ESL Students in California Public Higher Education

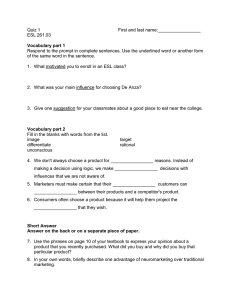

advertisement