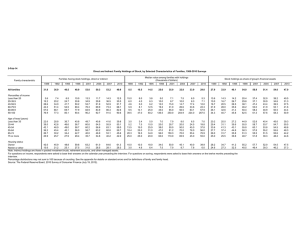

Red and Blue Investing

advertisement