Preparation of Coated Microtools for Electrochemical Machining

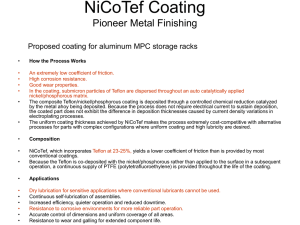

advertisement