Working Paper Diversity and Gender in the GIZ/AIZ

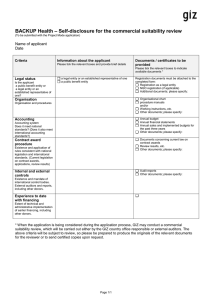

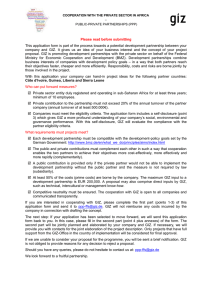

advertisement