Table of Contents - Association of banks in lebanon

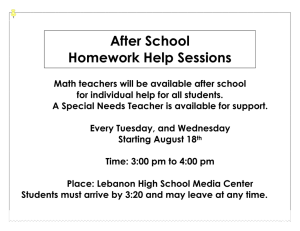

advertisement