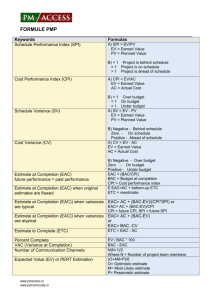

The Two Most Useful Earned Value Metrics: The CPI and the TCPI

advertisement

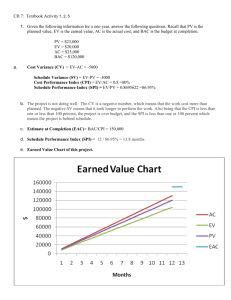

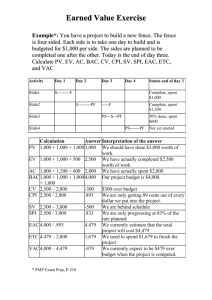

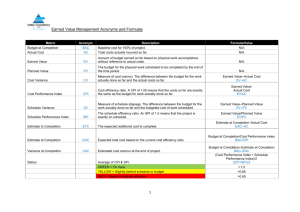

The Two Most Useful Earned Value Metrics: The CPI and the TCPI Quentin W. Fleming and Joel M. Koppelman Primavera Systems, Inc. W The Project Management Institute (PMI) has just released the 4th edition of their world standard on project management: A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge. Many new features have been added to this massive document, among them new coverage of an Earned Value metric called the To-Complete Performance Index. What is the ToComplete Performance Index and why is it important? This article describes its purpose and utility, and how it can work with the Cost Performance Index. henever a project commits to the employment of Earned Value to help manage their effort, users are suddenly inundated with a windfall of performance metrics which are available in no other project management technique. New acronyms suddenly emerge: PV, EV, AC, SV, SPI, CV, CPI, BAC, EAC, TCPI1, and on and on. While all of these performance indicators can have value to any project, the two Earned Value Management (EVM) metrics particularly critical to projects are the CPI and the TCPI. The CPI tells the user what has been accomplished for what has already been spent: Did the project stay within the budget, or was there an overrun? By contrast, the TCPI focuses on future work questions such as: What performance levels must be achieved on the remaining work in order to meet our financial commitment to management? While most practitioners of EV understand the utility of the CPI, most have rarely used the TCPI. It’s a pity because the TCPI, when used in conjunction with the CPI, provides a powerful set of tools in the management of a single project, a program, or a full portfolio of projects. EVM:The 10 Requirements As a general rule, whenever a project manager makes the decision to employ EV in the management of a project, that choice ideally should be supported by management, the stakeholders at all levels. Stakeholders must want to know the full truth. The reason? EVM performance data can be available to everyone working the project: the functions, senior management, the paying customers, and essentially all parties who have a vested interest in the success of the project. As long as everyone has a rudimentary understanding of what the EVM data means, everyone connected to the project knows what everyone else is doing. Thus, it is imperative that there 16 CROSSTALK The Journal of Defense Software Engineering be a management buy-in whenever a project manager elects to employ EVM on a project. The commitment to employing EVM requires both compliance with certain basic requirements and discipline on the part of everyone supporting the project. Based on our experience, we have listed the following 10 key requirements which must be met in order to successfully implement EVM. Some find these requirements overwhelming. See for yourself. These requirements are: “ ... the TCPI, when used in conjunction with the CPI, provides a powerful set of tools in the management of a single project, a program, or a full portfolio of projects.” 1. EVM requires that the project be fully understood, defined, and scoped to include 100 percent of the project effort. You need to know what constitutes 100 percent of the work in order to measure progress along the way. 2. EVM requires that the defined scope be decomposed. In other words, the scope is broken down into major management tasks that are selected as points of management control2, then planned and scheduled down to the detailed work package level. 3. EVM requires that an integrated and measurable project baseline be authorized, relating the scope of work directly to an achievable budget, then locked into a specific timeframe for performance measurement. It’s called bottom-up planning. 4. EVM requires that only authorized and budgeted work be accomplished. The effort being worked must be tightly controlled. Scope creep cannot be allowed. All changes must be managed, and not worked until specifically authorized by the project manager. 5. EVM requires that physical performance be measured (the EV) using previously defined schedule metrics. 6. EVM requires that the values earned be related to the PVs to reflect performance against the project baseline. EV less the PV represents a variance from the baseline plan. 7. EVM requires that the ACs being reported be consistent with the EV being measured to allow for an accurate portrayal of cost performance. The relationship of values earned to ACs reflects the true cost performance. EV less ACs provides cost performance. 8. EVM requires that forecasts be made periodically (weekly, monthly) as to how much time and money it will take to complete 100 percent of the project. 9. EVM requires that a full disclosure of actual results be made to all persons who have a vested interest in the project. All stakeholders will receive the same actual performance results. Only one set of books is allowed. 10. EVM requires that project management, in conjunction with management at all levels and customer stakeholders, decide on the appropriate actions to be taken to stay within the authorized project expectations. These 10 requirements are needed to successfully implement EV on any project. In our opinion, these requirements December 2008 The Two Most Useful Earned Value Metrics:The CPI and the TCPI constitute nothing more than following fundamental project management best practices. We will now discuss what we believe to be the most important EV indicators: the CPI reflecting completed performance, and the TCPI with a focus on the required future performance. What Is a CPI, and How Is it Used? The EVM CPI is a reflection of project cost efficiency. The CPI relates the physical work accomplished, expressed in its budgeted value, against the ACs incurred to accomplish the performed work. Budgets can be set with various monetary values, hours, deliverables, or anything else that can be measured. The issue: Is the project staying on target, underrunning, or perhaps overrunning costs? This concept is portrayed in Figure 1. Perfect cost performance would be defined as achieving a CPI of 1.0: For every dollar spent, we would get an EV equal to one dollar. Sometimes we do better, sometimes worse. This is a particularly critical metric to track because performance at less than 1.0 is a reflection of excessive costs spent against budget. Initial overruns are typically non-recoverable. Think about it: In order to recover an overrun, future work must be underrun. Rarely does this happen. The same conditions which may have caused the overrun in the first place are likely to occur again and again. Sometimes the CPI will reflect values over 1.0, suggesting that an underrun of costs is occurring. Care must be taken when actuals reflect an underrun of costs to budget. Oftentimes, this condition is simply the result of costs which are lagging (slow to be recorded in the organizational cost ledger). For example, let’s say you measure the EV and give full credit, but the related costs are not reflected in the cost ledger. The reason? Most of the project work may be performed by outside purchased labor (people who are not part of the internal labor system). Thus, there can be a time mismatch between the EV measured and the actual payment of the purchased labor invoices. The payment of invoices generally takes more time than the recording of labor. Underruns of costs are rare. And, if artificially caused by lagging ACs, the positive results can hide or offset problems that need management attention. It takes organizational discipline to make December 2008 Figure 1: Monitoring Earned Value Cost Performance sure that EV credits match the ACs. Why is the CPI so important? Because past performance can be used to accurately determine requirements for final performance, in order to meet financial goals. The cumulative (from the beginning) CPI has been shown to stabilize from about the 20 percent completion point of project performance. Empirical scientific studies by the DoD on 155 actual contracts has shown that at the 20 percent point of project completion, the final projected results will only change by plus or minus 10 percent [1]. What a finding! What useful data. In practical terms, one can immediately take the total authorized budget (BAC), divide it by the cumulative CPI, and predict the total costs of a project with an accuracy of plus or minus 10 percent. If management doesn’t like the final cost projection, then corrective action can be taken to change the forecasted results. Few project management techniques give a comparable earlywarning signal. This formula, the BAC/Cumulative CPI = EAC, can be used on the total project, or any subproject, or with integrated project teams to predict final results on their work. The CPI metric can be used to track periodic results (monthly, weekly, daily) or the cumulative position to see the long-term performance trends. What Is a TCPI, and How Is it Used? Whereas the CPI is an indicator of past cost performance, the TCPI has its Figure 2: The Relationship of Cumulative CPI vs. TCPI www.stsc.hill.af.mil 17 Data and Data Management TCPI using Management’s “Budget at Completion” (BAC): Work Remaining (BAC - EV) Funds Remaining (BAC - AC) = TCPI (BAC) sent a project with data not available with any other management tool. And while each metric can be useful, we believe that the two metrics described are particularly useful in the management of any project, or program, or a portfolio of projects. Reference 1. Christensen, David S. “Using Performance Indices to Evaluate the Estimate at Completion.” The Journal of Cost Analysis. Spring 1994: 19. TCPI using the Project Manager’s “Estimate at Completion” (EAC) Work Remaining (BAC - EV) Funds Remaining (EAC - AC) Figure 3: Two TCPI Formulas focus on future performance. At issue: What will it take to meet the goals set by management? The TCPI works in conjunction with the CPI, and is conceptually illustrated in Figure 2 (see previous page). The CPI can be thought of as sunkcosts; whatever the results, they cannot be altered. In the illustration shown, the cumulative CPI is at .75; for every dollar spent, only 75 cents of project work was earned. If the project is exactly 50 percent complete, one would need to accomplish $1.25 for every future dollar in order to stay within management’s budget. Will this happen? At best, it is highly unlikely. Opportunities for improvements are illustrated by the use of the TCPI. The formula for the TCPI is: The [Work Remaining] (defined as total Budget less the EV) divided by the [Funds Remaining]. Note that in Figure 3 there are two scenarios for Funds Remaining3. Funds remaining will focus initially on the authorized budget. Management will track performance against what it has authorized in the form of an official budget. However, once it becomes obvious that the budget is no longer achievable, management must determine how much money it will cost to complete this job (called the EAC). The project then stops work and makes a new forecast of what is needed to finish the job. Preparing a new EAC forecast can get emotional. Unrealistic optimism sometimes takes over, at the expense of realism. It is not uncommon for projects, when making a new EAC forecast, to assume that everything will suddenly go right, and that all project risks are behind 18 CROSSTALK The Journal of Defense Software Engineering = TCPI (EAC) them. Thus, an initial EAC may be unrealistic or unachievable. Piecemeal EACs are often the norm, where the EAC projection goes up each: month as actual performance is known. Using Figure 2 as an example, would an EAC requiring a future TCPI of 1.25 or 1.10 be achievable? Probably not. More likely, a TCPI of 1.0 or .90 would be reasonable. But it is painful to admit the full value of an EAC, having just acknowledged that the BAC is no longer valid. Conclusion Employing the EVM technique can pre- Notes 1. The terms are: Planned Value, Earned Value, Actual Cost, Schedule Variance, Schedule Performance Index, Cost Variance, Cost Performance Index, Budget at Completion, Estimate at Completion, and ToComplete Performance Index. All terms used in this article are consistent with the “Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge,” 4th edition, published in December 2008 by the PMI. 2. The points of management control are sometimes called project teams, subprojects, or control account plans, depending on the organization. 3. Figures used in this article are inspired by “Earned Value Project Management,” 3rd edition, Quentin W. Fleming and Joel M. Koppelman, PMI, 2005. About the Authors Quentin W. Fleming is a management consultant specializing in EV. He has been a consultant to the staff at Primavera Systems, Inc. since 1993. Fleming was on the core team that updated the PMI’s “Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge,” released in December 2008. He coauthored the book “Earned Value Project Management,” published by the PMI, with the latest edition released in 2005. Joel M. Koppelman is the co-founder and CEO of Primavera Systems, Inc. He co-authored the book “Earned Value Project Management,” published by the PMI, with the latest edition released in 2005. Primavera Systems, Inc. Three Bala Plaza West Bala Cynwyd, PA 19004 Phone: (610) 667-8600 14001 Howland WY Tustin, CA 92780 Phone: (714) 731-0304 Fax: (714) 731-0304 E-mail: quentinf@quentinf.com December 2008