Broken English

advertisement

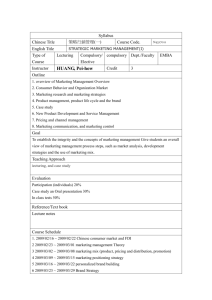

Spotlight on Asia Broken English With the growing importance of the Chinese market, DLA Piper’s Edward Chatterton and Ann Cheung offer guidance to brand owners doing business in China T he problem of trademark piracy is well-known in China and, because of China’s first-to-file trademark system, trademark piracy continues to be a thorn in the side of overseas (ie non-Chinese) brand owners. An additional and somewhat less well-known problem occurs where the overseas brand owner has registered its brand but has not registered a Chinese equivalent. Out of a total population of 1.4bn, only around 10m Chinese people speak English. This stark linguistic fact means that, notwithstanding the huge growth in the number of people learning English in China, even very famous overseas brand will be referred to by a Chinese language equivalent of the overseas brand. If the brand owner does not choose a Chinese language equivalent for its brand, the mere fact of using the overseas brand name in China will undoubtedly lead to the natural emergence of a Chinese version of the brand name adopted by Chinese locals. This Chinese ‘orphan’ version of the original brand may not necessarily carry the connotations, or reflect the brand values, which the brand owner would prefer. This can, however, be the least of the brand owner’s problems. The even bigger risk for the brand owners is when a third party (frequently called a “trademark pirate”) registers the equivalent Chinese brand first. In this situation, the brand owner faces the threat of losing the Chinese brand and, worse still, being sued by the third party registrant for using it. This article focuses on two distinct but parallel instances where this can occur. The www.intellectualpropertymagazine.com first is with respect to a brand owned and promoted by a company and the second occurs in the unique situation where the brand name is a personal name which is synonymous with a famous person. Two recent cases are illustrative of these issues. Castel This is what happened in a case involving the prestigious French winemaker Castel. Castel entered the Chinese market using a Chinese equivalent of its Castel brand called ‘Ka Si Te’. The Ka Si Te brand soon acquired a reputation with the Chinese public. Crucially, Castel only registered the ‘Castel’ brand and not its Chinese equivalent, Ka Si Te. A Chinese party managed to register the Ka Si Te mark. Castel tried to cancel the pirate Ka Si Te mark but, after a cancellation dispute lasting six years which was appealed as far as the Supreme People’s Court, Castel failed. Castel was then sued by the Chinese registrant for using the Chinese Ka Si Te mark. The trader sued for infringement and for damages of up to $31m. Interestingly, during the course of the proceedings, in response to an application from the Chinese trader, the court applied a property preservation order on Castel’s ‘Caste’ trademark in China (ie a trademark which was, strictly, unrelated to the proceedings), meaning that the mark could not be licensed or assigned until the infringement case was resolved. The Castel trademark was, in effect, acting as ‘surety’ for any damages which Castel was required to pay in the event that the Chinese trader succeeded in the proceedings and May 2013 Castel did not comply with an order requiring it to pay damages. It is believed that this was the first time that a Chinese court had applied a property preservation order to an intangible asset. Castel was finally ordered to pay compensation to the Chinese party of RMB33.7m (around $5m). The primary lesson therefore is regardless of how famous and well-known a brand is elsewhere around the world, time should be taken to devise a Chinese language equivalent of a brand and that time and money should be spent in registering that brand. The decision is of particular note for foreign entities which do not have significant assets in China. Typically, such entities may have considered themselves insulated from the risk of litigation in China due to a lack of assets in the country. However, even foreign entities without significant assets in China very often have trademarks there. Those trademarks are now in the firing line if the foreign entity ever gets sued, whether for trademark infringement or for other causes of action, particularly where the foreign entity has limited assets in China. Michael Jordan After two decades on the basketball court, Michael Jordan, one the greatest basketball players of all time, is currently learning the rules of defence and offence in a different game: the Chinese legal system. Qiaodan Sports Company Limited (Qiaodan Sports), a Chinese sportswear company, is throwing its legal dispute with him back into his court. Intellectual Property magazine 63 Spotlight on Asia Michael Jordan’s fame in China is longstanding. He was first seen on Chinese television playing for the 1984 gold medal-winning US basketball team at the Los Angeles Olympics. Since then, he has become hugely famously in China, both under his English name but also under his Chinese name 乔丹 which is the Chinese equivalent of the name Jordan. This Chinese name is shown in pinyin, the official system which is used to transcribe Chinese characters into Latin script, as ‘Qiaodan’. While Michael Jordan registered trademarks for Jordan in English in China as far back as 1993, he never applied for any registered trademarks for 乔丹, nor for the pinyin representation Qiaodan. Qiaodan Sports first applied to register the name Qiaodan when it applied to use the name with the logo of a baseball player at bat. It also filed several trademark applications for 乔丹 and Qiaodan, which were approved for registration in 1998. Qiaodan Sports has been using its Qiaodan and 乔丹 brands since 2000 and has made significant brand-building efforts over the years. Qiaodan Sports currently owns about 6,000 shops in China which trade under its name. In November 2011, Qiaodan Sports won approval from the China Security Regulatory Commission for an IPO of 112.5m shares to raise about RMB1.1bn (approximately $178m). On 21 February 2012, just as Qiaodan Sports was set to debut on the stock market, Michael Jordan cried foul and commenced proceedings against Qiaodan Sports for the unauthorised use of his name at Shanghai No. 2 People’s Intermediate Court. He claimed that Qiaodan Sports was illegally using his Chinese name and his jersey number 23 on their products without his permission. Since Michael Jordan has never registered any trademarks for his Chinese name, his claim is based on the grounds that Qiaodan Sports’ use of his Chinese name was in breach of his rights in his Chinese name. He demanded that Qiaodan Sports stop using the name and the trademarks and requested compensation. While Chinese law generally protects parties who hold registrations and who file early for them, this does not mean that it is open season to register the names of famous people, even if they do not have registered trademarks. Specifically, Chinese law protects the right of personal names under Article 99 of 民法通则 (General Principle of Civil Law) and prohibits infringement of the naming rights of individuals under Article 2 of 侵权责任法 (Torts Liabilities Law). These principles are also reflected in Article 31 of 商标法 (Chinese Trademark Law) which provides that an individual’s name rights shall be protected as a prior legitimate right. In its defence, Qiaodan Sports contended that the Chinese name 乔丹 and its pinyin 64 Intellectual Property magazine representation Qiaodan were only a translation of the English word Jordan and that they were not Michael Jordan’s real name or full name. It noted that there were about 4,600 Chinese citizens with the name Qiaodan and even more foreigners that have translated their names to Qiaodan. As such, it argued that 乔丹 and Qiaodan should not belong exclusively to Michael Jordan. These proceedings were brought following recent decisions by the Chinese courts in favour of protecting the naming rights of other well-known basketball players such as Yao Ming in 2011 and Yi Jianlian in 2010. A Chinese court ruled for former NBA player, Yao Ming, who challenged Wuhan Yunhe Sharks Sportswear Company for using his name and the logo, Yao Ming Era, on its products. The company was forced to stop using the name and to pay RMB300,000 in damages. Another NBA player, Yi Jianlian, won against Fujian Yi Jianlian Sport Goods Company at a Chinese court which held that an individual’s name right should be recognised as a prior right. To slam dunk his naming rights claim, Michael Jordan will need to establish that: 1. He is a famous public figure and his fame under his Chinese name preceded Qiaodan Sports’ trademarks 2. Qiaodan Sports has acted in bad faith by intentionally using his Chinese name or other personal attributes without his permission 3. The use of his Chinese name or other personal attributes has injured him by causing confusion among consumers who misguidedly associate Qiaodan Sports or their products with him. The Shanghai court accepted this case on 1 March 2012, and there has not yet been any verdict so far. In an interesting twist to this case, on 26 March 2013, Qiaodan Sports threw the ball back into Michael Jordan’s court and countersued him for an apology and damages at the Quanzhou City Intermediate People’s Court in Fujian, alleging that the above lawsuit has tarnished its reputation and thwarted its plan for an IPO on the Shanghai stock exchange. The Fujian court accepted the case on 2 April 2013. Many sports companies in China have been looking to capitalise on the sudden popularity of NBA surprise standout Jeremy Lin by selling jerseys and t-shirts bearing his Chinese name, Lin Shuhao, or his English name. The Financial and Economic Committee of the National People’s Congress recognises that there are many businesses that register the names of celebrities as trademarks, affecting the rights and reputation of these celebrities and public May 2013 interests. Therefore, they have already made recommendations to the Legislative Affairs Office of the State Council for amendment to 商标法 (Trade Mark Law) in order to give additional protection to the naming rights of individuals. There are two practical consequences of these cases for overseas brand owners. Firstly, these cases highlight yet again the importance to overseas brand owners of ensuring that they adequately protect their brands in China. Failing to file trademark applications in China at the earliest possible date is a mistake which many overseas brand owners continue to make, despite the fact that China has clear and well-established rules giving preference to the party who is first to file. A prudent trademark protection strategy should involve (where necessary) devising and, just as importantly, filing to protect the Chinese language version of their mark. With respect to the particular situation of a foreign celebrity, he or she should not assume that their name rights necessarily extend to Chinese equivalents of their name, such as 乔丹 or the pinyin representation of the celebrity’s name such as Qiaodan. As well as registering their name in Latin characters, celebrities should, at an early stage, invest time and money in registering the Chinese equivalent of their name in order to avoid third parties in China from registering it before they do. Authors Edward Chatterton is a partner (foreign legal consultant) in the intellectual property and technology team based in Hong Kong. He specialises in intellectual property work, with a particular emphasis on providing litigation and transactional intellectual property advice. Ann Cheung is a trainee lawyer in DLA Piper’s intellectual property & technology group, based in Hong Kong. Cheung has experience in the sports, media and entertainment sector and has assisted on a number of high profile deals including structured finance work for Hollywood studios, litigation work for football organisations, the sales and purchasing of IP rights, the acquisition and disposal of broadcasting companies and joint ventures and advice on data protection laws and copyright assignments. www.intellectualpropertymagazine.com