ARTICLE IN PRESS

Energy Policy 35 (2007) 6266–6280

www.elsevier.com/locate/enpol

Emerging in between: The multi-level governance of renewable energy in

the English regions

Adrian Smith

SPRU (Science & Technology Policy Research), University of Sussex, UK

Received 27 April 2007; accepted 19 July 2007

Available online 11 September 2007

Abstract

Analysis explains the emergence of a regional dimension to the multi-level governance of renewable energy in England. The case sits in

a tense, yet informative, position between the two poles of ‘ordered’ and ‘messy’ multi-level governance. These tensions, which are

currently debilitating, could be rendered more creative and fruitful if greater authority was devolved to the regions, and if policy learning

between the regions and the central government was institutionalised more deeply. Improved legitimacy and accountability mechanisms

must accompany increased authority. However, English ambivalence over regionalisation generally means such changes are unlikely.

r 2007 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Multi-level governance; Renewable energy; English regions

1. Introduction: regionalism and multi-level governance

Over the last 5 years, new networks of actors and

strategies have developed at the regional level in England,

whose aim is to advance renewable energy.1 Historically,

UK energy policy has been highly centralised. Whether

under state ownership or the post-privatised energy landscape, key policy decisions over energy markets, technologies, infrastructure and skills were taken within policy

networks operating at the central government level. This

picture appears to be changing. While the centre continues

to retain considerable powers over energy policy, there has

been some devolution to the English regions, particularly

in the area of renewable energy, accompanied by renewed

interest in sustainable energy among pioneering local

authorities. At each level—national, regional and local—

networks of business and non-governmental actors are

developing sustainable energy strategies and initiatives in

Tel.: +44 1273 877065.

E-mail address: a.g.smith@sussex.ac.uk

There has also been devolution of energy policy powers to the Scottish

Parliament and the Welsh National Assembly, but the focus of this paper

is England only.

1

0301-4215/$ - see front matter r 2007 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2007.07.023

partnership with policy-makers at those levels. Often,

actors and initiatives work across levels. In other words,

UK energy policy appears to be moving towards a ‘multilevel governance’ situation. By focusing on the recent

emergence of regional activities to promote renewables in

their multi-level context, this paper explores the issues

arising from this new situation.

In undertaking this analysis, the paper draws upon the

multi-level governance literature that developed in policy

studies over the course of the 1990s (Bache and Flinders,

2004a). That literature recognised and sought to reflect the

growing complexity of policy-making in modern states. It

was sparked by students of the European Union and their

interest in the increasing role and influence of sub-national

(regional) actors in European policy. Networks of governmental, business and civil society actors were identified

interacting across regional, national and European levels.

Gary Marks (1992) was one of the first to articulate this

‘multi-level governance’ concept, and to try and capture

the networked and multi-level nature of European policymaking. Given renewed attempts to reinvigorate European

energy policy, and the way this will interact with many

national and regional energy policies, one can anticipate

interest in multi-level governance increasing among energy

policy analysts.

ARTICLE IN PRESS

A. Smith / Energy Policy 35 (2007) 6266–6280

Since its inception in European studies, the multi-level

governance concept has come to be applied in a variety of

policy domains (e.g. environment, economy), and applied

at a variety of empirical levels (Bache and Flinders, 2004a).

This has included analyses of the changing face of British

politics (Gamble, 2000; Hay, 2002; Bache and Flinders,

2004b). Multi-level governance is concerned with the way

policy has moved from centralised governmental forms and

become distributed across levels and actors. The emergence

of a regional tier in renewable energy policy appears to fit

this pattern in England.

Of course, there has always been sub-national government. What interests students of multi-level governance is

the changing relations between these levels, and the

increasing variety of organisations and individuals beyond

the government who are becoming involved in policy. Part

of the perceived shift, argue analysts, is the way formally

nested and clearly demarcated hierarchies between levels

are giving way to more fluid, problem-focused networks

based at one level, but seeking to draw in help from other

levels. At the regional level, this can mean the clear lines of

command and separation of jurisdictions between national

and regional tiers are becoming blurred, as regional policy

networks seek to exert greater autonomy over their own

development in a globalising world, rather than being subaltern, sub-national administrative tiers transmitting policy

and economic development priorities set from above

(Storper, 1997; MacLeod, 2001; Herrschel, 2007).

However, formal regional governmental structures and

responsibilities remain. An accommodation has to be

reached between more dynamic and problem-focused

initiatives that seek to address regional challenges directly,

and constraints represented by the limited formal powers

available in regional structures. As an illustration, and as

we shall see later, regional policy bodies in England are

formally responsible for strategic planning and economic

development, but within clear (and limiting) frameworks

set by the central government. These constitute traditional,

hierarchical regional governance arrangements. Operating

within these regional institutional mandates, but also

trying to reach beyond them, are newer initiatives, such

as those to develop regional renewable energy centres, and

support for regional renewable energy businesses. The

argument in this paper is that there is a tension between the

formal, administrative arrangements and the networked,

problem-focused arrangements hampering renewable energy governance in the English regions.

This tension is identified in contrasting views in the

multi-level governance literature. One view seeks multilevel governance that is well ordered, has distinct functional separations across levels and distributes clear lines of

responsibility. The role of regional governance therein is

relatively fixed, territorialised and institutionalised. The

alternative view sees a more networked, fluid and messier

role for the regions within an overall governance system

that is similarly responsive across levels (Marks and

Hooghe, 2004). Roles, mechanisms and accountabilities

6267

are less clearly pre-defined. Regional roles are more

ambiguous. While the ordered view might attend to

steering and accountability in regional policy, the messier

view promotes dynamism and diversity. Fluid geometries

and functionalities permit experimentation in (regional)

governance, adaptations to different and dynamic contexts,

and nurtures policy learning.

In this paper, the implications of these issues are

explored for the emergence of the new regional level of

governance for renewable energy in England. Regional

agencies distribute significant public resources. Public

regional bodies invest over £2.2 billion each year in

regeneration activities and oversee a further £9 billion of

public spending. The energy demands of associated

activities pose significant implications for sustainable

energy use, of which renewable energy forms a part. Over

the last 6 years, the nine English regions have created a

variety of networks and policies to promote renewable

energy. Regional renewable energy governance draws upon

these broader regional commitments, while emerging

between more established renewable governance at national and local levels.

Significantly, the emergence of regional renewable

energy governance—coupled with political ambivalence

around English regionalisation—means the case sits in a

tense, yet informative, position between the two poles of

the ‘ordered’ and ‘messy’, formal and networked governance. Marks and Hooghe (2004) have tried to formalise

these contrasting tendencies into two ideal types for multilevel governance. Type I multi-level governance consists of

well-ordered, nested responsibilities, distributed neatly

between multi-functional institutions and networks, and

at a limited number of clearly demarcated levels. Type II

multi-level governance is more fluid and task specific, with

memberships intersecting across levels through more

flexible institutional designs. Regionalism under Type I

multi-level governance tends to the older certainties, with

regionalism within a hierarchical tier. Regionalism under

Type II multi-level governance exhibits newer, polycentric

characteristics, where interdependencies are negotiated

across levels (Bulkeley and Betsill, 2005). Each type carries

distinct advantages and disadvantages and is summarised

in Table 1.

The case study exhibits the characteristics of both ideal

types in dynamic tension, and analysis draws upon Type I

and II concepts to explain developments in regional

governance for renewable energy. On the one hand,

predominantly through the authority of regional strategies,

there has been an attempt to institute regional renewable

energy governance within a Type I multi-level governance

model. Multi-level governance in this view refines and

transmits national renewable energy policy goals down to

localities. On the other hand, through economic development, regional renewable energy can also be characterised

as Type II. Here regional policy networks experiment with

ways to draw renewable energy business into the region,

but with capabilities attenuated by an absence of formal

ARTICLE IN PRESS

A. Smith / Energy Policy 35 (2007) 6266–6280

6268

Table 1

Types I and II multi-level governance arrangements

Type I

Type II

Well-ordered, nested

responsibilities distributed across

multi-functional agencies.

Clear demarcations and lines of

accountability.

Fluid, sector specific networks

with memberships intersecting

across levels.

Accountabilities less clear, but

dynamism permits problem-led

experimentation.

Analogous to networked

regionalism: problem-focused

governance for region.

Regional activities to promote

renewable energy business and

innovation that draw upon formal

hierarchies and resources but

operate through networks.

Analogous to ordered regionalism:

clearly defined territorial tier.

Late 1990s in England

strengthening of formal regional

tier-economic and spatial issues—

adopts renewable energy targets.

authority at this level. Attempts by the regions to

contribute to multi-level governance are further undermined by the central government’s unwillingness to

empower and learn from adaptive experimentation.

Analysis is organised as follows. Section 2 introduces

renewable energy as a governance challenge with multilevel dimensions. Section 3 reveals the underlying tensions

arising from pursuit of problem-focused governance (Type

II) within a context of more general, territorially defined

regional governance arrangements (Type I). Section 4

illustrates the issues in more detail with an account of

practical governance activities promoting renewable energy

at the regional level. Section 5 considers how tensions,

which are currently debilitating, could be rendered more

creative and fruitful (through more attention to learning

and accountability). The paper draws upon empirical

material from primary and secondary documentation at

national, regional and local levels (e.g. strategy documents,

business plans, consultation responses to draft regional

economic strategies); 34 field interviews conducted between

February and July 2006 (see Appendix A); and participant

observation at regional events (e.g. Examinations in Public

of Regional Spatial Strategies, regional renewable energy

conferences, national-level meetings of regional energy

leads). Research focused on activities in all nine English

regions.

2. Renewable energy as a problem-focused governance issue

Policy objectives for transforming existing energy

systems into ones with greater renewable energy content

require co-ordinated efforts and changes among many

different actors, institutions and artefacts (Unruh, 2002;

Elzen et al., 2004; Smith et al., 2005). Renewable energy

systems are complex. It is consequently difficult to direct

them into being exclusively through hierarchical government measures like planning. Nor are they likely to arise

spontaneously through energy markets. Additional problem-solving activities must be coordinated and steered

outside government hierarchies and beyond markets

(Kooiman, 2003; Rhodes, 1997; Jessop, 1998; Pierre and

Peters, 2000). Such a problem-focused governance perspective in both policy analysis and practice does not signal

the demise of institutions of the state, nor of markets

(Scharpf, 1997), but rather a blurring between two longestablished (and ideologically potent) category distinctions

(Rhodes, 1997).

Considered in this way, renewable energy is a Type II

multi-level governance challenge. The central government

drew similar conclusions in its 2003 Energy White Paper. A

section titled Delivery through Partnership explains:

We will need to work with others to achieve these goals.

The products and services needed in future will depend

on business enterprise and innovation. Local authorities

and regional bodies are pivotal in delivering change in

their communities. We will continue to work closely

with the Devolved Administrations. We will continue to

need a sound basis of academic research and information. Independent organisations and voluntary bodies

can communicate messages to the public and help them

to get involved in decision-making. And Government

itself must change so energy policy is looked at as a

whole. (DTI, 2003, p. 112)

These private, public and civil society ‘partners’ must

negotiate (across territorial levels) the necessary processes

of innovation, business development, community involvement, knowledge production, infrastructure provision,

communication, regulation, market creation and policy

for sustainable energy systems.

There are various renewable energy systems, usually

based on core technologies (e.g. wind, solar, biomass,

marine, etc.), each of which can be configured in different

ways, and each of which is already developed to varying

degrees. They involve a mix of established energy utilities

and new sustainable energy businesses. Renewable energy

markets depend on public regulation and subsidy. Some

renewable energy systems match conventional consumption patterns, while others are predicated upon new user

behaviours. Finally, renewable energy projects make

unfamiliar demands upon existing institutions in planning

control, skills provision, infrastructure investment and

control systems.

Renewable energy governance must negotiate multiple

purposes into shared understandings, around which

activities can coordinate. This requires translation processes between different discourses in order to attain a

common framing of the problem or task at hand (Hajer

and Wagenaar, 2003; Smith and Stirling, 2006). A key task

for governance at the regional level has been to persuade

others that renewable energy is a vital component in the

development of their region.

Possessing key resources helps one wield influence in

governance, but only to the extent that other resourced

actors are persuaded or compelled to continue their engagement accordingly. Yet, because resource interdependencies

ARTICLE IN PRESS

A. Smith / Energy Policy 35 (2007) 6266–6280

Defra

ODPM

• Renewables Obligation

• Network & market regulation

• Other support programmes (LCB, R&D)

• Planning guidance (PPS22)

• Large investments (e.g. infrastructure)

Energy industry

Ofgem

DTI

National stakeholders

Central government (n = 1)

Regional Energy Network (SEPN)

Government Office

EST / CT / Envirolink

RDA Energy Leads

• Regional targets & strategies

• Regional Spatial Strategy, Housing Strategy

• RES: facilitate clusters and supply chains

• Regional R& D centres and energy agencies

• Partnerships and networks

Regional Assembly

RDA

DNOs?

Regional stakeholders

Regional government (n = 9)

Small renewable

energy businesses

Local authorities

EACs

Local stakeholders

6269

Local government (n = 354)

• Land use planning

• Local development frameworks

• Energy advice centres

• Supporting local initiatives

Fig. 1. The multi-level governance of renewable energy.

need not be symmetrical, indeed often are not, the basis for

negotiations takes place under power relations (Rhodes,

1997; Wilks and Wright, 1987). The need to enrol key

interests and material priorities will structure renewable

energy governance. These negotiations do not take place in

virgin terrain. Each region has its own geography, resource

endowments and socio-economy that structures the renewable energy options available, and lends greater or lesser

credibility to certain arguments about the best ways

forward.

Thus, a Type II, problem-focused approach identifies

three constituent governance processes. These are: establishing renewable energy discourses; building resourceful

actor networks; and negotiating commitment between

different interests (Keeley and Scoones, 2003). These

challenges are interrelated, in the sense that (policy)

network maintenance is built on negotiated problem

framings, which are influenced by discourses that reflect

and inform actors’ perceptions of their interests, which are

met through exchanges in networks, and so on. As such,

soft measures in governance—sharing views, building

networks, etc.—attain a significance that underpins harder

measures—implementing targets, making investments,

reforming institutions and infrastructures.

In practice, these processes are distributed across

territorial levels. The deployment of renewable energy in

a region is facilitated by governance arrangements interacting at the national, regional and local levels. Type I

multi-level governance considers the regional contribution

as deriving from its formal, general purpose capabilities in

developing spatial and economic strategies favourable to

renewable energy. Regional governance meshes with

complementary capabilities at higher and lower territorial

levels. The Type II perspective considers the regions

confronting the above challenges more entrepreneurially,

and working across levels to ensure renewable energy

industries flourish in their region.

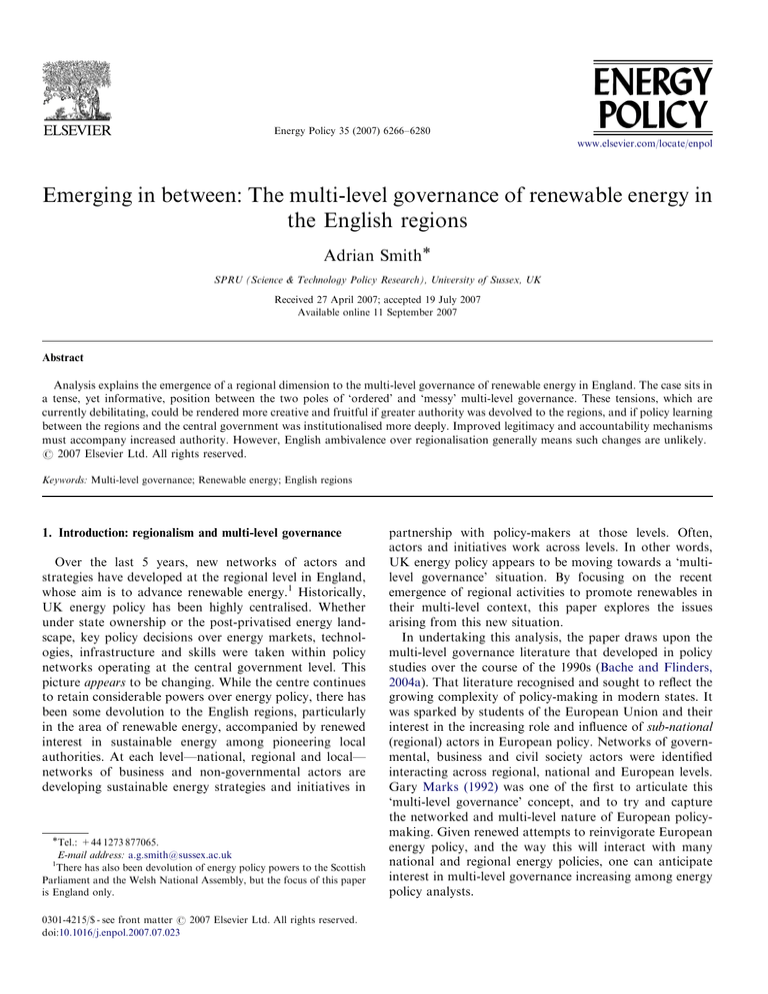

Fig. 1 summarises the actual distribution of governance

capabilities across the national, regional and local levels in

England. Broadly speaking, the national level is responsible

for market creation and support (e.g. the Renewables

Obligation), infrastructure provision, promoting technology development, and setting broad guidelines for land use

planning and renewable energy. Networks at this level are

inhabited by the Department of Trade and Industry2 (DTI,

responsible for energy policy), the energy market regulator

(Ofgem), the large energy utilities, the environment

ministry (Defra), and the planning and local government

ministry (formerly the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister,

ODPM, now the Department for Communities and Local

Government, DCLG).

The local level is where individual projects are implemented and take root. Local planning authorities operate

under national and regional guidance. Local energy advice

centres (EAC) support local stakeholders wishing to

participate in smaller-scale projects. Energy businesses,

large and small, are involved to the extent that they need

formal and informal local consent for their developments

(e.g. planning permits). Regional experience with renewable energy is channelled into the centre, and vice versa,

through a Regional Energy Network and meetings among

energy leaders in the regional development agencies

(below).

2

At the time of revising this paper (July 2007), some central government

departments had been re-organised, including the DTI. The DTI was

divided into a new Department for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory

Reform and the Department for Innovation, Universities and Skills.

Energy policy now resides in the DBERR, as does regional economic

development.

ARTICLE IN PRESS

6270

A. Smith / Energy Policy 35 (2007) 6266–6280

The regional level is discussed in the next two sections. It

consists of key regional bodies, some national energy

agencies with regional operations (such as the Energy

Savings Trust and Carbon Trust) and a few regional

stakeholders interested in renewable energy. Interestingly,

even though electricity networks in England have a

regional dimension, the (regional) distribution network

operating (DNOs) companies are poorly represented in

governance at this level, reflecting the fact that their core

business of energy markets and infrastructures is governed

primarily at the national level.

One advantage claimed for the regional level is an ability

to have knowledge about and work with people on the

ground, while retaining an ability to operate strategically.

Regional governance actors can share experience between

local councils who are pioneering, struggling or indifferent

towards renewable energy. They can feedback lessons to

the centre, while translating general policy goals into more

defined strategies closer to the ground. Similarly, companies and business opportunities can be identified regionally

in a way not available to local or central levels. Personal

contacts between people can be made and maintained

across a regional scale in a way impossible for civil servants

in London. Such capabilities open space for Type II

approaches within a more formal distribution of authority

(Type I). However, given the way policy levers for

renewable energy are distributed, with continued control

over market and infrastructure decisions at the national

level, it is in promoting softer measures where much

regional governance activity has focused.

The central government began encouraging regional

governance in renewable energy in 2000 in order to

contribute to both specific and general policy goals. These

goals were: specifically, the smoother operation of renewable energy policy as currently instituted at national and

local levels, and, generally, to contribute to the regionalisation agenda in government. A top-down view considers

regional institutions administering national energy policy

through their general competencies. An alternative view

identifies the regional level taking on a life of its own.

Rather than simply being a Type I conduit for policy, a

range of Type II regional initiatives seek to reframe energy

within regional contexts. Given an initial steer from the

central government, regional bodies have developed their

own renewable energy agendas that go beyond top-down

policy transmission. It is to these considerations of relative

hierarchy and autonomy, between Type I and II multi-level

governance, to which attention now turns.

3. Regionalism and Type I renewable energy governance

Regional governance for renewable energy emerged

through a specific problem focus (Type II) reinforced by

more general commitments to regionalisation (Type I).

This combination is discussed here, first, by focusing on the

specific problem of renewable energy governance, before,

second, considering it in the light of regionalisation

generally. Both these drivers derived from the centre. But

they subsequently opened space for a bottom-up initiative.

A tension becomes apparent between a dynamic, adaptable

and problem-driven regionalisation around renewable

energy, and a more ordered, territorially distinct and

general-purpose regional governance.

The specific, problem-focused driver behind regional

renewable energy governance was to accelerate the

deployment of renewable energy through the planning

process. A number of studies in the late 1990s identified

local and regional planning difficulties delaying renewable

energy projects, particularly wind farms, which are the

most commercially viable and largest contributor to

renewable energy goals (Mitchell, 2000; Hartnell, 2001).

Planning presented ‘a grave hindrance to achieving the

necessary growth of renewables’ (HOLSCEC, 1999, para.

215). The British Wind Energy Association produced data

suggesting regional inconsistencies in planning decisions

(BWEA, 2003). These criticisms arose at a time when a

stronger regional role in planning was being promoted by

the government and its advisors (RCEP, 2002).

The central government responded to these pressures by

giving the regional bodies a mandate and funds to conduct

regional renewable energy assessments, and to adopt

renewable energy targets in regional strategies (OXERA

and ARUP, 2002, p. 1). Energy Minister Helen Liddell

explained how the targets ‘will feed through to the

assessment of individual planning applications. It is

important that people see renewable energy schemes in

the national rather than the local context’ (DTI, 2000). The

ambition was for regional bodies to bring the planning

system into some synchronicity with national policy

ambitions for renewable energy (i.e. a 10 per cent target

for renewable electricity by 2010).

The more general driver was the regionalisation agenda

of New Labour, elected into power in 1997. Policy reviews

like the Energy White Paper presented opportunities to

embed regionalism in policy sectors. Moreover, the

planning ministry overseeing planning guidance was also

responsible for the regionalisation agenda. It was committed to improving conditions in declining regions of the

country, to recalibrate responses to international competition and to capture more effectively regional funds from

the EU (Tomaney, 2002; John and Whitehead, 1994;

Morgan, 2002). The leitmotiv for regionalisation in

England, as elsewhere, was to attract (globalising) capital

and raise the economic performance in each region,

principally through more coordinated regional investment

and infrastructure planning (Morgan, 2002). Regional

renewable energy governance has been refracted through

these injunctions.

Regional networks for promoting renewable energy

(Type II) have had to work through general-purpose

regional institutions (Type I). Regional Government

Offices (GO) were established in the nine English regions

in 1994. These were joined by Regional Development

Agencies (RDA) and Regional Assemblies (RA) in 1999.

ARTICLE IN PRESS

A. Smith / Energy Policy 35 (2007) 6266–6280

These bodies are responsible for key regional strategies and

form the focal core of regional governance networks. It is

the combination of these bodies, their mandates and the

strategies that constitute Type I regional governance

structures. They provide a territorially based, generalpurpose framework. Renewable energy became one (minor) issue among many within this framework.

The strategic responsibilities for each body are:

Government offices (GO): Oversee delivery of the

central government policy in the regions and feed

intelligence back to the centre. By 2004/2005 the GOs

were administering central government expenditure of

£9 billion and employed over 3000 civil servants. They

co-ordinate regional renewable energy partnerships.

Regional development agencies (RDA): Develop and

deliver regional economic strategies that boost competitiveness, growth, employment and skills. They invest

£2.2 billion each year into regeneration, and are the key

source of regional funding for renewable energy.

Regional assemblies (RA): Responsible for regional

spatial and housing strategies, and provide stakeholder

oversight of the regional economic strategy. Including

renewable energy provision in spatial and housing

strategies is a key regional policy lever for boosting

capacity.

Each body works in partnership, and with other

stakeholders, in developing the aforementioned strategies,

establishing networks, making investments and realising

initiatives. There is no clear hierarchy between economic

and spatial strategies: each is supposed to accord with the

other. Tellingly, both eclipse regional sustainable development strategies (SDC, 2005; Counsell and Haughton,

2003).

Type I hierarchies are apparent in these arrangements.

GOs are regional extensions of the central government.

The RAs provide a regional oversight of economic

strategising, and are responsible for spatial and housing

strategies, but strategies are signed off by the central

government. While RDAs have autonomy over how they

spend their budgets, it is the DTI that appoints their

business-led boards and establishes performance targets.

These targets, like the economic strategies, relate performance to conventional regeneration measures for employment, business creation, skills and regeneration

investments. RDA support for renewable energy has to

be justified against these criteria. In regions with established energy industries based in coal (Yorkshire and

Humber), nuclear power (North West) or gas (East),

renewable energy has to prove its regeneration credentials

against these more dominant sectors, and among other

sectors important for each region.

None of the regional bodies is monolithic in its relations

with other actors and policy domains. Each has its own

departments with their own mandates, priorities, subcultures and networks. Each looks outwards to different

6271

governance processes focused around policy domains and

issues of concern to those organisational sub-units

(Exworthy and Powell, 2004). Consequently, governance

actors in Type II renewable energy activities can be more

familiar with the policies and activities of renewable energy

specialists in other actor organisations, and at different

territorial levels, than they are with colleagues working in

the same organisation. Nevertheless, they are, ultimately,

constrained and have to work through the Type I regional

governance frameworks introduced here. Worked imaginatively, these provide certain latitudes for more flexible,

problem-focused approaches to renewable energy.

4. Type II multi-level governance and regional renewable

energy

The DTI provided each region with £100,000 in order to

facilitate renewable energy governance. Initially, this was

funding to conduct renewable resource assessments, facilitate partnership building and consultation processes, and

to establish regional targets. Since then, this annual grant

has helped develop regional renewable energy partnerships

and networks, and embed renewable targets into regional

strategies. The DTI grant is tiny in proportion to the task

of developing renewable energy systems, and small in

proportion to regional budgets generally. Nevertheless, the

funding seeded posts and launched dialogues. Apart from

some general direction, there were few strings attached,

meaning there was space to experiment.

Regional targets were developed through a pragmatic

blending of expert and public consultation on issues like

the technological and economic practicalities of utilising

available renewable resources (wind, sun, biomass, wave,

tidal); the proximity of large conurbations; the distribution

of existing energy infrastructures; planned housing expansion; beneficiary business already in the region; regeneration potential; and so forth. Table 2 reproduces the

diversity of target types across the regions.

Fig. 2 presents the actual performance in the regions in

terms of renewable resources used. Every region has

increased renewable electricity generation. Landfill gas is

a significant component for every region. Biomass is also

important, and has increased dramatically in some regions,

primarily due to co-firing in coal-power stations. Some

regions have increased wind energy, but only in some has

the rise been dramatic, and then mainly from low starting

positions. In all cases, there is still a long way to go.

Renewable energy targets are soft, in the sense that they

are long term, and carry no sanctions for non-compliance.

Some interviewees argued that it is not the target per se

that is important, but rather the processes involved in

target setting, and the dialogue and network building

associated with those processes. Building on this dialogue,

each region has created a sustainable energy strategy that

makes the case for renewable energy in it and suggests

stakeholder activities for fulfilling the targets. Energy

strategies forge regional discourse on renewable energy

ARTICLE IN PRESS

A. Smith / Energy Policy 35 (2007) 6266–6280

6272

Table 2

Regional renewable electricity targets and performance including landfill gas

Region

2010 Target

2005 Performance

Percentage of target met

East Midlands

East England

North East

North West

London

South East

South West

West Midlands

Yorkshire and Humber

410.5 MW; or 1780GWh

10% consumption

1500–2600 GWh

897–1478 MW

665 GWh

620 MW

11–15% generation

1250 GWh

674 MW

92.1 MW; 649.3 GWh

(1666.4 GWh res/26896 GWh cona) 100 ¼ 6.2%

479.3 GWh

265.3 MW

329.7 GWh

332.5 MW

(139.1 MW res/3125 MW genb) 100 ¼ 4.5%

1069.2 GWh

147.5 MW

22 (MW); 36 (GWh)

62

18–32

18–30

50

54

30–41

86

22

Source: DTI Energy Trends and regional documentation.

a

East of England regional electricity consumption for 2003 is 26,896 GWh (Source: DTI Energy Trends, December 2004).

b

South West regional electricity generating capacity at end of May 2006 is 3125 MW (Source: DTI, DUKES, 2006).

1800

Biomass

Landfill gas

Wind & Wave

Hydro

1600

1400

1200

GWh

1000

800

600

400

200

Ea

st

M

id

la

Ea

nd

st

s

M

20

id

03

la

Ea

nd

st

s

20

En

05

gl

Ea

an

st

d

20

En

03

gl

an

N

d

or

20

th

05

Ea

st

N

or

2

00

th

3

Ea

N

st

or

2

th

00

W

5

es

N

or

t2

th

00

W

3

es

t2

Lo

00

nd

5

on

20

Lo

03

nd

on

So

20

ut

h

05

Ea

So

st

20

ut

h

03

Ea

So

st

ut

2

h

00

W

5

es

So

t2

ut

0

h

W

03

W

es

es

tM

t2

id

00

W

la

5

es

n

Yo

t M ds

rk

2

id

00

sh

la

3

ire

nd

Yo

&

s

rk

20

H

sh

um

05

ire

be

&

r2

H

00

um

3

be

r2

00

5

0

Region & Year

Fig. 2. Renewable electricity generation in the English regions in 2003 and 2005. Source: DTI Energy Trends.

and urge actors to re-conceive their material interests in a

renewable energy future. Discussions through renewable

energy partnerships, their crystallisation in renewable

energy strategies and subsequent attempts to communicate

beyond the partnerships are part of this discursive element

of regional governance.

Subsequent activities are trying to modify influential

policy levers elsewhere, and draw in the resources needed to

put the strategies into practice. At best, regions facilitate

rather than act as a driving force. In this respect, regional

governance can be considered as one of trying to ensure

widespread ‘ownership’ of renewable energy strategies in

the region. Precisely because of this partnership approach,

however, the targets and strategies lack clear lines of

accountability.

At the core of renewable energy partnerships are ‘energy’

civil servants from the three regional bodies. In reaching a

common vision, partners have to negotiate their ‘different

organisational cultures, policy styles, finance structures and

modes of accountability’ (Exworthy and Powell, 2004,

p. 268). The partnerships have played an important role in

building broader networks of renewable energy advocates

in the region. Some partners were already active in trying

to promote renewable energy locally or regionally on their

own (e.g. leading local authorities, energy advice centres),

and they have benefited further from some of the funds,

ARTICLE IN PRESS

A. Smith / Energy Policy 35 (2007) 6266–6280

initiatives and strategising that regional renewable energy

governance has provided. Other partners have emerged as

a result of the regional governance initiative, for whom

renewable energy is a new concern.

An interviewee from one RDA said their regional

sustainable energy partnership was populated by ‘the usual

suspects’ that included energy advice centres, some local

authority officers, representatives from each regional body,

but few industry people (Interview 14, 27/02/2006). Even

the distribution network operators (DNOs), whose business has an obvious regional dimension, were, apart from

two regions (Y&H, NW), absent from the partnerships.

Also striking is the relatively low presence of renewable

energy business interests. As with the energy utilities more

generally, this reflects the fact that the strategic regulation

of their infrastructures and markets (i.e. core business

concerns) are a matter negotiated at the national level. The

regions have very little direct control over the energy

infrastructures in their territory. At best, they can

contribute to favourable contexts, but they do not take

the key decisions that have long-term consequences.

Regional renewable energy partnerships consequently

struggle to exercise wider authority. While there is open

recognition of resource interdependencies, and partners

often enjoy equal status, few partnerships enjoy high-level

support and spread throughout constituent organisations:

ingredients which Hudson and Hardy (2002) identify as

essential for successful partnerships. Given the way

partnerships have to rely on mutual consent and voluntarism, an important challenge remains to take partnership

commitments back to the constituent organisations, and

out to non-renewable policy networks.

While these challenges are considerable, they are not

completely debilitating. Renewable energy capacity and

business in the regions is improving. One cannot attribute

this performance exclusively to regional governance. The

target setters (regional bodies) are heavily dependent on

renewable energy developers, whose market incentive

mechanisms and infrastructure regulations remain in the

hands of the central government (Section 2). Renewable

energy targets may be important for those in regional

renewable energy networks, but to outsiders, especially

policy-makers pressed by harder targets in other regional

networks, they appear to be of low priority, far off and

someone else’s issue.

A tactic for overcoming this has been to incorporate

targets into statutory regional frameworks, and thereby

give them ‘some teeth’. Embedding regional renewable

goals into overarching economic, spatial and housing

strategies has become an important, if time-consuming,

governance activity. It tries to bring some Type I authority

into Type II activities. Each regional strategy has its own

institutional logic. The planning strategy must follow the

consultative and professional procedures and criteria for

spatial plan developments, and that cascade down from the

national level towards the local. The economic strategy

aims to boost the employment, competitive and business

6273

position of the region as conceived by the RDA, and

renewable energy must make its case accordingly. As one

interviewee explained:

It’s a hard task to get these threads through all the

agendas that are necessary and all the plan formulations

that are necessary. We spent years locally putting those

threads together, to make sure that housing is interested

in renewable energy, or planning, transport issues and

things like that. (Interview 25, 3/3/2006)

Those leading the development of these strategies do not

have renewable energy as a central preoccupation. Energy

officers have to ensure that each draft maintains a

renewable energy commitment. Making the case again,

and again, through internal and public consultation

processes. Fortunately, regional renewable energy assessments, partnerships and strategies have furnished considerable information and evidence. They also generated

contacts and networks through which more specific studies

or surveys could be commissioned in order to press the case

for, say, integrating renewable energy in buildings in the

housing strategy. Negotiation and bargaining was framed

by overarching, national commitment to renewable electricity generation, and had to be argued as contributions to

that end. This worked to attenuate higher aspirations

among regional renewable energy advocates. Nevertheless,

some innovative measures, like targets for integrating

renewable energy in new developments, could be deemed

necessary in order to ensure sufficient growth in regional

capacity. And some national organisations used regional

strategy making as an arena to press for these requirements

ahead of central guidelines and put pressure on the centre

through regional precedent.

In principle, there is greater latitude with the economic

strategy than the planning process, since the RDAs have

considerable discretion within their general performance

requirements. A renewable energy-minded RDA could

emphasise it in its strategy. Once the economic strategy

includes a commitment to renewable energy, it then

provides a basis for renewable energy advocates arguing

for the inclusion of renewable energy in the regeneration

investments of RDAs, such as development of a business

park. While such opportunities for institutionalisation were

widely recognised, Table 3 reveals a very mixed (but still

developing) picture for actually incorporating sustainable

energy features, including renewable energy. Some regions

are struggling to get to grips even with those renewable

energy governance levers available to them.

Apart from paper strategising, the greatest governance

activity in the regions has been the promotion of renewable

energy business. Four RDAs have created dedicated

renewable energy agencies to act as regional champions

and hubs for this activity, while other RDAs have kept this

activity in house, or choose to operate through regional

partnerships. This industrial strategy consists of a number

of streams of work:

ARTICLE IN PRESS

A. Smith / Energy Policy 35 (2007) 6266–6280

6274

Table 3

Incorporation of sustainable energy features in key regional strategies

Target strategy

RSS RES RHS RENS

Overall carbon dioxide

Overall renewables

Domestic efficiency standard

Domestic efficiency improvement

Renewables in new developments

Energy efficiency in new developments

Fuel poverty

CHP and district heating

Clean transport

Microgeneration

Public sector energy efficiency improvement

Business energy efficiency improvement

6

9

5

4

8

4

1

3

0

2

1

0

5

2

1

1

0

1

0

0

1

0

0

0

1

1

7

6

0

3

3

0

0

0

0

0

7

6

3

1

3

2

3

3

1

0

1

1

Source: Thumin et al. (2007).

RES ¼ regional economic strategy; RHS ¼ regional housing strategy;

RSS ¼ regional spatial strategy; RENS ¼ regional energy strategy.

identifying, communicating and promoting the regional

business potential of renewable energy;

mapping renewable energy business clusters in the

region and offering them support services;

analysing renewable energy supply chains and trying to

win component business for existing regional firms

capable of entering and competing in these supply chain

markets;

creating renewable energy research and development

facilities, thereby attracting international renewable

energy capital;

assessing regional renewable energy skill needs and

trying to integrate these in programmes of training

providers;

providing tools and services that help renewable energy

developers and others, such as assisting in access to

national and European funding competitions.

All of the regions have tried to measure and map existing

renewable energy business in their region. Renewables

Northwest, for example, estimate that there are over 100

companies with renewable energy business in their region,

employing 520 people, and with a combined annual

turnover of £7 million.3 Similarly, Renewables East

estimate the turnover in renewable energy goods and

services in the region as between £50 million and £100

million, and employ between 600 and 800 people.4 The

South West renewable energy strategy (2003) begins by

describing the environmental sector overall as supporting

over 100,000 jobs in the region and contributing £1.6

billion to the economy. The SW RES suggests that

renewable energy could create 12,000 new jobs and

generate an extra £260 million for the region’s economy.

3

http://www.renewablesnorthwest.co.uk/intro/intro2.htm (accessed 7

November 2006).

4

http://www.renewableseast.org.uk/GeneralInfo/FactsAndFigures.aspx

(accessed 8 November 2006).

These figures are underscored by the promotion of

exemplary renewable energy businesses in the region, or

potential projects that are at the feasibility stage.

Much of this promotional work is about creating a

serious business discourse around renewable energy, and

thereby attracting interest to the region and associated

public and private investment, both from within the sector

and outside. These kinds of activities are done through

networking, publications, help desks and attendance at

targeted regional business fairs. Regional renewable energy

conferences, exhibitions and prizes are also organised, all

aimed at promoting business in the region.

RDAs fund feasibility studies that help them and other

investors decide which kinds of renewable business

development to back. Inevitably, a number of regions do

the same kind of study, but this apparent ‘duplication of

effort’ has an important rationale. So, for example, regions

along the East coast of England (SE, E, NE) have all

studied the likely economic benefits arising from offshore

wind installations. These installations are planned at a

number of points along the coast and offer benefits

including provision of on-shore transfer and support

facilities. Not all regions can become ports for turbine

construction and maintenance. But each needs to know

what is going on and make informed decisions about the

competitive position of its own sites for attracting

developer investment. There is a question of competition,

but also needing to know if this really is a likely investment

(cf. shipping turbines over from northern Europe).

Business cluster analysis and supply chain studies are

important here. This work tries to match potential business

with regional firms whose existing skills, products and

services can be readily adapted to renewable energy

component or services markets. Some regions have focused

on the potential for penetrating relatively mature renewable energy supply chains; others have opted for a focus on

emerging renewable energy markets, in the belief that the

scope for capturing business is more open; while others

have done work in both areas. In all cases, activities focus

on helping regional firms enter renewable supply chains,

and attracting inward investment from renewable firms. In

less mature markets, activity extends to helping regional

firms commercialise new renewable energy technologies.

What is significant in this activity is how it engages with

the international level. Regional delegations attend international trade fairs, visit the European headquarters

of renewable energy technology manufacturers, and so

forth with a view to attracting activity to their region.

Regional renewable energy industrial strategy exhibits a

diversity of judgements for dealing with limited resources,

limited levers and engaging with renewable technology

processes whose local, national and international innovation dynamics are perceived differently. These are judgements that are difficult to make nationally—which was an

underlying rationale for the regionalisation of economic

development generally, not just renewable energy industrial

strategy.

ARTICLE IN PRESS

A. Smith / Energy Policy 35 (2007) 6266–6280

The lesson from the above activities is that inward

investment needs to play to specific geographic and

economic strengths. In this respect, the regions are in

competition, but starting from different positions, which

can sometimes be complementary. So, for example, the

NW can play to its internationally important petrochemical refining strengths in arguing for co-locating biodiesel

facilities near established diesel-processing facilities. Mass

production here will facilitate the supply to markets in

other regions.

Of course, regions can affect their relative advantages

through investments in infrastructure and skills. Four

regions have committed to regional research and development centres, with the aim of them subsequently retaining

new businesses on the back of successful research and

demonstration work. Again, there are elements of direct

competition for international capital, but also signs of

potential complementarities, in the sense that together

these centres present a network of innovative research and

development activity.

Plans in the SW are informative here because they

illustrate how regional actors have had to lobby at the

national level in order to help them attract international

renewable energy capital. The SW is committed to R&D

facilities in the less mature marine renewable energy

technology market (cf. wind energy in the East). The SW

RDA contributed £2million to a £15 million project to

establish a ‘Wave Hub’ off the North Cornish coast.5

However, in doing this the regional renewable energy

champion, Regen SW, recognised that the region had few

policy levers to influence technology development further.

So, in addition to doing much of the feasibility analysis for

the Wave Hub, Regen SW organised a national conference

on the finance and policy issues surrounding marine

technologies. This led to DTI support for Wave Hub,

and, coupled with lobbying from Scotland (Winskell,

2006), a policy review process that culminated in the

Marine Demonstration Programme supporting technology

developers. Regional governance has had to reach across

levels in order to influence people with the key levers. The

SW and Scotland have helped influence the national

marine agenda, but by providing facilities that will capture

that activity. Regions can create bottom-up pressure to

push policy-thinking forward, and help build the business

case.

This instance suggests that Type II regionalisation

is possible, as a few national policy advocates begin to

use the regional stage to pursue new ideas. However,

scope for innovation is constrained by interpretations of

national goals, and evidence about the reasonableness of

incorporating regional renewable energy ambitions into

regional strategies. When moving outside regional renewable energy governance networks, and seeking to engage

in statutory planning processes and broader policy networks, a Type I picture of checks and interpretations

5

http://www.wavehub.co.uk/

6275

against the national picture becomes an important point

of passage. The debates that ensue can sometimes

feed pressure back to the centre and lead to revised

national guidelines, as happened with targets for integrating renewable energy in new buildings, or even marine

support policy, but this happens under restraints set by the

centre.

Regional connection with the centre appears relatively

weak for renewable energy. The DTI employ a single civil

servant to cover the regional sustainable energy brief. A

Regional Energy Group meets periodically at the DTI,

under the auspices of the latter’s Sustainable Energy Policy

Network, and feeds back experiences and exchanges views.

A group of RDA energy officers operates a similar forum

with the DTI regions officer. While there is good

communication among the individuals involved, interviewees expressed doubts about wider influence and the ability

to embed shared lessons and experience. Other units in the

DTI make very limited use of the Group or regions—

preferring their national-level policy networks with large

utilities and national organisations. At the same time, the

regions provide varied levels of representation to and from

the region (in terms of legitimacy and authority)—none are

peak associations. Nearly all interviewees considered the

Group limited as a mechanism for transmitting policy

learning. At the same time, interviewees working in the

central government were frustrated at the limited resources

regions were devoting voluntarily to coordinating and

steering renewable energy governance. The centre recognises that regional capacity constraints hinder coordination

abilities across localities, but they appear unable to secure

more resources for regional renewable energy governance

from the central government budgets, or require it from the

regional spending pot.

5. Discussion: hierarchy, autonomy and accountability

The initial impetus behind regional governance for

renewable energy was attempts by the central government

to better transmit national goals to the local level. This was

primarily through the planning process and relied on the

creation and incorporation of renewable energy targets

into regional spatial and economic strategies. This push

worked through Type I governance. However, it also

provided an occasion for more specific, Type II governance

innovation. Regional advocates of renewable energy

formed partnerships to coordinate additional activities.

These activities are trying to bend and stretch regional

institutions, and reaching out across different territorial

levels, in an attempt to boost renewable energy in their

region. Ultimately, however, these initiatives are constrained by the more formal distribution of authority

under Type I arrangements: not least the retention of

considerable policy levers in the hands of the central

government.

Hierarchy persists in regional renewable energy governance. This confirms a governance perspective that considers

ARTICLE IN PRESS

6276

A. Smith / Energy Policy 35 (2007) 6266–6280

that, rather than signifying the ‘hollowing out’ of the state,

English regionalism represents an exercise in overload

reduction by the centre. Jessop argues that the central

government maintains the dominant strategic line through

governing the rules of the game (Jessop, 1998). The central

authority is retained through the controlled transfer of

implementation to others (Rhodes, 1997; Bache and

Flinders, 2004a, b). Whitehall orchestrates the hollowingout and retains powers to intervene through budgetary

controls and performance criteria (Whitehead, 2003; Lee,

2000; Wilson, 2003). This resonates with the Type I

position. The role of regional governance within the

multi-level system is relatively fixed, and territorialised,

and institutionalised hierarchically.

Targets have become a general device for attempting

hierarchical control in the English context. Renewable

energy is not the only policy domain with targets. Often

there is no clear indication as to how to prioritise between

targets. Exworthy and Powell (2004) found that targeted

agencies respond by differentiating between: (a) hard and

soft targets (i.e. those with immediate operational consequences or not, such as the directness of relationship

between target performance and future budgets or individual career trajectories), (b) those that can be easily

measured and controlled, and (c) how targets relate to

short-term policy measures (cf. longer-term aspirations).

Yet the picture for renewable energy targets is not as

clear-cut as the literature suggests. Section 4 concluded by

suggesting that there was actually little appetite within the

central government to direct and steer renewable energy

governance through the English regions. Few mechanisms

were put in place beyond a nudge to make the planning

strategy friendlier towards renewable developments. Targets are weak according to the Exworthy and Powell

criteria; the budget available (£100,000 per annum) is tiny;

and there are few strings attached to this funding. Central

planning guidelines have subsequently tightened in favour

of renewable energy. The central government has kept the

strategic line, such as it is, simply by doing nothing to

empower the regions over renewable energy.

Nevertheless, the nudge from the centre did send out

wider ripples, and provided space for more autonomous

governance experimentation within each region. A stronger

Type II view concedes that the central government

provides an important framework, but governance activities are increasingly shared and contested by actors

operating across different territorial levels. Regional actors

can operate at a variety of levels simultaneously in seeking

their goals, being involved in pushing initiatives regionally,

while helping develop policies nationally or forging direct

links internationally (Rosenau, 2004). Governance arenas

and policy networks are interconnected rather than neatly

nested (Bulkeley and Betsill, 2005). Interdependencies can

enable some parts of lower-level activity to exercise a

degree of autonomy, and permit flexibility and diversity in

governance better matched to problems and ‘action

situations’ (Ostrom, 2005).

While renewable energy governance in the region might

have struggled to make its voice heard among broader

strategising, it was not entirely impotent. Key strategies do

incorporate commitments to renewable energy, and regional champions and centres seek to develop renewable

energy industries in their regions. However, just as the

central government’s indifference has provided space for

Type II initiative, so it starves that initiative of powers to

really drive developments. Rather, Type II activity in the

regions simply facilitates and smoothes processes of

renewable energy deployment driven by national policy.

Regional autonomy is weak. The director of Energy West

Midlands, a regional renewable energy champion, wrote in

March 2006:

To enable these regional and local initiatives to grow

will require a significant increase in resources and

funding commitment to support and grow this implementation route to the level necessary to achieve

delivery on the scale required [sic]. Without such a

commitment to invest in regional and local implementation then we will struggle to address the heart of the

problem which is an increasing demand for energy from

all sectors (Energy WM, Response to Energy Review,

23/03/06).

Depressing as this picture is, regional governance does

point to future possibilities. There is probably no escape

from the tension between Type I and Type II positions, and

we should expect them even in more empowered regional

governance for renewable energy. Such contradictory

forces drive governance developments (Rosenau, 2004).

Hesse argues:

Advocates of decentralized self-guidance and control

often fail to recognize that highly differentiated societies

and pluralistic, fragmented institutional systems create a

growing need for collective steering, planning and

[consenus] building (Hesse, 1991, p. 619; quoted in

Rhodes, 1997, p. 195).

Alongside the devolution of decision-making and extensions to participation emerge pressures to co-ordinate and

steer developments centrally (Pierre and Stoker, 2000).

Regional studies debate the degree to which ‘regions have

merely become useful conduits for the delivery of the

central government policies and targets or whether they

have emerged as venues for promoting a more holistic

approach to strategy making’ (Ayres and Pearce, 2005,

p. 584). We see that debate in renewable energy governance

in the English regions, albeit in very limited terms.

Renewable energy governance in the regions lacks authority in relation to the centre and more general Type I

regional institutions. But this has not been for want of

trying, and those efforts have spawned a variety of

governance activities around industrial strategy suggestive

of what might be possible with greater support and

authority.

ARTICLE IN PRESS

A. Smith / Energy Policy 35 (2007) 6266–6280

Stoker (2002, p. 418) provides a hopeful perspective on

this situation. He argues that English regionalisation was

‘in part deliberately designed to be a muddle in order to

both search for the right reform formula and create a

dynamic for change by creating instability but also space

for innovation’. In other words, incoherence in regional

governance arrangements can have a coherent rationale.

An ambiguous combination of Types I and II can be

considered both problematic and beneficial.

The central government may be deliberately vague about

how the regions should develop their governance for

renewable energy, because the centre has no strong views,

and wishes to see what works effectively. One feature

needed to turn the ‘muddle’ to advantageous effect is

processes for continually learning and reforming governance in the light of experience:

Experimentation will work at its best where the system

develops an extensive capacity to learn about what

works and a capacity to spread best practice. (Stoker,

2002, p. 433).

According to Stoker (2002, pp. 421–422), this potentially

beneficial dynamic is really open only to those with

‘substantial formal power’. In other words, while situations

of flux and uncertainty are experienced by subordinates,

only higher levels retain power to act upon consequential

outcomes. While a variety of regional renewable governance forms have been launched and encouraged—e.g.

bidding partnerships, multi-actor area strategies, and

awareness raising—the central government takes the lead

role in setting the agenda for this experimentation and

(not) deciding what to do with it. Learning from Type II

experimentation requires adaptive Type I arrangements.

Unfortunately, for renewable energy in the regions, it

seems these learning and experimental mechanisms are

poorly institutionalised. The Regional Energy Group is

acknowledged by participants to be of limited effect.

Regional renewable energy governance has relatively poor

standing within regional institutions and in central policy

networks. Neither the regional nor the central levels are

systematically monitoring, evaluating and adapting governance arrangements for renewable energy.

More vigorous regional governance for renewable

energy can be imagined. Industrial strategy points to what

could be possible with greater resources and authority

devolved to the regional level. The RDAs currently spend

less than one per cent of their discretionary budgets on

renewable energy.6 No GO devotes a full-time position to

sustainable energy governance, and only lower-level

officers are involved. With greater effort and authority,

more robust regional initiatives could be envisaged. More

say over regional infrastructure development and regional

energy markets would transform the leverage available to

renewable energy partnerships and centres of excellence.

6

Data and estimates available from the author.

6277

Were such a reinvigoration to occur, increased authority

would have to be accompanied by greater accountability

and legitimacy. Currently, renewable energy governance,

regionally and generally, is highly technocratic. Specialist

partnerships and policy networks dominate decisions. This

is a generic risk with Type II multi-level governance. As

problem-focused complexity and institutional hybridity

increases, lines of accountability become both more

baroque and less clear-cut. ‘Fragmentation erodes accountability because sheer institutional complexity obscures who

is accountable to whom and for what’ (Rhodes, 1997,

p. 101). While policy-making moves, conventional democratic oversight stays still (Olsson, 2005). Elected representatives are not central in regional discussions around

renewable energy. Accountability, where it exists, refers

indirectly to different territorial levels to those of the

regional renewable energy partnership. So, for example,

accountability rests in the fact that RDA Boards are

appointed by and accountable to elected central government Ministers rather than regional citizens (Wilson, 2003).

Inclusion based around representative democracy may not

be adequate, and will need complementing more directly

and imaginatively with new forms of legitimacy under

future Type II experimentation (Humphrey and Shaw,

2004; Bache and Flinders, 2004a).

English regionalism suffers a general lack of public

legitimacy. Regionalisation suffered a set-back when voters

in the North East rejected plans for a directly elected

regional assembly in November 2004.7 Deputy Prime

Minister John Prescott was a particular champion of

regionalisation, and the agenda has suffered under his

political decline. Alternative configurations have been

championed by the government, such as the city-regions

idea, or a new localism. Broader political commitment is

even less certain. The Conservatives repeatedly state an

intention to abolish RAs (but not RDAs) and return

powers to local and county-level government. The prospect

of more vigorous regional renewable energy governance is

slim.

A lack of explicit consideration for an English regional

role in the third annual report on progress under the 2003

Energy White Paper (when previous years had reported

regionally), nor mention of future regional roles in the 2006

Energy Review, underscores such a shift (DTI, 2006).

Following on from the review, and more recently, the

Energy White Paper 2007 includes a chapter on Devolved

Administrations, English Regions and Local Authorities,

and Annex A of the White Paper lists some regional

activities in a single paragraph of its fourth annual report

of progress against the 2003 White Paper. While the White

Paper restates the strategic potential of the RDAs in

promoting renewable energy, and presents some information on regional energy initiatives (DTI, 2007), none of this

7

The North East is considered to have the strongest regional identity in

England.

ARTICLE IN PRESS

6278

A. Smith / Energy Policy 35 (2007) 6266–6280

represents any advance on the 2003 White paper. There

appears no attempt to better connect regional learning with

central policy-making. Moreover, the political climate and

broader discourse on regionalisation generally remains

contested in English politics, which creates an uncertain

context for developing regional governance for renewable

energy. The lessons generated by many instructive, but

weakly influential, regional activities are likely to continue

to be unheeded.

6. Conclusions

This paper has sought to understand the development of

regional promotion of renewable energy in the English

regions through a multi-level governance analytical framework. The advantage of that analytical framework rests in

how it demonstrated firstly how the problem-focused,

networked governance activities among renewable energy

professionals in the regions was initially empowered, but

ultimately constrained by the formal administrative mandates of regional institutions; and, secondly, how regional

governance has to be understood in relation to nationallevel powers. Without such an analysis, one could be

distracted by the wealth of regional strategising and miss

the fact that hierarchy persists in the delivery of energy

policy.

Regional governance for renewable energy is in a weak

and uncertain position, despite the best intentions and

concerted efforts of those involved. The most significant

developments have been the negotiation of targets into

Type I regional strategies. Softer, Type II measures are

contributing to awareness of renewable energy in the

regions, such as statements of commitment in regional

economic strategies, the creation of networks and partnerships, and advice and support mechanisms around

industrial strategy. However, all this activity is framed

and justified within the economic regeneration priorities

of Type I regional arrangements. Throughout, the more

problem-focused Type II activities ultimately depend on

Type I authority for their effectiveness. This constrains

the space for experimentation. Significantly, it also

compounds the relative lack of priority renewable energy

has in the regions, because formal powers under Type I

regional arrangements do not extend to the regulation of

markets and infrastructures on which renewable energy

expansion is so dependent. At best, regional governance

augments with softer measures the relatively stronger

authority over renewable energy coming from the central

government.

Reliance on formal powers was most evident in the case

of target setting. At one level, in trying to give the regional

renewable energy targets more ‘teeth’, advocates had to

negotiate more general economic and planning strategy

procedures and standards. This negotiation reminds us that

all policies are filtered through layers of bureaucratic

routine, and that any initiative has to attend to these more

mundane, repetitive, yet important processes, in order to

ensure that goals attain official commitment. However, this

case also indicates that even once the targets get official

approval, they do not exist in isolation, and have to

compete against many other targets for the attention and

priorities of policy and administrative bodies. Regional

renewable energy governance has to be considered within

this broader context of target-driven governance.

The case also demonstrated how targets struggle to move

beyond paper exercises without the commitment of

significant resources. Obvious resources are finance,

organisational resources, skills and technologies, but

political will at central and regional policy levels proved

to be a vital, and missing, resource in this case. Regional

initiatives are struggling to connect and unlock such

resources on a large scale, and currently remain limited

to an impressive, but restricted, list of star projects. There

is a long way to go, for instance, before sustainable energy

becomes institutionalised in the routine, day-to-day general

practices of regional bodies and their regeneration activities. Those involved in Type II, problem-focused renewable energy advocacy lack sufficient formal Type I powers

to demand the resources necessary to realise their projects

and reach their targets. Instead, they can only move at the

pace of voluntary, partnership commitments at the

regional level, and opportunities created by more influential policy developments at the the central government

level.

Analysis finds the most successful soft measures under

Type II activities have realised regional discourses around

renewable energy, but that this has been relatively

technocratic and limited to the renewable energy community. Arguments for renewable energy are predominantly

framed and presented in terms of contributions to Type I

agendas for competitive regions. Regional resource mobilisation remains insufficient for the task, and significant