Tacit Knowledge Capture and the Brain

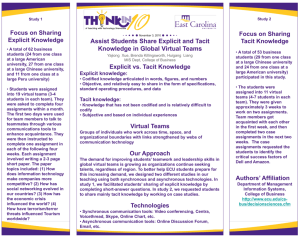

advertisement