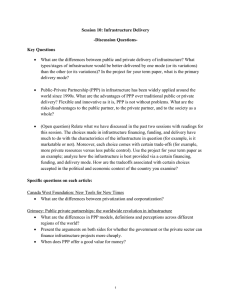

The Guide to Guidance - How to Prepare, Procure and Deliver PPP

advertisement