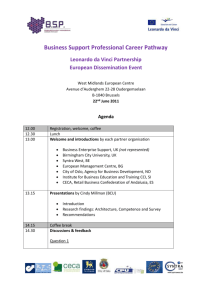

Dissemination strategies for Leonardo da Vinci pilot projects

advertisement