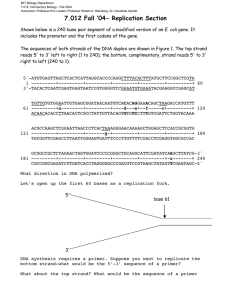

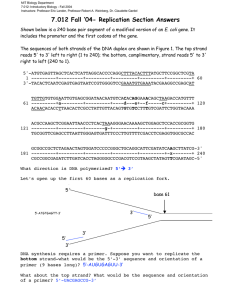

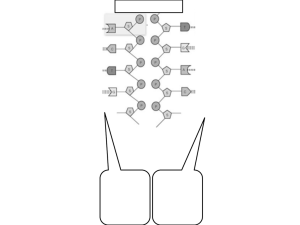

DNA2 drives processing and restart of reversed replication forks in

advertisement