Future of Downtown San Jose

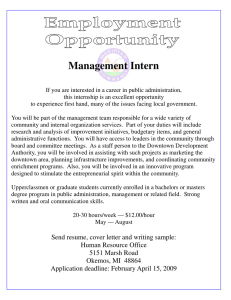

advertisement