IN THE FAIR WORK COMMISSION Matter No.: AM2012/18 and

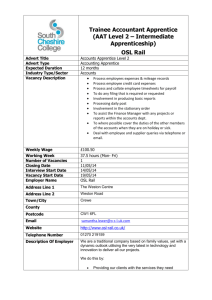

advertisement