Thailand Supporting Small-Scale Renewable Energy Producers

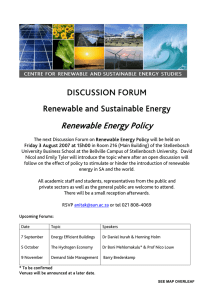

advertisement

Renewable Energy Supporting Small-Scale Renewable Energy Producers Thailand aims for rapid growth in renewable energy Small power producers play key role The expansion, diversification and greening of the national energy supply to help meet growing energy demand are key objectives of the Thai government’s Power 1 Development Plan 2010 to 2030. The Ministry of Energy projects that energy demand will increase nearly 40 percent over the next decade, reaching 100 million 2 tons of oil equivalent per year by 2021. The rapid growth in energy demand is leading to increased greenhouse gas emissions, with carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions 3 due to energy consumption totaling about 278 million metric tons in 2010. In addition to growth in greenhouse gas emissions, domestic energy security is a concern. In 2009, Thailand imported 60 percent of its total energy supply to meet its 4 demand. The government’s policy to promote development of domestic renewable energy resources evolved considerably over the past two decades. The new 10-Year Alternative Energy Development Plan (2012 to 2021) set an overall target to increase the share of renewable energy from about 9 percent of total energy consumption in 2011 to 25 percent in 2021. The plan is projected to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 76 million metric tons of CO2-equivalent per year by 2021 relative to a businessas-usual scenario. The target is considerably more ambitious than the 12 percent target for 2022 established in the previous 15-year Renewable Energy Development 5 Plan 2008 to 2022. A key component of the government’s strategy is the extension of a program to provide incentives and remove barriers to renewable generation by Small Power Producers (SPP) and Very Small Power Producers (VSPP). Small producers lead the charge The SPP and VSPP Programs evolved as part of the government’s efforts to promote diversification of electricity supply and rural electrification by independent power producers. The Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (EGAT) controls transmission and over half of electricity generation, and two public utilities manage distribution.6,7 The SPP Program was first launched to promote cogeneration (combined heat and power) and renewable generation under the 1992 Energy Conservation Promotion Act. The government required the Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand to purchase output from SPPs with a maximum installed capacity of 90 megawatts (MW). In 2001, the government augmented the SPP Program by introducing a five-year pilot “adder,” or feed-in premium, for renewable electricity generation funded through the government’s Energy Conservation 1 Promotion Fund. Small Power Producer cogeneration projects are not eligible for the 8 adder rates. In 2002, the government added a VSPP Program to support power producers with capacity up to 1 MW, particularly biogas producers from pig farms and food processing industries. The government offered very small producers simplified regulations and the ability to sell power directly to the distributing utilities and customers instead of EGAT. The government set rates in relation to the avoided cost of power, which is the marginal cost to EGAT of producing or purchasing power at 9 market rates. In 2006, the government expanded the definition of VSPP to include producers of 10 MW or less, and they added a technology-specific feed-in premium to ensure support for different types of renewable generation. Consistent with this 10 change, the government modified SPPs to include producers of 10 to 90 MW. Under the current policy settings supporting the new 2012 to 2021 energy plan, separate adder rates apply for renewable generation according to fuel type and capacity. Additionally, projects receive special bonuses if they have certain characteristics, such as replacing diesel and being located in specific provinces. The additional adder for projects in three southern provinces reflects relative investment risks in those provinces. The adder rates apply for seven to 10 years once commercial operation begins. In addition to the adder rates, long-term (five to 25 year) power purchase agreements with EGAT support Small Power Producers. EGAT carries the market risk in these agreements, while SPPs carry the operating and fuel price risks. SPPs do not have direct access to the state-owned distribution grid for general power distribution, but they can contract directly with nearby industrial customers using private distribution lines.11 Figure 1: Adder Rates for SPPs and VSPPs Using Renewable Energy (August 2012) Adder Rates (USD/kWh) Additional bonus for projects in 3 southernmost provinces (USD/kWh) Additional bonus for projects that offset diesel fuel (USD/kWh) Wind Installed capacity ≤ 50 kW Installed capacity > 50 kW 0.14 0.11 0.05 0.05 10 Solar PV 0.21 0.05 0.05 10 Biomass Installed capacity ≤ 1 MW Installed capacity > 1 MW 0.02 0.01 0.03 0.03 7 0.02 0.01 0.03 0.03 7 Mini and micro hydropower Installed capacity 50-200 kW Installed capacity < 50 kW 0.03 0.05 0.03 0.03 7 Waste Anaerobic digestion/landfill Thermal process 0.08 0.11 0.03 0.03 7 Energy Source Biogas Installed capacity ≤ 1 MW Installed capacity > 1 MW Sources: Olz, S. and M. Beerepoot; Osborne, Christopher. Subsidized period (years) 2 Small Power Producers and VSPPs benefit from other forms of financial support provided under the government’s Energy Conservation Promotion Fund. These include soft loans and investment subsidies for select types of renewable energy (e.g. biogas generated from livestock waste, municipal solid waste, and wastewater from tapioca starch, palm oil and ethanol factories, and electricity from micro-hydropower generators); technical assistance; and the ESCO Fund. Projects are also eligible for 12 crediting under the Clean Development Mechanism. Small Renewables Set To Grow As the government made modifications over time, the effectiveness of the SPP and VSPP programs increased. By December 2011, 67 renewable energy SPP projects were under some form of proposal, development or implementation, with a potential capacity of nearly 2.5 gigawatts (GW); and 1,890 VSPP projects were under proposal, 13 development or implementation, with a potential capacity of 6 GW. The SPP and VSPP programs have been effective in supporting diversification of energy sources and improving rural electrification goals of the government’s national plan. Looking forward, the revised Power Development Plan 2010 to 2030 assumes that SPPs and VSPPs will supply small but still significant renewable generation and cogeneration capacity. From 2012 to 2020, small and very small producers are projected to account for approximately 9.5 GW (with 5 GW from co-generation 14 and 4.5 GW from renewable energy) of growth in generating capacity. To put this growth in context, in 2011 Thailand’s total installed power generation capacity was approximately 32.4 GW. The government has announced plans for policy adjustments to support these targets, including transitioning from the adder for renewable generation to a fixed-price tariff system, preparing for development of a Smart Grid transmission system, amending laws and regulations which disadvantage renewable energy development, and promoting research and public education on 15 renewable energy generation. References Chotichanathawewong, Q. and N. Thongplew. 2012. “Development Trajectories, Emission Profile, and Policy Actions: Thailand.” Asian Development Bank Institute, Working Paper 352. Web. September 2012. <http://www.adbi.org/workingpaper/2012/04/12/5045.dev.trajectories.emission.thailand/> Department of Alternative Energy Development and Efficiency, Thailand Ministry of Energy. 2012. “The Renewable and Alternative Energy Development Plan for 25 Percent in 10 Years (AEDP 2012-2021).” Web. September 2012. <http://www.dede. go.th/dede/images/stories/dede_aedp_2012_2021.pdf > Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand. June 2012. “Summary of Thailand Power Development Plan 2012-2030.” Web. November 2012. < http://www.egat.co.th/en/images/ stories/pdf/PDP2010-Rev3-Eng.pdf> Olz, S. and M. Beerepoot. 2010. “Deploying Renewables in Southeast Asia: Trends and Potentials.” International Energy Agency Working Paper. Web. October 2012. <http://www.iea. org/publications/freepublications/publication/Renew_SEAsia. pdf> 3 Endnotes Note: All currency conversions from THB to USD were calculated using the exchange rate on August 4, 2012 (1 USD = 31.48 THB). 1 Department of Alternative Energy Development and Efficiency, Thailand Ministry of Energy. 2012. “The Renewable and Alternative Energy Development Plan for 25 Percent in 10 Years (AEDP 2012-2021).” Web. September 2012. <http://www.dede.go.th/dede/images/stories/dede_ aedp_2012_2021.pdf > 2 Ibid. 3 US Energy Information Administration. “International Energy Statistics.” Web. September 2012. <http://www.eia.gov/ cfapps/ipdbproject/iedindex3.cfm?tid=90&pid=44&aid=8> 4 International Energy Agency. 2011. “2009 Energy Balance for Thailand.” Web. October 2012. <http://www.iea.org/stats/ balancetable.asp?COUNTRY_CODE=TH> 5 Department of Alternative Energy Development and Efficiency, Thailand Ministry of Energy, 2012, op cit. 6 7 8 Olz, S. and M. Beerepoot. 2010. “Deploying Renewables in Southeast Asia: Trends and Potentials.” International Energy Agency Working Paper. Web. October 2012. <http://www. iea.org/publications/freepublications/publication/Renew_ SEAsia.pdf> Palang Thai. 2010. “Feed-in Tariffs and South-South Policy/ Technology Transfer: The Evolution and Implementation of Very Small Power Producer (VSPP/SPP) Regulations in Thailand and Tanzania.” Presentation at the Monterey Institute for International Studies, Monterey, California, USA, 8 May 2010. Web. October 2012. <http://www.palangthai.org/ en/vspp> Ruangrong, P. 2008. “Thailand’s Approach to Promoting Clean Energy in the Electricity Sector.” Paper presented at the Forum on Clean Energy, Good Governance and Regulation, Singapore. 16-18 March 2008. Web. September 2012. <http://electricitygovernance.wri.org/files/egi/Thailand. pdf> 750 First Street, NE, Suite 940 Washington, DC 20002 9 Palang Thai, 2010, op cit. 10 Ruangrong, P, 2010, op cit. 11 Olz, S. and M. Beerepoot, 2010, op cit. 12 Chotichanathawewong, Q. and N. Thongplew. 2012. “Development Trajectories, Emission Profile, and Policy Actions: Thailand.” Asian Development Bank Institute, Working Paper 352. Web. September 2012. <http://www. adbi.org/working-paper/2012/04/12/5045.dev.trajectories. emission.thailand/> 13 Wongkot Wongsapai, Assistant Professor, Faculty of Engineering, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Chiang Mai University, personal communication to Catherine Leining on 3 July 2012. 14 Wongkot Wongsapai, Assistant Professor, Faculty of Engineering, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Chiang Mai University, personal communication to Catherine Leining on 3 July 2012. 15 Department of Alternative Energy Development and Efficiency, Thailand Ministry of Energy, 2012, op cit. Figure Section Figure 1: Adder Rates for SPPs and VSPPs Using Renewable Energy (August 2012) Olz, S. and M. Beerepoot. 2010. “Deploying Renewables in Southeast Asia: Trends and Potentials.” International Energy Agency Working Paper. Web. October 2012. <http://www.iea. org/publications/freepublications/publication/Renew_SEAsia. pdf> Osborne, Christopher. “Thailand’s renewable energy adder rates.” AsianPower, August 8, 2012. Web. October 2012. < http://asian-power.com/power-utility/commentary/ thailand%E2%80%99s-renewable-energy-adder-rates> p +1.202.408.9260 www.ccap.org CCAP CENTER FOR CLEAN AIR POLICY