: how do immigrants and new ethnic and cultural communities fit into the traditional cultural policy frameworks for dealing with minorities in Finland (arrow 1 in figure 1)? Every country has its own experiences of dealing with deviations from the prototype culture of the nation-state, as well as institutions for restricting or enhancing alternative forms of cultural expression. Contemporary policy solutions can either try to incorporate new forms of diversity into the established system of minority management or make a clear demarcation between traditional and new forms of diversity. In the first case, ethnic and cultural communities are not dealt with differently in respect to their historical place in society. This was for the case, for example, in the Nordic countries before specific legislation concerning immigrants was set down in 1980s and 1990s. In the latter case, there is a distinction between those “national minorities” whose cultural and political rights are considered justified and such “ethnic groups” that are presumed to assimilate or at least integrate into mainstream society in the course of time (cf. Kymlicka 1995). In Canada, for instance, there are separate laws and policy programmes for the indigenous minorities and for immigrants (Juteau et al. 1998, 98). However, in most countries features of these two models overlap in national minority policies, although there are differences in emphasises. The second research question concerns the point(s) of contact between cultural policy and cultural diversity in different sectors or pillars of public policy (see figure 1 below). On the basis of information from different national and urban settings we can expect this ”meeting” to take place in three main kinds of administrative and organisational arrangements. Firstly, the cultural needs and artistic activities of immigrants can be incorporated into the mainstream institutions and practices of cultural policy in the same way as categories such as age, gender, disability and social strata are taken into account. Secondly, the arts and culture can be integrated into the mainstream services provided for newcomers in the fields of education (e.g. artistic workshops), health care (e.g. art therapy) and social policy (e.g. sociodrama), to mention but a few. Thirdly, there can be specialised institutions for artistic multiculturalism or, as Dragan Klaic (2006, 7) says, “flagships of intercultural engagement and competence” (e.g. Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin). These institutions and arrangements 4 often combine the interests of several political and administrative sectors. In Finnish immigration and integration policy, for instance, there are influential administrative regulations stemming from the general orientations of cultural policy, integration policy and the specific orientations of cultural policy directed at the immigrant and ethnic minorities (e.g. Heiskanen & Mitchell 2002, 316-320). In the case of Helsinki, we shall look how these three sectors are related to each other in terms of cultural policy and cultural diversity (arrows 2 in figure 1). Policies concerning traditional minorities 1 Policies concerning immigrants and newcomers Mainstream cultural policy 2 Special policies and arrangements for multi- or inter-culturali sm Multi- or intercultural policy 2 Culture and the arts in the immigration policy Mainstream immigration policy Figure 1. Contact areas between cultural policy and cultural diversity The analysis is based on previous research and on a reading of the relevant policy documents. Furthermore, key actors in the city of Helsinki and an expert at the Ministry of Education were interviewed (the list of respondents appears at the end of the article) about arts and culture in the integration policy, about the role of immigrants and multiculturalism in cultural policy and about the tasks of different policy sectors. The cultural “offer” at the City of Helsinki Cultural Office in the latter part of 2006 was also analysed with specific attention to programme directed at immigrants or minority communities and to activities directly related to multi- or interculturalism. 5 In the following, we present first the national frame of reference by describing the structures of Finnish ethnic and cultural diversity, the Finnish diversity management tradition, and the Finnish migration and integration policy. Secondly, we analyse the Finnish case in two parts: the first analytic part focuses on how new forms of ethnic and cultural diversity have been integrated into Finnish cultural policy and in the second part, the City of Helsinki is taken under closer scrutiny in order to analyse and evaluate the points of contact between cultural policy, other policy sectors and cultural diversity. The main findings are drawn together in the concluding chapter. 2 Ethno-cultural diversity and diversity management in Finland The image of Finland both domestically and abroad has historically been characterised by ethnic and cultural homogeneity (Saukkonen 1999). However, despite the deeply anchored language-based “Fennoman” conception of the nation, the rights of the Swedish-speaking population were already constitutionally guaranteed at the beginning of the period of independence. The State decided to satisfy the cultural and economic needs of both the Swedish and the Finnish sections of the population, as co-founders of the nation, in accordance with the principle of equality (cf. Ristimäki 1995, 244-248). This has produced two parallel and extensive cultural infrastructures and networks of voluntary organisations within Finland (cf. McRae 1999).2 Furthermore, the Finnish Orthodox Church, with an estimated number of 60 000 members, has had the status of second national church, on a par with the Lutheran Church, since the early 20th century. As such, the Finnish understanding of national identity combines a strong sense of unity between the state and the cultural community and relatively far-reaching minority rights in legal and political practice. (Finnish minorities in table I). Minority group Swedish-speakers Sámi Roma Old Russians Tatars Jewish Total Number 295 000 7 500 10 000 5 000 800 1 400 319 700 Percentage of the whole population (5 181 115) 5,7 % 0,14 % 0,2 % 0,1 % 0,015 % 0,03 % 6,2 % Table I. The segments of traditional ethnic and cultural diversity in Finland in 20003 2 3 The autonomous status of Åland is, of course, a case apart (cf. Pesonen & Riihinen 2002, 1998-200). Sources: Heiskanen & Mitchell 2002, 308; Horn 2004; Kulonen et al. 2005; Statistics Finland 2006. 6 The Sámi and the Roma, though, were subjected to a strong policy of assimilation until the end of 1960s. The cultural rights of the Sámi have since been gradually increased. The Sámi language received official status in comprehensive schools within the Sámi domicile area in the 1980s and, in 1991, the Sámi people were officially recognised by the Finnish constitution. In 1995, a new constitutional amendment stipulated that the Sámi are an indigenous people that have the right to maintain and develop their language and culture. Cultural self-government is exercised through the Sámi Parliament, constituted in 1996. The Sámi Parliament represents the Sámi and it decides upon the allocation of money from the national budget for the benefit of Sámi culture and Sámi organisations. It may also launch initiatives, make proposals, and issue statements on matters concerning Sámi languages, culture and the status of the Sámi as an indigenous people. (Cf. Lehtola 2002.) In the 1960s, the Gypsy Association was also formed, legislation to improve social and housing conditions was put in place, and an Advisory Board of Gypsy Affairs was founded to monitor the conditions of the Roma and to make suggestions for their improvement. There have also been efforts to safeguard the Roma language since the 1980s, but its position is still relatively weak. A constitutional amendment (1995) also guaranteed the Roma rights to retain and develop their own language and culture. The Roma language has the status of a non-territorial minority language, and the Finnish government recognises the Roma community as a national minority under the European Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities. (Cf. Pulma 2006). Issues connected to these national minorities come under the remit of different ministries and policy sectors. The administration of Roma issues is mainly done in the sector of social and health affairs and in the education sector. The Advisory Board of Roma Affairs is under the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health. Issues relating to the Sámi are mostly dealt with in the department for cultural, sport and youth policy of the Ministry of Education and in the regional and local departments responsible for cultural affairs. Both The Advisory Board on Sámi Affairs and The Committee for Sámi Affairs work under the control of the Ministry of Justice (Kulonen et al. 2005, 341). One can justifiably argue that the affairs of the Sámi are thus seen as a cultural and juridical issue, whereas those of the Roma mainly as a social issue. Finland received a new Constitution in 2000 which codified earlier piecemeal changes into a single document. Some of these changes were directly related to the organisation of ethnic and cultural 7 diversity. Basic citizenship rights were stipulated as belonging to all inhabitants (earlier they were the privilege of Finnish citizens). Furthermore, article 17 of the Constitution confirms that the country’s national languages are Finnish and Swedish, and that the Sámi, as an indigenous people, as well as the Roma and other groups, have the right to maintain and develop their own language and culture. However, as Ritva Mitchell (2006, 304-305) has pointed out, what constitutes a group remains obscure. Nevertheless, we can conclude that at a time of increase in immigration, a certain tradition already existed for dealing with minorities, as did an official acceptance of ethnic and cultural diversity within the state borders. 3 Finnish migration and integration policies Until the late 1980s, immigration into Finland was at a very modest level. Since then, however, two main factors have produced greater ethnic and cultural diversity. Firstly, there was an increase in the number of refugees, especially from Somalis and the former Yugoslavia. Secondly, the repatriation policy, which allowed Ingrians from Estonia and from Russia to enter Finland as “remigrants”, produced another source of immigration. In addition, recently there also been labour-based immigration of Estonians, Russians and other nationalities. At the end of 2004, the number of foreigners in Finland was 108 346 and the number of foreign-born inhabitants 166 3614. Compared with the other Nordic countries, the percentage of newcomers in the Finnish population is still very low. Nevertheless, the change has been remarkable since 1990, when the number of foreign-born inhabitants was only 26 255. Regional differences are also great. Almost half of inhabitants with a foreign background live in the Uudenmaa province and, in Helsinki alone, the share is 18%. (Statistics Finland 2005, see table II below.) About one quarter of those inhabitants/residents with a foreign background are refugees. There is also a greater concentration in the southeastern part of Finland, where the number of people of Russian origin has been on the rise. 4 By a foreigner we mean people who live permanently in Finland without having Finnish citizenship. Foreign-born inhabitants also include those who have citizenship, but were born abroad. 8 Nation of birth Russia & Former-Soviet Union Sweden Estonia Former Yugoslavia Somalia Germany Iraq China Great Britain Thailand Whole population Foreign-born inhabitants of the whole population (%) Finland Helsinki 42,822 9,958 29,191 11,238 4,870 4,771 4,274 4,250 3,567 3,354 3,138 5 236,611 3,071 4,314 793 2,518 994 752 1,028 986 623 560,000 3,2% 5,3% Table II. Foreign-born population by country of birth at the end of 2004 (Statistics Finland 2005). Miikka Pyykkönen (2006; cf. Lepola 2000) has traced three phases in Finnish immigration policy. From 1940 until the mid-1990s, the reasons for immigration were mainly humanitarian. Immediately after the Continuation war, Finland received some 400 000 “evacuees” from the lost areas, mainly from Eastern Carelia and the Petsamo area in the North. The majority of these belonged mainly to cognate nations and ethnic groups such as the Fenno-Ugric Carelians, Ingrians, and Veps. It was thought that they would be assimilated into Finnish society without special political or administrative interventions. Immigration policy generally concentrated on the controlling of state borders. Immigration remained at a very low level, however. The second phase in Finland’s immigration policy (mid-1990s to early 2000s) is that of integration. It soon became clear that the great majority of refugees would settle in Finland without any intention of returning to their countries of origin. The Finnish answer to this development was a principle that combines the integration of individuals into society with the collective rights of communities to maintain their own culture. The main reason behind the collective cultural rights was primarily instrumental, however. Belonging to a recognised and accepted ethnic or cultural community was considered to be an asset in the integration process of the individual. The immigrant’s own culture was seen to make it easier for him or her to adopt new things and to adapt to the mainstream Finnish 9 culture (cf. Ministry of Labour 2002, 91). The new approach received legal form when the Act on the Integration of Immigrants and Reception of Asylum Seekers was approved in 1999. In the most recent phase, Finnish immigration policy has focused on labour migration. According to the Government’s Migration Policy Programme, which was approved in December 2006, integration is still the central tool for regulating immigrants’ lives once in Finland, but regulating the entrance and selection of immigrants coming into Finland has gained a lot of weight again. The administration aims to select immigrants who, above all, are believed to have the necessary qualities to succeed in the Finnish labour market after arrival. This new policy emphasises differences in administrative attitudes towards immigrants and traditional minorities, because the position of latter is not seen as a question of employment to any large extent. The labour market emphasis will most probably diminish the significance of cultural policy in the national immigration policy. However, at the local level, cultural policy might gain even more weight than it has at present. Arts and culture are seen as useful not only for individual integration into society but also as a potential arena of self-employment (Ministry of Education 2003, 27-33). 4 Finnish cultural policy and diversity The history of Finnish cultural policy has often been divided into three periods (cf. Heiskanen 1995; Kangas 1999). The first period, from the 1860s to the 1960s, was marked by ambitions to strengthen the cultural identity of the Grand Duchy and later of the independent state. This goal was also reflected in the central government’s policies to promote the arts and to support artists. In the 1960s, cultural policy was transformed from an instrument of nation-building into an articulated policy sector of the welfare state. In the 1990s, in turn, the strong role of the state and municipalities in cultural policy-making was diminished because of both ideological and economic reasons. As in many other countries, the incentive to maintain and enhance national culture and identity was transformed rather than being totally abandoned. The cultural policy of the Finnish Ministry of Education embraces creativity, the status of artists, the network of regional cultural services, multiculturalism, international co-operation, and cultural exportation. There is no particular division at the Ministry for issues concerning ethno-cultural diversity, instead matters relating to multiculturalism and access to culture come under different units and departments. A unit that is responsible for the development of Swedish-language education and culture functions directly under the Permanent Secretary. For Sámi and Roma affairs there are no 10 separate secretaries or bodies, but there is a policy group for immigration, minorities, and human rights affairs (the Finnish acronym is MAVI), which deals with them on a case-specific basis (Cortes-Tellez 2006). Concerning immigration and immigrants, the Ministry of Education quite logically deals with affairs related to education, research, sports, young people and culture. Culture-related terminology unsurprisingly appears in abundance also in the discourses of other involved ministries.5 Usually, however, “culture” refers to the whole way of life of individuals and groups, or it is simply used as a synonym for ethnicity or different background. At the Ministry of Education, “culture” more specifically denotes arts and creativity. The Ministry of Education has recently established its own principles for supporting groups that represent minority cultures and civic activities which increase tolerance (Ministry of Education 2003). In this document, the Ministry follows the Finnish government’s earlier decision on the basic premises for immigration and refugee policy-making which states that cultural minority groups include both ethnic and linguistic minorities and refugees and immigrants without distinction. This implies that immigrants are incorporated into the historically evolved minority policy.6 There is also a clear commitment to collective minority rights when, for example, financial support is granted for the preservation of minority cultures and identities. In a strikingly tolerant tone, cultural minorities are given the right to choose how they will maintain their own cultural identity. Public authorities, in turn, have to accept the self-expressed value order of traditional ways and forms in a minority culture. A certain ambiguity between “supporting culture and identity for its own sake”, so to speak, and “supporting culture and identity for the sake of smooth integration into society” is apparent again, however. The objective of Finnish integration policy, the “flexible and efficient integration into society” allows for both interpretations. Cultural services and support for culture are, among other activities, considered very important for the integration of immigrants. The purpose behind supporting cultural minority groups is, then, to strengthen the positive adaptation of these groups into society and to thus create opportunities to use general cultural services and forms of support. 5 The Ministry of Foreign Affairs regulates international co-operation and visa-policy. The Ministry of the Interior is responsible for immigration and emigration and for citizenship applications. The Ministry of Labour is responsible for the reception of asylum seekers, migrants and refugees, integration of all immigrants, and labour issues. Furthermore, it co-ordinates cross-sectoral work for good ethnic relations. 6 In its definition of cultural minorities, the Ministry of Education includes, firstly, traditional minorities such as the Swedish-speakers and the indigenous Sami people, secondly, other minorities as the Roma, Russian-speakers and the 11 Furthermore, in the more concrete part of the document, the emphasis is placed on individuals rather than groups, as immigrants are mentioned as users of cultural services and as immigrant artists. All in all cultural policy objectives concerning immigration sound quite sublime. However, accomplishments in reality are still lagging behind. In their policy analysis, Ilkka Heiskanen and Ritva Mitchell conclude that the otherwise positive development concerning the cultural rights of minorities has been less apparent in the case of immigrants. Despite the in-principal opportunities for maintaining and developing a person’s/group’s own culture and language, in the carrying out of actions, “the emphasis has (naturally) been on labour and education policy measures, and on the prevention of prejudice and racism, not so much on the opportunities for immigrants to affect cultural participation and the development of their cultures.” (Heiskanen & Mitchell 2002, 318-319.) Nonetheless, the authors also argue that the most important work in the development of cultural services, in the promotion of cultural participation, and in the improvement of working conditions for immigrant artists takes place at the municipal level (ibid, 320-321). Therefore, we shall also turn to an analysis of a local solution to cultural diversity in cultural policy. 5 The Helsinki case The national legal and programmatic framework has clearly influenced local policies concerning immigration and multiculturalism. The Finnish Act on the Integration of Immigrants and Reception of Refugees, for example, soon brought about local integration programmes. In Helsinki, this programme was accepted already in 1999. There is, however, ample room for manoeuvre for municipalities to follow their own course of action in future initiatives and practical arrangements. This means that municipalities are free to a certain degree to decide how they will fulfil national demands for integration in practice. In fact, Helsinki has in many issues relating to immigration and multiculturalism been some steps ahead of national policy development. In 1991, a working group had already expressed its objective as the development of Helsinki into an international, multicultural capital where foreigners have equal rights to municipal services and the opportunity to integrate while maintaining their own linguistic and cultural background (Joronen 2003, 13). According to Mervi Perkinen (1997, 110), the Tatars, and thirdly, more recent immigrant groups. Furthermore, different disability groups, religious communities, sexual minorities and certain age groups (notably young people) are mentioned as having specific cultural characteristics. 12 city’s immigration policy represented a culturally plural or multiculturalist approach in which the special cultural characteristics of minorities should be taken into account in welfare policies for minorities.7 Besides championing cultural plurality, more instrumental values are again obvious. As was later to become the cornerstone of national policy, a strong ethnic community was considered a means to help integration into Finnish society. The associations to which the immigrants belonged were seen as good instruments in the rallying of their own interests and in the strengthening of members’ personal identities. This, in turn, was seen as an asset in societal integration (cf. Joronen 2003, 15; Pyykkönen 2007). The city of Helsinki applied the same approach as the Finnish state, which incorporates immigrants’ services into the existing sectoral system. In the provision of services, the educational, social and health issues, and services of immigrants were dealt with in the respective institutions (education department, social services department, health centre) (Joronen 2003, 24-25). The most notable exception to this rule was the establishment of the International Cultural Centre, Caisa. This institution deserves special attention as it is directly related to our second research question on the relation of different sectors and the position of cross-sectoral arrangements. 5.1 Multicultural centre in crisis Caisa was founded in 1996 to enhance the contact between the Finnish inhabitants of Helsinki and immigrant groups, to provide for services that give relief to acute everyday problems, and to promote the emergence of a multicultural Helsinki (Joronen 2003, 13-14). Ethnic and cultural diversity played a central role in the image of a European city with a strong cultural identity, a role which at the time Helsinki was striving for. This was one of the reasons why cultural activities for and by newcomers were considered as issues that required strong support. This idea, obviously along with the terminological congruence between cultural policy and multiculturalism, was the reason that Caisa was located within the City of Helsinki Cultural Office (see figure 2 below)8. There were also direct references to the need to reorganise and to relocate the 7 Helsinki is actually one of the very few bilingual capital cities in Europe. The Cultural Office is an administrative body of the City of Helsinki, established “to foster an encouraging atmosphere and a climate suitable for producing and experiencing art and culture in Helsinki” [see 8 13 cultural “offer” of the city and to promote the public display of immigrant artists’ work and capabilities. Furthermore, there was a wish to emphasise that immigrant issues are not the concern of social policy alone (ibid. 14, 99). However, it seems that the leadership of the Cultural Office was not well enough informed at the time of Caisa’s establishment, and that the unit had to accept the new situation relatively unprepared and inexperienced (ibid. 99). This was probably one reason for the problems that produced a minor crisis after a few years. When Caisa was evaluated in 2002 by Tuula Joronen, the response from interviewees – those involved in (making) both cultural policy and immigrant policy – revealed the delicate position of an institution that combines the interests of several administrative sectors. Figure 2. City of Helsinki Cultural Office Organisation. Source: Silvanto 2005, 134. http://kulttuuri.hel.fi/vuosikertomus05/main_en.php]. The Cultural Office has recently been reorganised which means that figure 2 does not properly reflect the contemporary situation. 14 The then director of the Cultural Office had publicly questioned the original idea behind Caisa by arguing that work related to the integration of immigrants did not come under the remit of his department. Rather, he maintained, it was the responsibility of the department of social affairs, education and youth work (cf. Joronen 2003, 99). It is obvious that many of Caisa’s activities, such as Finnish language lessons, consultation services, computer courses, and the management of an immigrant associations’ network, did not match the Cultural Office staff’s idea of cultural activities. Even the more artistic activities were not always considered “fine enough” to qualify as cultural activities, as the interviews carried out for this study indicated. The situation turned out to be quite extraordinary. On the one hand, the different sub-units in the Cultural Office had almost no co-operation with Caisa. On the other hand, Caisa was evaluated in a strikingly positive way by those city units and departments that had been in close contact with it, i.e. the unit for immigrant services of the City of Helsinki Social Department and the City of Helsinki Education Department (ibid. 88). The struggle for scarce economic resources apparently also played a role in this process. There was also more academic criticism towards Caisa’s multicultural orientation: Mia Toikka (2001) argued that encounters between Finns and immigrants, and the interaction between different groups are less frequent and more superficial than supposed. Furthermore, she claimed that Caisa mainly promoted a message of “celebrating multiculturalism” in which cultures were represented through exotic artefacts without creating enduring social bonds between individuals and groups. Joronen’s user research gives the same results in part, but she emphasises that there is more interaction than Toikka’s research shows (Joronen 2003, 56-60). Moreover, Joronen’s (ibid. 53) research also revealed that over a half of Caisa’s visitors and users were of “Finnish” background and over two thirds of them were women. 5.2 Cultural landscape and cultural diversity The position and profile of Caisa seems to no longer be disputed. Even though the activities of the Centre still encompass much more than arts and culture in a strict sense, it seems that the more traditional cultural activities in the Centre have, relatively speaking, increased in the larger venue into which Caisa later moved. The new director of the Cultural Office has also clearly expressed a broader understanding of “culture” than his predecessor. There are, however, still opinions in the field which suggest that the Cultural Centre is not ”visible enough” in the different areas of the city. Because 15 Caisa is located in the very centre of the city, the question has also been raised whether the cultural centre reaches the different immigrant communities in an equal manner. An analysis of multicultural services offered by the Cultural Office in the latter part of 2006 shows that Caisa still occupies a very prominent role in activities that combine arts, culture and new ethnic diversity.9 Other sub-units of the Cultural Office also have international programme and organise multicultural activities (Silvanto 2005, 138), but these activities either seem to be unrelated to the new ethnic and cultural communities or are otherwise quite sporadic in nature. The Savoy Theatre, for example, is the forum for world music, yet visits to Finland by famous stars is connected with the Cultural Office’s objective of internationalism rather than with the local structures of ethnic and cultural diversity.10 At the cultural centre Stoa, located in the eastern part of the city, where the proportion of immigrants is highest, special multicultural events are organised. However, in the autumn of 2006, for example, there were only four such events.11 There are some particular details that reveal the discrepancy between multiculturalism in theory and in practice. The contemporary Finnish folk music event “Etno-Espa” at the Cultural Office’s Espa stage, for example, did not present the music of newcomers at all in 2006.12 According to the event homepage, “The concept of ethnicity normally refers to something strange, to the other. What is strange to us, however, is familiar to others, and what is familiar to us, is strange to others. The objective of Etno-Espa is to present to Finns as well as to tourists urbanised music that has been influenced by other cultures, but which draws from our own ethnic background, music that is our etno.”13 In spite of the idea of cultural mixing implicit in this thought, the statement above underlines the distinction between “us” and “them”. Obviously, it will take time before the traditional or neo-traditional music of immigrants can be considered as ”our etno”. 9 The centre also has a strong position in the administration of immigrant policy. It is often people connected to Caisa that participate, for example, in municipal and cross-municipal organisations such as the “The City of Helsinki Advisory Board on Immigration and Integration”. 10 Events which present Russian music or theatre can, however, be mentioned as a deviation from the rule because they frequently bring lots of people of Russian origin to the audience. 11 “Celebrating multiculturalism” was quite prominent in these events. According to the unit’s programme, “Colourful East” featured, amongst other things, Indonesian and Thai dancing, Greek music, an ethnic fashion show, a salsa performance and workshop, young Eastern Helsinki bands, a Somali handicraft workshop, a Russian puppet theatre for children, and flavours from all over the world. Furthermore, an exhibition of Chinese Porcelain Art combined lectures and music. “Beauty Speaks: Africa” contained a performance of dance, theatre, song, and rhythm featuring artists from many different cultures. The “Chinese Folk Art and Handicraft” event displayed over a hundred items from different parts and nationalities of China. 12 The famous Sámi musician, Wimme Saari, was among the performers, though. 13 The Etno Espa home page is at http://www.etno-espa.com/etnoespa2.html (translation P.S.) 16 On the basis of available information, it seems plausible that the cultural dimension (in the sense of arts and creativity) is still very narrowly exploited in social, health and educational work connected with immigrants and their descendants. A recent survey of immigrant projects (Ruhanen & Martikainen 2006, 67-69), for example, reveals that very few of them focus on the arts or culture. The almost sole actor in this field is the arts association Kassandra, whose Moninaiset project, for example, aims at improving the standards of living in certain areas by providing the possibility of free art workshops, lectures and art events for women of all backgrounds. There are, however, some indicators that creative approaches in immigrant work is on the increase and that the practices used in Caisa have now been adopted in other areas of municipal policy. A cultural producer with multicultural work as his main responsibility was also recently appointed to the cultural centre, Stoa, in Eastern Helsinki. 5.3 Lessons from the local level There is no doubt that Caisa has been a successful institution in many respects. It functions as a “home” for a large range of activities that bring together members of the mainstream or dominant culture and those from minorities and immigrant communities. In the spirit of the Integration Act and local integration programmes, Caisa provides newcomers with facilities intended both for assisting integration into Finnish society and for the maintenance of immigrants’ own ethnic and cultural community/ies. Finally, the premises for associations, art galleries, courses in the arts and craftsmanship and other available facilities support both individual and collective artistic self-expression and development. Nonetheless, the Caisa case also reveals the tensions and problems inherent in the creation of such a specialised centre for multicultural affairs. First or all, we can observe a terminological ”clash of cultures” when the similarity of meaning of ”culture” in cultural policy and in multiculturalism (or cultural diversity) is taken for granted even though the central actors have their own highly divergent interpretations. Secondly, this kind of a sector-crossing organisation can easily become an object of criticism from sector specialists who may think that those in the special unit deal too much with that and do not know enough about this. These suspicions and prejudices can easily be aggravated by the struggle for scarce resources. Finally, there is a danger of producing a “lazy mentality” where actors avoid taking responsibility for independent action by reasoning that ”now that we have the multicultural centre we do not have to do it ourselves”. 17 The most important issue here concerns the role of different organisational arrangements in the construction of a diverse society. For the sake of argument, we can point out two possible scenarios. In the positive scenario, good practices in the multicultural centre are followed by other units in other administrative sectors. In this way, cultural sensitivity is incorporated into normal services and immigrants and their communities are taken into account in the mainstream cultural policy. The multicultural centre would then function as a meeting point that is accessible to all and one that provides the public with interesting programme. Subsequently, creative solutions using the arts and culture are applied in immigrant services. This scenario results in a situation where ethnic and cultural diversity is considered as a normal feature of urban life. Despite all differences among the population, there is still enough unity to hold society together and to maintain mutual solidarity. In the negative scenario, the centre becomes an isolated multicultural universe, ”a reservation” within a society that otherwise refuses to accept the diversification of social realities. At the programmatic level, the cultural rights of new members of the society and those of the more traditional minorities are dealt with together; in practice, the right for public support in maintaining one’s own cultural identity may turn out to be lip service without true support or financial subsidies. Activities related to the arts and culture and the new immigrants can then be restricted to special institutions and forums which the majority of the population seldom or never enter. Individuals, groups and communities that have found their way to the multicultural centre and its services – or otherwise have enough resources – have their needs relatively well satisfied. Those that are, for one reason or another, outside the range of the support systems, will lack facilities, resources, audience and public recognition. In this situation, there is a risk of polarisation between those who subscribe to the idea of cultural homogeneity and those who, after long periods of residence, still feel that they are not welcome. 6 Conclusion The analysis above does not, of course, allow for any far-reaching generalisations. The challenges of incorporating newcomers into the scope of traditional minority policies and cultural policies and of finding a good balance and working co-operation between different policy sectors concerning immigrants and their descendants are, however, central political issues in many European countries and in numerous local communities. Therefore, the Finnish findings can be used, for example, as hypotheses in the description, analysis and evaluation of other cases. 18 Firstly, the Finnish case emphasises the need to analyse not only programmatic discourse at the national level but also practical arrangements and solutions at the local level. It is obvious that there is often less real activity than programmes promise. In addition, there can be clear discrepancies between what is endeavoured in principle and what is really done. Even though the Finnish official integration policy guarantees the right to maintain and develop one’s own culture and religion in accordance with Finnish law, in practice resources for the latter are not sufficient for cultural self-development. In fact, as Ritva Mitchell (2006, 305) has pointed out, the formulation of the Finnish integration policy already indicates that culture (and cultural policy) is in a problematic and secondary position compared with general welfare (and welfare policy). In many cases, the cultural identity of immigrants is not valued as an independent phenomenon in and of itself, but rather as an instrument for achieving/facilitating societal integration. Concerning our second research question, our analysis suggests that there remains a clear line of demarcation between ”traditional minorities” and ”new minorities”, even though in the “diversity policy discourse” these are often dealt with as one issue. Theoretically, this is of course completely congruent with the standpoint of Will Kymlicka (1995), for example. For Kymlicka, new ethnic groups formed by voluntary migration simply do not have the same rights as traditional minorities with their societal cultures. Research, however, has indicated that many immigrant groups maintain their cultures and identities in the long-term, and, for instance, organise themselves in compliance with them, even though their cultural rights are not guaranteed to the same level as are those of traditional minorities (e.g. Rex et al. 1987; Wahlbeck 1999). Their inclusion in mainstream cultural policy, then is also a question of general equality and inclusion. It would at least be fair for new communities to know whether they can expect public recognition for their own culture in the future or if cultural rights are to remain primarily in the private sphere. Our third research objective was to look at the points of contact between cultural policy and cultural diversity in three policy sectors or pillars: in mainstream cultural policy, in mainstream immigrant policy, and in special multi- or intercultural policy. The cultural centre Caisa is a relatively successful example of the lattermost alternative. Nonetheless, Dragan Klaic (2006, 7) has remarked that there is a danger that such flagship institutions remain “cordoned off, accepted or ‘tolerated’ as a ghetto, single or multiple, doesn’t matter much, deprived of any impact by benign neglect.” Our analysis confirms that such perils are realistic. These institutions can hamper positive developments in respect to the incorporation of both a cultural policy and diversity perspective into the mainstream urban and community development if the risks inherent are not properly recognised. 19 It is difficult to say what the best way of organising the convergence of cultural policy and cultural diversity might be. Undoubtedly due attention has to be paid to the political context in question, with its own histories, traditions, trajectories, concepts, ideologies and structures of ethnic and cultural diversity (cf. Bennett 2001, 23). Nevertheless, there seems to be sound reasons to expect that all of the three sectors or pillars discussed in this article should be exploited to some extent in order to translate the change in ethnic and cultural structures into political action and to avoid leaving important methods and resources unused. New ethnic and cultural minorities should be incorporated into mainstream cultural policy, which should then reflect the structural realities of society. Arts and culture should be more broadly used in immigrant work because there are numerous examples of how creative methods can be efficiently exploited in therapeutic work, in preventing social marginalisation and conflicts, in increasing tolerance and cross-cultural contacts, as well as in the positive hybridisation of identities. Finally, there is certainly a need for multi- and intercultural centres that provide facilities for artistic and cultural activities within immigrant groups and, possibly even more importantly, in an inter- and cross-cultural context. Bibliography Bennett, Tony (2001) Differing Diversities: Transversal Study on the Theme of Cultural Policy and Cultural Diversity (Council of Europe Publishing, London). Ellmeier, Andrea and Rásky, Béla (2005) Differing diversities: Eastern European Perspectives (Council of Europe, Strasbourg). Eurocult21 Stories (2004) (City of Helsinki Cultural Office, Helsinki). Heiskanen, Ilkka (1995) “Development of Finnish Cultural Policy: an Outline”, In: Cultural Policy in Finland: National Report (The Arts Council of Finland, Research and Information Unit, Helsinki), pp. 27-68. Heiskanen, Ilkka and Mitchell, Ritva (2002) ”Kulttuurivähemmistöt, monikulttuurisuus ja kulttuurioikeudet”, In: Heiskanen, I., Kangas, A. and Mitchell, R., eds., Taiteen ja kulttuurin kentät: perusrakenteet, hallinta, lainsäädäntö ja uudet haasteet, (Tietosanoma, Helsinki), pp. 303-326. 20 Horn, Frank (2004) National Minorities of Finland. <http://virtual.finland.fi/netcomm/news/showarticle.asp?intNWSAID=26470> 1.2.2006 Ilczuk, Dorotha & Raj Isar, Yudhisthir, eds. (2006) Metropolises of Europe. Diversity in Urban Cultural Life (CIRCLE, Warsaw). Jasinskaja-Lahti, Inga, Liebkind, Karmela & Vesala, Tiina (2002) Rasismi ja syrjintä Suomessa. Maahanmuuttajien kokemuksia (Gaudeamus, Helsinki). Jong, Joop de (1999) ”Kulttuurinen monimuotoisuus ja kulttuuripolitiikka Hollannissa”, In: Kangas, A. & Virkki, J., eds, Kulttuuripolitiikan uudet vaatteet (SoPhi, Jyväskylä), pp. 49-72. Joronen, Tuula (2003) Helsingin ulkomaalaispolitiikan teoria ja käytäntö. Helsingin kaupungin tietokeskuksen verkkojulkaisuja 2003: 17 (Helsingin kaupungin tietokeskus, Helsinki). Juteau, Danielle et al (1998) ”Multiculturalism à la Canadian and Intégration à la Québécoise. Transcending their Limits", In Bauböck, R. & Rundell, J., eds, Blurred Boundaries: Migration, Ethnicity, Citizenship (Ashgate, Aldershot), pp. 95-110. Kangas, Anita (1999) ”Kulttuuripolitiikan uudet vaatteet”, In: Kangas, A. & Virkki, J., eds, Kulttuuripolitiikan uudet vaatteet (SoPhi, Jyväskylä), pp. 156-178. Klaic, Dragan (2006) “Cultural policies and institutions facing the challenge of multicultural societies”, In: Quando la cultura fa la diferenza, Patrimonio, arti e media nella societa multicultureale, eds., Bodo, S & Cifarelli, R. (Roma), 90-102. Koenis, Sjaak & Saukkonen, Pasi (2006) “The Political Organization of Cultural Difference”, Finnish Journal of Ethnicity and Migration 1, 4-14. Kulonen, Ulla-Maija, Seurujärvi-Kari, Irja & Pulkkinen, Risto (2005) The Saami: a Cultural Encyclopaedia (SKS, Helsinki). Kymlicka, Will (ed.) (1995) The Rights of Minority Cultures (Oxford University Press, Oxford). 21 Lehtola, Veli-Pekka (2002) The Sámi People: Traditions in Transition (Kustannus-Puntsi, Inari). Lepola, Outi (2000) Ulkomaalaisesta suomenmaalaiseksi: monikulttuurisuus, kansalaisuus ja suomalaisuus 1990-luvun maahanmuuttopoliittisessa keskustelussa (SKS, Helsinki). McRae, Kenneth D. (1999) Conflict and Compromise in Multilingual Societies: Finland (Finnish Academy of Science and Letters, Helsinki). Meinhof, Ulrike Hanna and Triandafyllidou, Anna, eds. (2006) Transcultural Europe: Cultural Policy in a Changing Europe (Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke). Ministry of Labour (2002) Valtioneuvoston selonteko kotouttamislain toimeenpanosta (Ministry of Labour, Helsinki). Mitchell, Ritva (2006) “The promotion of cultural diversity through integration policies in Helsinki”, In: Ilczuk, Dorotha & Raj Isar, Yudhisthir, eds. (2006) Metropolises of Europe. Diversity in Urban Cultural Life (CIRCLE, Warsaw), pp 296-315. Ministry of Education (2003) Opetusministeriön maahanmuuttopoliittiset linjaukset (2003) Opetusministeriön työryhmämuistioita ja selvityksiä 2003:7 (Ministry of Education, Helsinki). Parekh, Bhikhu (2000) Rethinking Multiculturalism. Cultural Diversity and Political Theory (Macmillan, Houndmills). Perkinen, Mervi (1997) ”Helsingin ulkomaalaispoliittinen ohjelma arvioinnin kohteena”, In: Schulman, H. and Kanninen, V., eds, Sovussa vai syrjässä? Ulkomaalaisten integroituminen Helsinkiin. Helsingin kaupungin tietokeskuksen tutkimuksia 1997:12 (Helsingin kaupungin tietokeskus, Helsinki), pp. 109-121. Pesonen, Pertti and Riihinen, Olavi (2002) Dynamic Finland: the Political System and the Welfare State (Finnish Literature Society, Helsinki). Pulma, Panu (2006) Suljetut ovet: pohjoismainen romanipolitiikka 1500-luvulta EU-aikaan. Helsinki: SKS. 22 Pyykkönen, Miikka (2006) “Maahanmuuttopolitiikan (moni)kulttuuriset vaikutukset”, In: Häyrynen, S., eds, Kulttuurin arviointi ja vaikutusten väylät (CUPORE, Helsinki). Pyykkönen, Miikka (2007, forthcoming) “Integrating Governmentality. Administrative Expectations for Immigrant Associations in the Integration of Immigrants in Finland”, Alternatives. Rex, John et al. (eds.) (1987) Immigrant Associations in Europe. Aldershot: Gower. Ristimäki, Eija (1995) “Minorities and Cultural Rights”, In: Cultural Policy in Finland National Report (The Arts Council of Finland, Research and Information Unit, Helsinki), pp. 241-256. Robins, Kevin (2006) The Challenge of Transcultural Diversities: Cultural Policy and Cultural Diversity (Council of Europe, Strasbourg). Ruhanen, Milla and Martikainen, Tuomas (2006) Maahanmuuttajaprojektit: hankkeet ja hyvät käytännöt. Väestöntutkimuslaitoksen katsauksia E22/2006 (Väestöliitto, Helsinki). Saukkonen, Pasi (1999) Suomi, Alankomaat ja kansallisvaltion identiteettipolitiikka. Tutkimus kansallisen identiteetin poliittisuudesta, empiirinen sovellutus suomalaisiin ja hollantilaisiin teksteihin (SKS, Helsinki). Saukkonen, Pasi (2003) “The Political Organization of Difference”, Finnish Yearbook of Political Though (SoPhi; Jyväskylä). Saukkonen, Pasi (2006) “From the promotion of national identity to the management of plurality: cultural policy developments in Belgium (Flanders), Finland and the Netherlands”, Nordisk Kulturpolitisk Tidskrift 2. Silvanto, Satu (2005) “City of Helsinki”, In: Eurocult21 Compendium: Urban Cultural Policy Profiles. (Eurocult21, Helsinki). Skot-Hansen, Dorte (2002) “Danish cultural policy: from monoculture towards cultural diversity”, International Journal of Cultural Policy 2, 197-210. 23 Statistics Finland (2006) Foreign-born population in Finland, Uudenmaa province and in Helsinki, 2004. Statistics subscribed 4.8.2006. Toikka, Mia (2001) Monikulttuurisuus ideologisena käytäntönä. Unpublished master thesis. (University of Helsinki, Helsinki). Wahlbeck, Östen (1999). Kurdish Diasporas. A Comparative Study of Kurdish Refugee Communities. (MacMillan Press LTD, London). Interviews Cortes-Tellez, Mikko, designer, Ministry of Education (an e-mail interview), 10.11.2006, Maula, Johanna, director, International Cultural Centre Caisa, 21.9.2006 Riila, Anu, coordinator of immigration affairs, City of Helsinki, 19.9.2006 Timonen, Pekka, director, City of Helsinki Cultural Office, 26.9.2006 Siikala, Ritva, director, Kassandra association, 17.10.2006 Authors Pasi Saukkonen Senior Researcher, D.Soc.Sci, docent Foundation for Cultural Policy Research (CUPORE) Tallberginkatu 1 C 137 00180 HELSINKI FINLAND Pasi.Saukkonen@cupore.fi Miikka Pyykkönen Senior Lecturer Dept. of Social Sciences and Philosophy PO Box 35 40014 University of Jyväskylä FINLAND miipyyk@yfi.jyu.fi 24