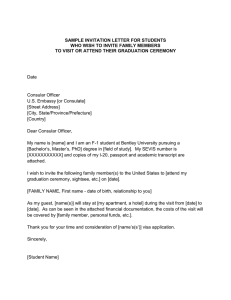

Extraterritorial Powers of the Consular Office

advertisement